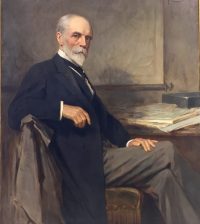

Church in the morning with a little drive afterwards. Long chat in the afternoon with Judge Day about the prospects of the conference. He is nearly over his illness, though still weak. I gave him the results of various reports reaching me from Paris, Madrid and elsewhere to the effect that the Spanish Commissioners were talking about breaking off. While we were considering the probability of this, Beriah Wilkins, proprietor of the Washington Post, came in. He had spent some time this afternoon at the headquarters of the Spanish Commissioners talking with Ojeda, to [whom] the others referred him, and having a little conversation also with some of the Spanish Commissioners themselves. He described them as bitter, resentful, and above all not willing to make themselves martyrs by signing a treaty which would ruin them at home….

Dinner in the evening at Sir Campbell Clarke’s and fine amateur music afterwards. The German Ambassador, our own, and the German military attaché almost the only guests. . . . Count Münster evinced a great curiosity to know the present status of our negotiations and said:

“The Spaniards will not give up the Philippines. Do you still insist upon them, or will you waive that?” When I told him that the attitude of the United States on this subject would be uncompromising, he said: “Well then they won’t sign the treaty. You may be sure of it, they are not going to sign.” This in various phrases he repeated several times. His idea, as I gathered it, was that none of the Spanish Commissioners were willing to make martyrs of themselves at home for the sake of getting a treaty. He seemed to think that we would thereupon immediately take possession of the whole group, but said: “You will have a hard nut to crack.” I explained how without the remotest intention originally of acquiring territory in that quarter, we had been forced into the attack on the Spanish fleet at Manila, and had become responsible for the present situation there. He seemed to agree with me that we could not honorably turn over again to Spain the government over a region where we had broken her rule down. I then dwelt on the difficulty of making any other disposition of the Islands. [I pointed] out that if we gave them to England or Japan, or Russia, or any other power, we were immediately provoking international difficulties. He rather assented to the proposition that the best thing possible for all concerned was that the United States should retain them. [He] repeated, however: “You will find it a hard nut to crack. We don’t want them, however,” he repeated, “and my government doesn’t.”. . .