Four Japanese Catholic nuns called. They had a small cake baked for us by their Mother Superior. The icing represented the Philippine and Japanese flags. One of the nuns apologized because they had been compelled to make the cake without sugar, butter, or baking powder. Another, who had been in the Philippines, wistfully rehearsed her scant Tagalog and afterward insisted on borrowing a new textbook, Tagalog-Nippongo, brought out a few months ago by one of the Filipinos in Japan. She talked cheerfully of going back to the Philippines which, it seemed, she had grown to love. How shall one make them understand that no Japanese will ever be able to step on Filipino soil for the next generation without running the risk of being torn limb from limb?

Eddie Vargas returned to Tokyo today. All civilian communications to the Philippines have been suspended. When he landed in Taiwan, he said, the airport was still littered with the wreckage of about 70 planes. The planes taking off for the Philippines the next three days had been all shot down and finally he had been forced to give up the trip. On Taiwan he had been constantly shadowed by kempei. He was frisked once after coming from church. One particular kempei, apparently because he did not know anything else in English, kept asking his name. He barely resisted the temptation of giving a different one every time. The kempei in Fukuoka on the mainland proved to be more amenable. Eddie gave him some Taiwan candy every time he wanted to ask questions.

One of our students in Japan, a former guerrilla in the Philippines, shared some of his experiences with me when he called. One youngster in his outfit had cold-bloodedly shot down a town treasurer, in full view of his daughters, purely because the man was making himself unpleasant by too much whining on the way to their hideout where he was wanted for questioning. Another, after a raid on an occupied town, wanted to go back because he had not had a chance to kill his first man. A third, who used to go hunting cows with a heavy machine-gun, finally ended up by betting his coming bonus on the possibility that his revolver, after the half-loaded roller had been twirled, would not go off. He put the gun to his head and it did go off. The young are bloodthirsty, I thought. Possibly they do not know the value of human life.

It was the same student who told me with some relish that since the total blackouts began to be enforced, increasing numbers of women had been found dead in the sidewalk shelters in Tokyo and Yokohama. They had been raped and robbed. When he told me about it, I could not tell whether he was happy because they were Japanese or shocked because they were women. His eyes would fill and deepen and then a teasing, calculating smile would light up his smooth unlined baby’s face.

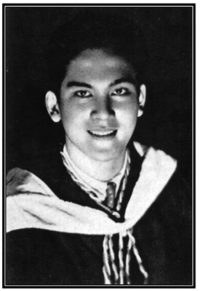

I have often wondered about Danny. He was in his teens when the war broke out (I think he still is). His father, whom he loves and respects more than any other man, works with the Japanese; he went out to kill them. They did it for the same reason; the independence of our country and the welfare of our people. Was one right and the other wrong; must one and one alone be right and other wrong; or are these shining phrases mere words, habitual disguises for the individual instinct and choice?

Danny was caught, thrown into a dungeon, tortured perhaps, then released on an amnesty (it was the emperor’s birthday). Then he came to Japan as a government scholar. Why? I have never asked him. But I have gathered from loose ends in our conversations and from the stories of his friends, that he wanted to “give the Japs a chance”. Perhaps they meant what they said; perhaps they had something worth learning and working over: a code of honor (even before the war bushido was a good word in the Philippines), the ideal of Pan-Asianism (Asia for the Asiatics, the Philippines for the Filipinos).

But it hasn’t worked out. Danny is too much of an American or too much of a Filipino or too much of both. He thinks in English (although he never could spell), he loves the boogie, he is used to asking questions and getting answers instead of a slap in the face. He hasn’t touched his books in Japan; he wanted to study architecture and they put him in an engineering school; he says he will not be “broken” by the drill sergeants who pass themselves off as teachers.

Now he spends his days making love to Niseis, collecting “military information” for future use, writing poetry, not love poetry as one would expect but “native land” poetry and “peace” poetry and “humanity” poetry in the vein of the “brotherhood of man”. For he has not forsworn Orientalism; he has cut it up and spread it out; he talks of the U.S.S.P., the United States of the Southwest Pacific, and of the “Sepia Federation” which will unite all the Malays; he talks also of writing a book on peace and how it can be found and kept.

One can see that he is no longer bloodthirsty; he can afford to talk tolerantly when he tells his stories of guerrilla murders and raids. He no longer hates the Japanese; he has lived here too long. He only despises them with a contempt that is softened with pity; “These people are crazy. They don’t know what’s good for them. But by God, a few more bombs will l’arn them.” What will his comrades in the guerrilla bands think of him now? Will they think he has gone soft, that he has betrayed them, that he has gone over to the enemy? Or will there be one among them who will comprehend something of the tortured indecision that eats at the secret heart and shakes the brooding soul of every man cursed with understanding, tolerance, and a sense of the kinship of all men?