(entry updated January 25, 2016)

The beginning of World War 2, despite the immediate setback represented by Pearl Harbor, was greeted with optimism and a sense of common cause between Americans and Filipinos. See: Telegram from President Quezon to President Roosevelt, December 9, 1941 and Telegram of President Roosevelt to President Quezon, December 11, 1941.

However, From late January to mid-February, 1942, the Commonwealth War Cabinet undertook a great debate on whether to propose the Philippines’ withdrawing from the war, in the hope of neutralizing the country.

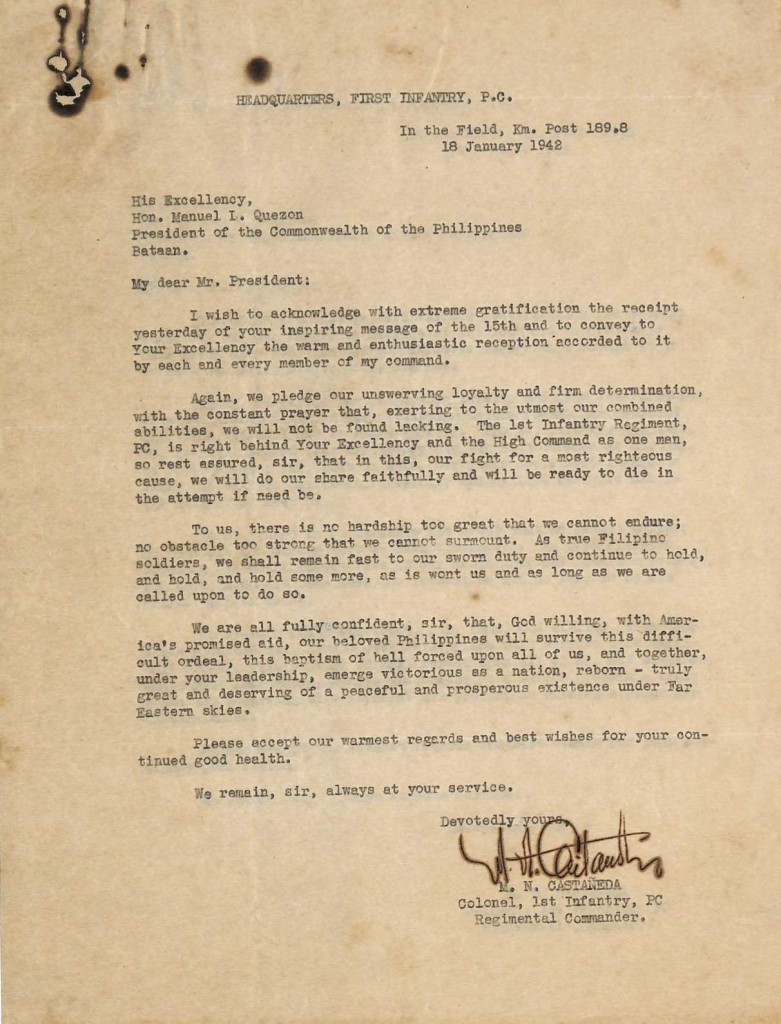

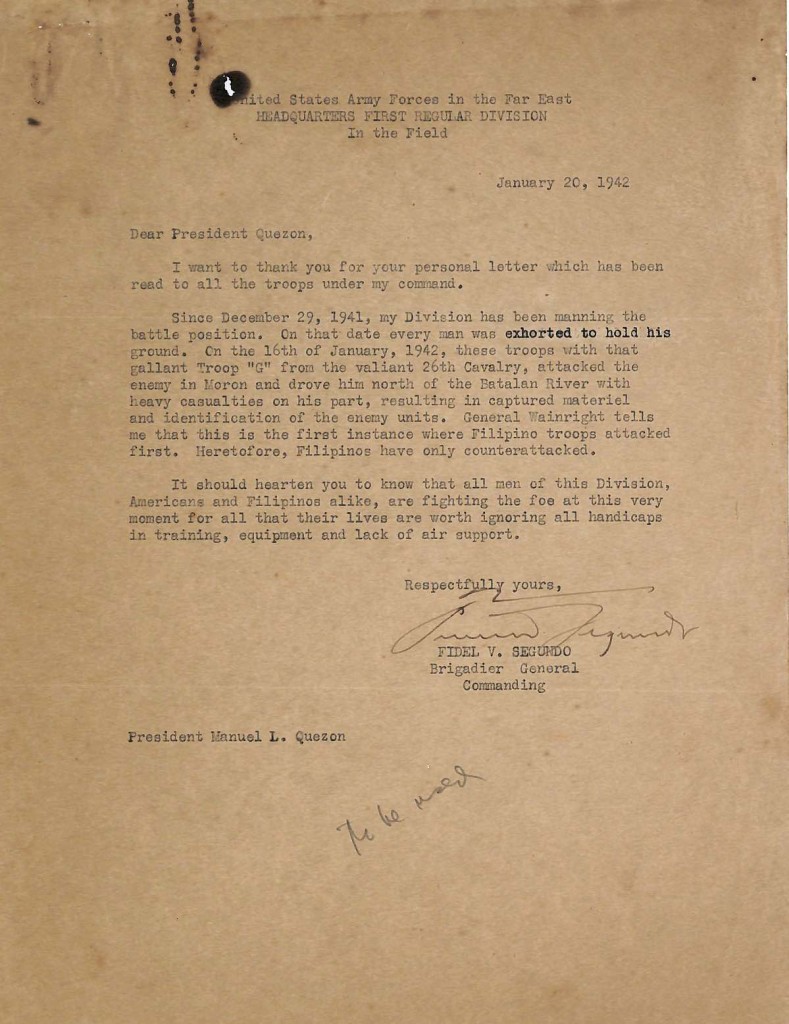

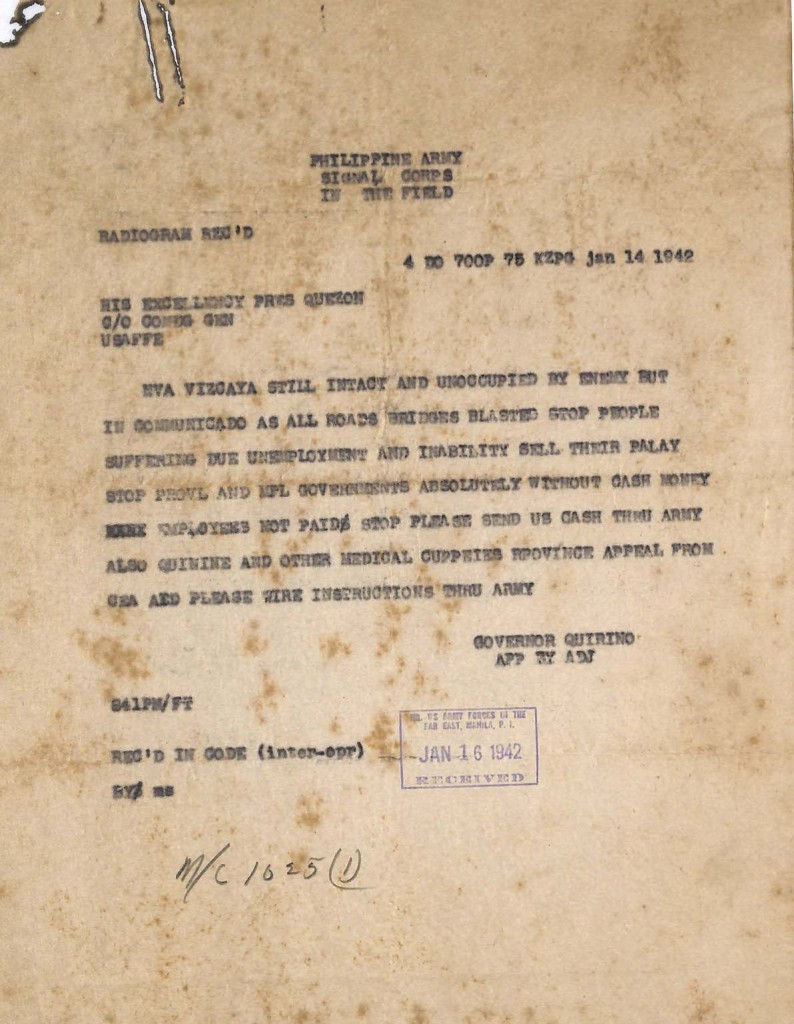

