The General has gone to the City Government Building as Provost Marshal-General, and has not yet taken me from here. The first day I moved the office up to the second floor. Here we have two grand rooms—one large and the other rather smaller; the latter is my private property. The ceiling must be quite twenty feet high, and the windows and doors match. At night I find we get all the breeze there is, and no more than our share of the mosquitoes. The General said, this morning, that he had more work than he could see his way through, and that he should want me to come down to his present headquarters in a day or two, but that, in any case, he would keep the office here in the palace for a sleeping-place for me. He also remarked that he was looking for a saddle horse, and “when I get it I shall probably want you to exercise it more or less.” He is so kind to me that I hardly feel as if it were the part of a soldier to be his messenger, but still I am glad to be. I shall be well satisfied to be connected with this municipal administration as the governing problem is more pressing here now than the military, and I rather think that the General will have to take the brunt of the former in his position. He has three regiments—the Twenty-third Infantry, the Thirteenth Minnesota, and the Second Oregon Volunteer Infantry—as his police force. In addition to the police work, he is responsible for the water, electric light, fire, street-cleaning, and penitentiary departments of the city. I had a little share in the street-cleaning question the other day. It was before the General was formally appointed. He wanted to know about how many carts and men the Government had, and where these carts were. I brought the subject up when I was talking with my Spanish friend at his house. I found that a gentleman in the same house had been in the city government, and I learned from him the system of their street-cleaning. It is done by contract, the government furnishing transportation. I was able to make a somewhat full report the next morning to the General—the information being what he wanted, and what he had. not been able to get hold of. I had been able to get the name and address of the contractor. I heard him to-day, in talking with a Major who has been put in charge of street-cleaning, use the material I was so lucky as to chance upon. The Spaniards are very nasty in trying to block the administration in a thousand little ways, and they are the hardest people to get information out of, if you go at it directly. There would be good use here for a secret service of five or six efficient men. The General is persuaded that there are large amounts of Government property stored away in churches and private houses in the city which should be searched out and claimed by the United States. One instance of the way they waft away the stuff: when the officers went to take charge of the Spanish public treasury, the grand Archbishop comes along and says it is his—has been loaned to him, and therefore, being church property, it is “hands off” for the Americans. The way the matter was settled I know not. Under the circumstances I should have been tempted to give the Archbishop just about thirty seconds to give up his money, á la good old Western style. I must tell you a story I heard of the times here before the battle, when the Germans were threatening trouble. You very likely have heard it, but it is so good, and also reported as authentic, that I will run the chance of repeating. The German admiral, it seems, went to the British admiral and asked him what course he would take in case the Germans should take part with the Spaniards at the storming of the city — in short, if the German men-of-war should attack the American fleet. The English admiral replied, with perfect graciousness: “Only Admiral Dewey and myself know what I should do under those circumstances.” It was enough to silence the German.

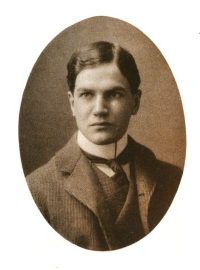

E. Huntington Blatchford

(October 9, 1876 — December 23, 1905). In 1898 he enlisted in the United States Cavalry and was stationed in Manila where he remained for six months.

All Posts