Almost unnoticed amid the mourning for Tokyo was the first faint death-rattle of Okinawa. On the night of the 24th the Giretsu air-borne unit of the special attack corps (Giretsu means heroism) clambered into the black bellies of a squadron of transport planes to spearhead a a Japanese general counter-offensive on Okinawa. Almost two months had passed in blood and fire since the first American landings. Now the Japanese garrison was making its last stand on the jagged line between Shuri and Maha. The special attack corps, in spite of suicide pilots riding rocket bombs, had failed to smash the American line of communications. Carrier-borne fighters were again scouring southern Kyushu and the press was wandering uneasily whether the Americans were planning another landing.

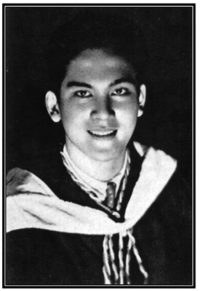

Perhaps the men of the Giretsu knew they were playing Japan’s last card. It had been played before the end of the game in Leyte. Could it win the trick this time? They had fought together from Peliliu to Okinawa, under their “boy-commander”, 26-year old Captain Michiro Okuyama, sleeping in their uniforms, running instead of walking in their daily life to accustom themselves to unrelenting speed.

Tonight a high wind from China has pushed away into the sea the black clouds that hung low over Okinawa. The sky was radiant with moonlight. In silence they heard the last “address of instructions”; the divine Tenno had “granted gracious words, placing great hope in the operations” and they were notified of the “gracious imperial concern”. In “uniforms camouflaged with green dots and streaks” they took their places. Each of them carried hand-mines and 10 off “crack new weapons” as well as special iron rations. They were the last hope of the empire.

At 9 a.m. the next morning, the 25th May, they sent the reassuring message. “Have succeeded in landing.” Bad weather had returned. An observation plane, skimming the leaping waves, its windshield blurred with rain, reported that the Giretsu were holding off repeated American attacks while wrecking and blasting planes and dumps on the north and central airfields on Okinawa, “throwing the enemy into confusion”.

Meantime, “less than an hour after the divine soldiers had landed on the north and central airfields, special attack units and other air units sank (some instantaneously) two aircraft carriers, four battleships, one cruiser, one destroyer, four large transports and four aircraft of unidentified category.” No official announcement has been made but it presumed that the land forces on Okinawa have also launched a general counter-attack.

[illegible] the 27th the vernaculars noted briefly that it that it was [illegible], the 40th anniversary of the battle of the Japan Sea. But there was no Togo on Okinawa and there was no imperial fleet “in this same sea zone”. It was now Japan’s turn to fight against hopeless odds and to make the tragic discovery that the time had long since passed for the daring and gallant raid that could turn defeat into victory.

A consciousness of this seems to have seeped into the Japanese mind. For the past four days the English edition of the Mainichi has been running a biography of a modern naval hero, Vice-Admiral Masabumi Arima, who personally led his squadron in a suicide attack in the Philippine waters on the 15th October 1944. Significantly Japan’s new hero is a suicide, not a conqueror; his message is duty to the death, not victory.