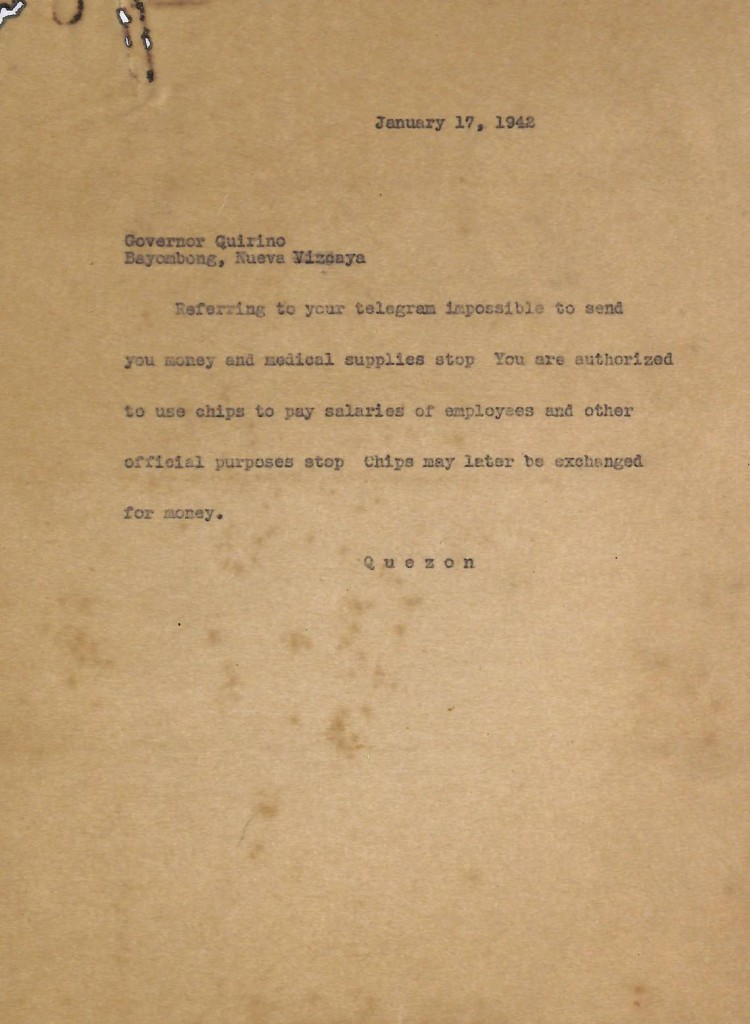

The cause of the debate seems to have been concerns over reports of the situation in the provinces, the creation of a Japanese-backed government in Manila, and the apparent lack of any tangible assistance to the Philippines as Filipino and American troops were besieged in Bataan. Here is a sampling of some letters received in Corregidor, from Filipino commanders at the front:

In his diary entry for January 21, 1942, Felipe Buencamino III, in the Intelligence Service in Bataan, visited Corregidor and wrote,

President Manuel Quezon is sick again. He coughed many times while I talked to him. He was in bed when I submitted report of the General regarding political movements in Manila. He did not read it. The President looked pale. Marked change in his countenance since I last had breakfast with his family. The damp air of the tunnel and the poor food in Corregidor were evidently straining his health. He asked me about conditions in Bataan –food, health of boys, intensity of fighting. He was thinking of the hardships being endured by the men in Bataan. He also said he heard reports that some sort of friction exists between Filipinos and American. “How true is that?” The President’s room was just a make-shift affair of six-by-five meters in one of the corridors of the tunnel. He was sharing discomfort of the troops in Corregidor.

