About the author: Natalie Corona Stark Crouter (October 30, 1898 — October 15, 1985).

About the author: Natalie Corona Stark Crouter (October 30, 1898 — October 15, 1985).

From the Papers of the Stark Family section in the Arthur and Elizabeth Schlesinger Library on the History of Women in America, Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study, Harvard University, comes the following information:

Natalie Corona (Stark) Crouter was born on October 30, 1898, in Dorchester, Massachusetts. She survived a bout of meningitis and polio at age nine, and was left with a weakened left leg. She attended Dorchester public schools, the Deverell School (New York), the Burnham School (Northampton, Massachusetts), and Katherine Gibbs Secretarial School (Boston, Massachusetts). She used her secretarial skills in the Sacco and Vanzetti defense effort. In 1925, she met Errol Edgerton Crouter in the Philippines where she was forced to stop during a world tour with her father due to her father’s illness. They were married on February 3, 1927, in Tientsin, China, and settled in Vigan and later Baguio in the Philippines.

Errol Edgerton Crouter, whose nickname “Jerry” was inspired by Jack London’s Jerry of the Islands, was born on April 11, 1893, in Greeley, Colorado. The son of Charles, a pharmacist, and Mabel (Maltby) Crouter, he became a lawyer but disliked legal work so he enlisted in the Army and was stationed in the Philippines where he remained following his discharge in 1918. He was a recruiter of Filipino workers for the Hawaiian Sugar Planters’ Association before the organization closed during the Depression. He then became an insurance salesman and managed a Shell gas station. Natalie and Jerry had two children, June (b.1929) and Frederick (b.1931). The entire family was interned by the Japanese Army during World War II. Following the war, the family stayed with Bertha and Mary Ethel Stark in Dorchester, Massachusetts, before moving in with Marguerite (Stark) Bellamy in Cleveland, Ohio. Jerry moved back to the Philippines as an employee of the United States War Shipping Administration and suffered a massive stroke in August 1946. He then returned to Cleveland where he was sporadically employed by the Veterans’ Administration and several private businesses. June graduated from Western Reserve University and received her master’s degree in social administration from Western Reserve’s School of Applied Social Science. She married Richard Wortman in 1967; they had two children, Rebecca and Glen. Frederick graduated from Mather College and received his M.A. in education from Montclair State College. He married Louise “Lou” Patterson in 1953; they had three children (Jerrol, Jennifer, and Lenore). Jerry died in 1951 of cirrhosis and cancer of the liver; Natalie died October 15, 1985.

American Heritage, in an article that contained an extensive extract from the book, had the following:

The Crouters—Natalie, her husband Jerry, an American who had an insurance business in the Philippines, and their two children, June, aged twelve, and Bede (Fred), aged ten—were luckier than many Americans interned by the Japanese during World War II. For most of their imprisonment, they were at Camp Holmes, a place of great beauty and clean, healthy air, high in the mountains of Luzon, where the internees were allowed to govern themselves within set limits. At first, food was not a critical problem. With gifts from the outside, and what money they had managed to hang on to, the internees were able to supplement the camp diet. But crowding, lack of privacy, and perverse social regulations were onerous. For instance, “commingling” was forbidden. Although families could eat and visit together, men and women were housed separately.

There are more interesting details that can be gleaned from the description of the contents of the Stark Family papers page in the Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study, Harvard University website:

Series IV, NATALIE STARK CROUTER AND FAMILY, 1891-1985 (#38.7-87.12, 97FB.5-100FB.4, OD.1, SD.1), includes correspondence, diaries, scrapbooks, appointment books, etc. It is arranged in four subseries.Subseries A, Biographical and personal, 1891-1977 (#38.7-48.9, 97FB.5-97FB.6, 98FB.1-100FB.4, OD.1, SD.1), contains appointment books, diaries, scrapbooks, financial documents, etc. Materials document Natalie’s attendance at Camp Winnetaska in Ashland, New Hampshire, as well as her education in Dorchester (Massachusetts) public schools, the Deverell School (New York), the Burnham School (Northampton, Massachusetts), and Boston University. Also documented are Natalie’s liberal political views and her involvement in liberal groups and causes. Financial documents detail the Crouter family’s financial status, Natalie’s application for financial assistance from the government for Jerry’s healthcare costs, and the Crouter’s efforts to receive financial compensation from the government for their internment during World War II. From the 1950s through the 1970s, Natalie travelled to Europe, Africa, and China. Her trips are documented through itineraries, correspondence with travel agencies, diaries, and memoirs she wrote upon returning. Folders are arranged alphabetically.Subseries B, Family correspondence, 1899-1978 (#48.10-55.12), contains letters from Natalie’s family and carbons of her letters to them. They include news of family and friends, accounts of local events, opinions on national and world events, accounts of books read, and critiques of movies and plays. Letters from Errol Edgerton Crouter (1945-1947) recount his return to the Philippines, including the unsettled political situation, damages from the war, and news of friends who were in the Philippines. Letters continue through the period immediately following his stroke and document Jerry’s confused state of mind and his medical treatment. Folders are arranged alphabetically.Subseries C, Friends and other family correspondence, 1900-1985 (#56.1-77.7), contains correspondence between Natalie and other family members and friends. Letters from 1917 and 1918 document Natalie’s patriotic support of World War I, and include letters from soldiers fighting in the war.Correspondence from the 1920s document Natalie’s support of liberal causes in the Boston area, including the defense of Sacco and Vanzetti. The 1920s letters also include some from several of Natalie’s suitors, who often continued to write after the courtship ended. Letters from the 1930s and early 1940s document Natalie’s life in the Philippines, particularly her involvement in Indusco, the fundraising arm of the Chinese Industrial Cooperatives, which organized cooperative factories throughout China. Post-World War II correspondence includes letters from fellow internees detailing their lives, usually in the United States. Several letters from the same correspondents were found bundled together when the collection arrived at the library. These groupings were retained by the archivist, and other letters from the same correspondents were added. They are listed by correspondent and can be found at the end of the subseries. Folders of general correspondence are arranged chronologically.