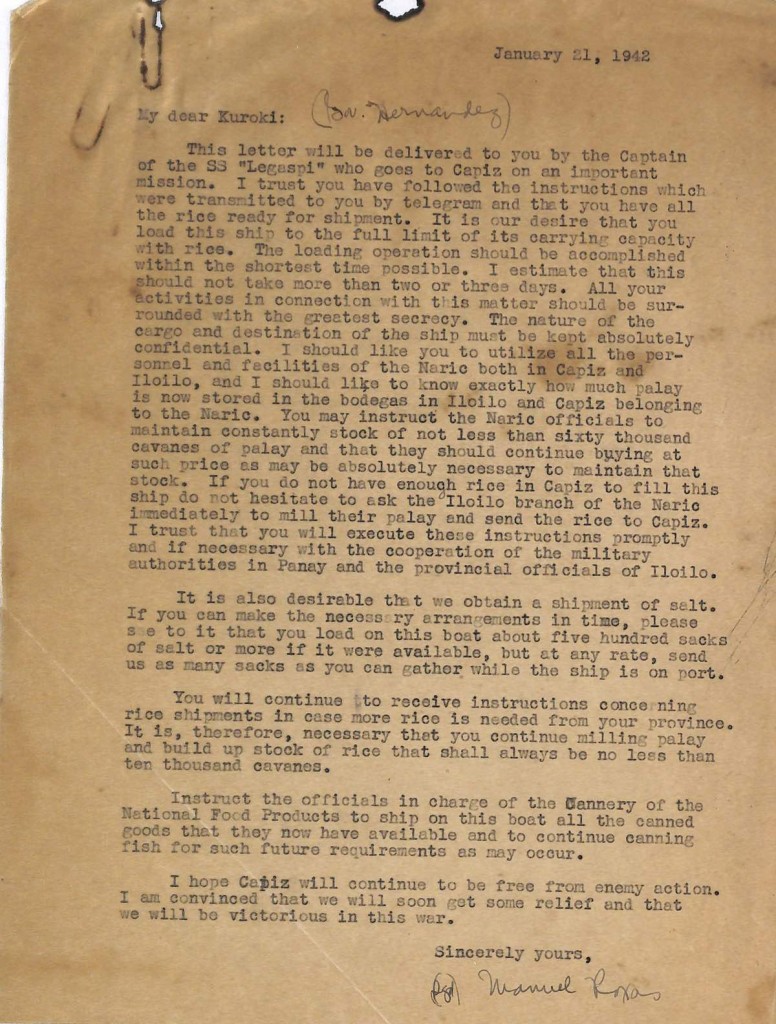

The hardships of Filipino soldiers in Bataan –young ROTC cadets had already been turned away when they turned up in recruiting stations in December, 1941, and told to go home (though quite a few would join the retreating USAFFE forces anyway)– was troubling the leadership of the Commonwealth. The troops, too, were beginning to starve. On the same day Buencamino wrote his diary entry, the S.S. Legazpi was dispatched to Capiz Province to try to bring rice to supply the troops:

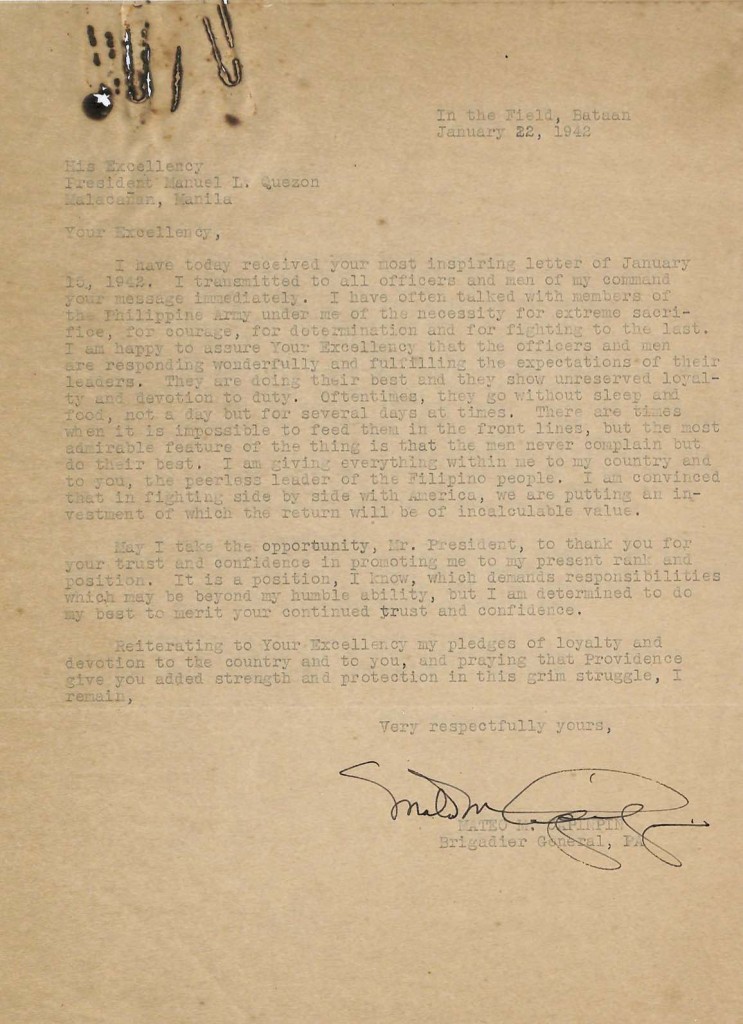

The next day, this letter would arrive from Mateo Capinpin, stating the lack of food for the troops:

On January 27, 1942, Felipe Buencamino III wrote in his diary,

Bad news: Japs have penetrated Mt. Natib through center of line of 1st regular division. Boys of 1st regular are in wild retreat. Many of them are given up for lost.

If this penetration widens, entire USAFFE line must fall back on reserve lines –the Pilar-Bagac road. This is our darkest hour. I’m praying for the convoy. Come on America!

The next day, January 28, 1942, Buencamino was writing in his diary:

Gap in western sector widening. Japs penetrating Segundo’s line in force. 1st regular division in wild retreat. Hell has broken loose in this area. Many dying, dead.

No reinforcements can be sent to bridge gap. No more reserves. 1st regular given up for lost. Japs following successes slowly, surely, cautiously.

USAFFE line will be shortened to stabilize and consolidate front. All divisions packing up to make last stand on Pilar-Bagac road. If this line, if this last front line breaks, our days are numbered.

Went to eastern front to see conditions there. Everybody is moving, retreating, to avoid being outflanked.

On that same day, the opening salvo in the debate over whether to keep the Philippines in the war or not was launched. Letter of President Quezon to Field Marshal MacArthur, January 28, 1942:

At the same time I am going to open my mind and my heart to you without attempting to hide anything. We are before the bar of history and God only knows if this is the last time that my voice will be heard before going to my grave. My loyalty and the loyalty of the Filipino people to America have been proven beyond question. Now we are fighting by her side under your command, despite overwhelming odds. But, it seems to me questionable whether any government has the right to demand loyalty from its citizens beyond its willingness or ability to render actual protection. This war is not of our making. Those that had dictated the policies of the United States could not have failed to see that this is the weakest point in American territory. From the beginning, they should have tried to build up our defenses. As soon as the prospects looked bad to me, I telegraphed President Roosevelt requesting him to include the Philippines in the American defense program. I was given no satisfactory answer. When I tried to do something to accelerate our defense preparations, I was stopped from doing it. Despite all this we never hesitated for a moment in our stand. We decided to fight by your side and we have done the best we could and we are still doing as much as could be expected from us under the circumstances. But how long are we going to be left alone? Has it already been decided in Washington that the Philippine front is of no importance as far as the final result of the war is concerned and that, therefore, no help can be expected here in the immediate future, or at least before our power of resistance is exhausted? If so, I want to know it, because I have my own responsibility to my countrymen whom, as President of the Commonwealth, I have led into a complete war effort. I am greatly concerned as well regarding the soldiers I have called to the colors and who are now manning the firing line. I want to decide in my own mind whether there is justification in allowing all these men to be killed, when for the final outcome of the war the shedding of their blood may be wholly unnecessary. It seems that Washington does not fully realize our situation nor the feelings which the apparent neglect of our safety and welfare have engendered in the hearts of the people here.

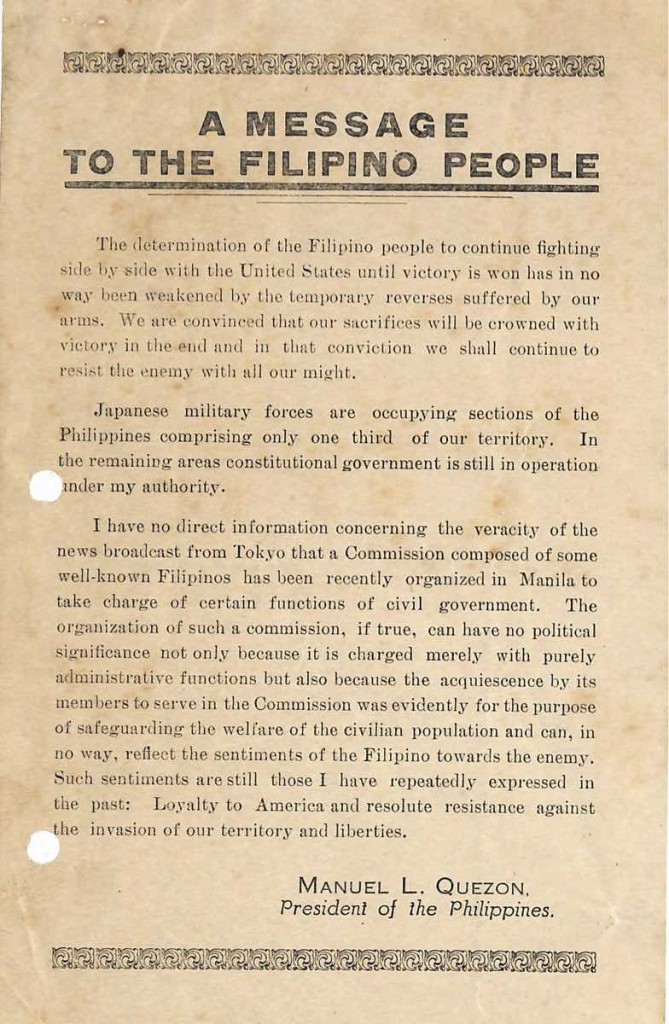

In the same letter, Quezon asked that a proclamation be given the widest possible publicity. Here it is in leaflet version, distributed in the front lines:

The next day, January 29, 1942, Buencamino would write,

Japs have encircled the 1st regular. I wonder what will happen to the boys there. This is a great calamity.