About the diary: From the same American Heritage article:

About the diary: From the same American Heritage article:

On December 5, 1941, Natalie Crouler, an American housewife living in the Philippines, started a chatty letter to her mother in Boston…

Natalie ‘s aborted letter to her mother turned into a diary that she kept daily throughout the mounting hardships of their internment. To keep such a record—her notes, she called it—was an offense punishable by death, but she persisted, convinced that the diary was preserving her sanity. She wrote in a microscopic script on small scraps of paper—flaps of envelopes, margins of book pages—then wrapped bundles of her scraps in plastic cut from an old raincoat, and hid them in the family food supplies, once coating them in butter, at other times burying them in sugar or beans. The diary became her most precious possession.

There are more details in the Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study, Harvard University page on the Stark family papers:

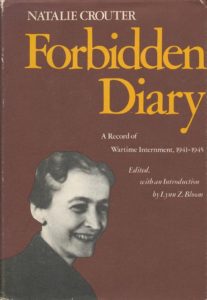

Subseries D, Philippines internment and related, 1941-1946, 1973, ca.1980 (#77.8-87.12, 97FB.7), includes four versions of the diary Natalie kept during her internment. Because keeping a diary was an act punishable by death, Natalie wrote the diary on small pieces of paper which she wrapped in plastic and hid among the food supply. After the war, the United States government seized the diary. When it was returned, Natalie transcribed it and added more details. In the 1970s, she began to work with Lynn Z. Bloom to produce a version for publication. It was published in 1980 as Forbidden Diary: A Record of Wartime Internment, 1941-1945. While it is clear that the version labeled “original” is the first version, the other versions found here were labeled 2nd, 3rd, and 4th version by the archivist as a means to indicate their development; other versions may have existed but were not included in the collection. Only a fraction of the diary was published. Omitted portions contain additional information on life in the camp: food consumed, the division of work, her frustration with the situation and people, etc. This series also includes notes, mementos, forms, etc., relating to the Crouter’s internment and from the period immediately following their release. Also included is a certificate from the Ohio House of Representatives recognizing the publication of the diary. Diary folders are followed by a chronological arrangement of related materials.

Published as Forbidden Diary: A Record of Wartime Internment, 1941-1945, by Natalie Crouter. New York: Franklin, 1980. The same American Heritage article reveals the story of how the diary ended up published:

Both its survival and quality are astonishing. Natalie Crouler was not a professional writer, but writing entirely for herself, her children, and the children she hoped they’d have, she left an unforgettable record—vivid, honest, and compassionate—of what life was like in an internment camp, for captives and captors alike. Edited by Lynn Z. Bloom, The Internment Diary of Natalie Crouter , from which the following article is excerpted, will be published by Burt Franklin & Company. This book is the second volume of their American Women’s Diary Series.

The Roderick Hall Collection entry on the book says,

Crouter began her diary a few days before the war, sensing impending change, in the form of a letter to her mother. She never sent the letter and wrote in various scraps of paper. When the war broke out, the Crouters did all they could to prepare for the emergency, witnessed the bombings of Camp John Hay and then were interned by the victorious Japanese at Camp Holmes (now Camp Dangwa). She documents their day-to-day existence in the camp, her observations of the Japanese and on living conditions; their transfer through Luzon to Bilibid Prison in Manila in late 1944, and the joy of liberation in February 1945. She continues writing until July 1945, by which time she was too ill to write. Drawings by fellow-internee Daphne Bird bring visual images to Crouter’s words.

The entries originally reproduced in The Philippine Diary Project come from the American Heritage article, which is freely available online, and which was originally published as publicity for the book. The Project aims to contain all the published entries in time. While out of print, readers are encouraged to try to obtain a copy of the published version of the complete diary.