Apparently, Japs crawled through precipices of Mt. Natib. After penetration, they made a flank maneuver and concentrated fire on rear of Segundo’s line.

MacArthur forwarded this letter to President Roosevelt in Washington, and according to most accounts it triggered unease among American officials. See Telegram from President Roosevelt to President Quezon regarding his letter to Field Marshal MacArthur, January 30, 1942:

I have read with complete understanding your letter to General MacArthur. I realize the depth and sincerity of your sentiments with respect to your inescapable duties to your own people and I assure you that I would be the last to demand of you and them any sacrifice which I considered hopeless in the furtherance of the cause for which we are all striving. I want, however, to state with all possible emphasis that the magnificent resistance of the defenders of Bataan is contributing definitely toward assuring the completeness of our final victory in the Far East.

The day after FDR sent his telegram, the front in Bataan stabilized, as Buencamino recorded in his diary on January 31, 1942:

Good news. Troops of Segundo have reentered our new lines. They escaped Jap encirclement by clambering precipices on Western coast for two days and nights. The men looked thin, haggard, half-dead. They all have a new life. Segundo arrived with troops dressed in a private’s uniform. Japs were slow following initial successes. Some boys, unfortunately, fell while clambering through very steep precipices. In some cases, men were stepping in ledge only half-foot wide. Some of the wounded were left to mercy of Japs. Others were carried by companions. I will try to see either Feling Torres or Manny Colayco. They belong to the 1st Regular –if they are still alive.

There seems to be a move to change Gen. Segundo. Col. Berry will replace him, I understand. I don’t think Segundo is at fault. His troops have been fighting since December in Camarines. His men are recruits, volunteers, mostly untrained civilians. His division has not had a bit of rest since campaign in Southern front and when Japs first attacked Bataan front, they chose his sector.

The Philippine Diary Project provides a glimpse into how the telegram from FDR was received. On February 1, 1942, Ramon A. Alcaraz, captain of a Q-Boat, wrote,

Later, I proceeded to the Lateral of the Quezon Family to deliver Maj. Rueda’s pancit molo. Mrs. Quezon was delighted saying it is the favorite soup of her husband. Mrs. Quezon brought me before the Pres. who was with Col. Charles Willoughby G-2. After thanking me for the pancit molo, Quezon resumed his talk with G-2. He seemed upset that no reinforcement was coming. I heard him say that America is giving more priority to England and Europe, reason we have no reinforcement. “Puñeta”, he exclaimed, “how typically American to writhe in anguish over a distant cousin (England) while a daughter (Philippines) is being raped in the backroom”.

The remark quoted above is found in quite a few other books; inactivity and ill-health seemed to be taking its toll on the morale of government officials, while the reality was the Visayas and Mindanao were still unoccupied by the enemy. Furthermore, Corregidor remained in touch with unoccupied areas, and a sample of reports and replies helps put in context the attitude of the Filipino leadership in Corregidor.

On February 2, 1942, Gen. Valdes wrote that the idea of evacuating the Commonwealth Government from Corregidor was raised –in case “forces in Bataan were pushed back by the enemy,” suggesting that holding the line after the last attempted advance by the Japanese still left the weakened defenders uneasy.

Writing in his diary on February 2, 1942, Felipe Buencamino III recounts battle stories of his comrades, and the physical and mental condition of soldiers like himself:

Talked to Tony Perez this morning about penetration in Mt. Natib. He said they walked for two days and nights without stop, clambering cliffs, clinging to vines at times to keep their body steady, in a desperate effort to escape encirclement by the Japs. He said it was a pity some of the weak and wounded were left behind. There were men he said offering all their money to soldiers to “please carry me because I can no longer walk.” He said that he and a friend carried a fellow who had a bullet wound in the leg. “Some of the boys” he said “fell down the precipice because the path was very narrow, in some cases just enough for the toes.” He expressed the opinion that if Japs had followed their gains immediately and emplaced a machine gun near the cliff, they would all have been killed. “It was heart-breaking” he said. “There we were trying to run away from Japs and sometimes we had to stay in the same place for a long time because the cliffs were very irregular, at times flat, at times perpendicular.” He said that most of the men discarded their rifles and revolvers to reduce their load. Most of our artillery pieces were left, he stated. “We were happy,” he recounted, “when night came because it was dark and the Japs would have less chances of spotting us but then that made our climbing doubly difficult because it was hard to see where one was stepping especially when the moon hid behind the clouds.” He opined that the Japs probably never thought that one whole division would be able to escape through those precipices in the same way that we never thought that they would be able to pass through the steep cliffs of Mt. Natib. Fred said he will write a poem entitled “The Cliffs of Bagao” in honor of the Dunkirk-like retreat of the 1st regular division…

Life here is getting harder and harder. I noticed everybody is getting more and more irritable. Nerves, I think. Food is terribly short. Just two handfuls of rice in the morning and the same amount at night with a dash of sardines. Nine out of ten men have malaria. When you get the shivers, you geel like you have ice in your blood. Bombing has become more intensified and more frequent. The General is always hot-headed. Fred and Leonie are often arguing heatedly. Montserrat and Javallera are sore at each other. And I… well, I wanna go home.

Another incident seems to have have happened the day after purely by chance, see Evacuation of the Gold Reserves of the Commonwealth, February 3, 1942. This mission was one of several intrepid efforts by American submarines. See Attempts to Supply The Philippines by Sea: 1942 by Charles Dana Gibson and E. Kay Gibson:

Although the U.S. Navy never showed any willingness to use its surface ships to assist the supply of the Philippines, whether for the carriage of cargo or as escorts, that reluctance did not apply to its submarines, but it took direct pressure from the White House to get action. Between mid-January and 3 May, eight U.S. submarines unloaded cargoes at Corregidor. For their return trips, they evacuated a total of 185 personnel together with the treasury of the Philippines as well as vital Army records. The quantity of the cargoes the subs delivered totaled 53 tons of foodstuffs along with various quantities of munitions and diesel oil. In aggregate, this was hardly enough to make a dent in the overall need; nevertheless, it was an asset to the morale of the defenders. The personnel who the submarines evacuated were of considerable import as most of them were essential to the future conduct of the war.

The same paper also discusses efforts to bring much-needed food and supplies to the soldiers in Bataan and Corregidor:

There was, though, one shining moment, and this was the result of a plan put in force by MacArthur’s quartermasters during early January to utilize ships which had been anchored off Corregidor since the evacuation from Manila in late December. Three were used, all being medium-sized Filipino coasters: Legazpi, Kolumbugan, and Bohol II. Between mid January and mid February, each of them made two round trips for a total of six deliveries of foodstuffs to Corregidor from the island of Panay as well as from Looc Cove in Batangas Province. Legazpi and Kolumbugan were victim to enemy interception on what would have been for each of them their third attempt. After those losses, it was decided that to send Bohol II again would have been futile since it was obvious that the Japanese blockade had effectively canceled out any hope of success.

Although the three ships which sailed from Corregidor had a short operational history, they had all told brought in 5,800 tons of rice and other foodstuffs together with 400 head of livestock. It was not enough to stave off surrender, but it must have made the last days

of the siege a bit more bearable.

Three days after the reserves of the Commonwealth were evacuated, however, matters came to a head. On February 5, 1942 General Valdes went to Bataan to inspect the troops and confer with Filipino and American officers. He returned to Corregidor that evening; one can possibly infer he then made a report to the President. What is explicitly recorded in the Diary of Gen. Basilio Valdes, on February 6, 1942 is that the following took place:

The President called a Cabinet Meeting at 9 a.m. He was depressed and talked to us of his impression regarding the war and the situation in Bataan. It was a memorable occasion. The President made remarks that the Vice-President refuted. The discussion became very heated, reaching its climax when the President told the Vice-President that if those were his points of view he could remain behind as President, and that he was not ready to change his opinion. I came to the Presidents defense and made a criticism of the way Washington had pushed us into this conflict and then abandoning us to our own fate. Colonel Roxas dissented from my statement and left the room, apparently disgusted. He was not in accord with the President’s plans. The discussion the became more calm and at the end the President had convinced the Vice-President and the Chief Justice that his attitude was correct. A telegram for President Roosevelt was to be prepared. In the afternoon we were again called for a meeting. We were advised that the President had discussed his plan with General MacArthur and had received his approval.

The great debate among the officials continued the next day, as recounted in the Diary of General Basilio Valdes, February 7, 1942:

9 a.m. Another meeting of the Cabinet. The telegram, prepared in draft, was re-read and corrected and shown to the President for final approval. He then passed it to General MacArthur for transmittal to President Roosevelt. The telegram will someday become a historical document of tremendous importance. I hope it will be well received in Washington. As a result of this work and worry the President has developed a fever.

The end results was a telegram sent to Washington. See Telegram of President Quezon to President Roosevelt, February 8, 1942:

The situation of my country has become so desperate that I feel that positive action is demanded. Militarily it is evident that no help will reach us from the United States in time either to rescue the beleaguered garrison now fighting so gallantly or to prevent the complete overrunning of the entire Philippine Archipelago. My people entered the war with the confidence that the United States would bring such assistance to us as would make it possible to sustain the conflict with some chance of success. All our soldiers in the field were animated by the belief that help would be forthcoming. This help has not and evidently will not be realized. Our people have suffered death, misery, devastation. After 2 months of war not the slightest assistance has been forthcoming from the United States. Aid and succour have been dispatched to other warring nations such as England, Ireland, Australia, the N. E. I. and perhaps others, but not only has nothing come here, but apparently no effort has been made to bring anything here. The American Fleet and the British Fleet, the two most powerful navies in the world, have apparently adopted an attitude which precludes any effort to reach these islands with assistance. As a result, while enjoying security itself, the United States has in effect condemned the sixteen millions of Filipinos to practical destruction in order to effect a certain delay. You have promised redemption, but what we need is immediate assistance and protection.We are concerned with what is to transpire during the next few months and years as well as with our ultimate destiny. There is not the slightest doubt in our minds that victory will rest with the United States, but the question before us now is : Shall we further sacrifice our country and our people in a hopeless fight? I voice the unanimous opinion of my War Cabinet and I am sure the unanimous opinion of all Filipinos that under the circumstances we should take steps to preserve the Philippines and the Filipinos from further destruction.

Again, by most accounts, there was great alarm in Washington over the implications of the telegram, and after consultations with other officials, a response was sent. See Telegram of President Roosevelt to President Quezon, February 9, 1942:

By the terms of our pledge to the Philippines implicit in our 40 years of conduct towards your people and expressly recognized in the terms of the McDuffie—Tydings Act, we have undertaken to protect you to the uttermost of our power until the time of your ultimate independence had arrived. Our soldiers in the Philippines are now engaged in fulfilling that purpose. The honor of the United States is pledged to its fulfillment. We propose that it be carried out regardless of its cost. Those Americans who are fighting now will continue to fight until the bitter end. So long as the flag of the United States flies on Filipino soil as a pledge of our duty to your people, it will be defended by our own men to the death. Whatever happens to the present American garrison we shall not relax our eiforts until the forces which we are now marshaling outside the Philippine Islands return to the Philippines and drive the last remnant of the invaders from your soil.

Still, seizing the moment, the Commonwealth officials pursued their proposal; see Telegram of President Quezon to President Roosevelt, February 10, 1942:

I propose the following program of action: That the Government of the United States and the Imperial Government of Japan recognize the independence of the Philippines; that within a reasonable period of time both armies, American and Japanese, be withdrawn, previous arrangements having been negotiated with the Philippine government; that neither nation maintain bases in the Philippines; that the Philippine Army be at once demobilized, the remaining force to be a Constabulary of moderate size; that at once upon the granting of freedom that trade agreement with other countries become solely a matter to be settled by the Philippines and the nation concerned; that American and Japanese non combatants who so desire be evacuated with their own armies under reciprocal and appropriate stipulations. It is my earnest hope that, moved by the highest considerations of justice and humanity, the two great powers which now exercise control over the Philippines will give their approval in general principle to my proposal. If this is done I further propose, in order to accomplish the details thereof, that an Armistice be declared in the Philippines and that I proceed to Manila at once for necessary consultations with the two governments concerned.

But it was not to be; the next day the reply from Washington came. Telegram of President Roosevelt to President Quezon, February 11, 1942:

Your message of February tenth evidently crossed mine to you of February ninth. Under our constitutional authority the President of the United States is not empowered to cede or alienate any territory to another nation.

In the Philippine Diary Project, the despondent response to this telegram is recorded. See Diary of Gen. Basilio Valdes, February 11, 1942:

Had a Cabinet Meeting. The reply of President Roosevelt to President Quezon’s radio was received. No, was the reply. It also allowed General MacArthur to surrender Philippine Islands if necessary. General MacArthur said he could not do it. The President said that he would resign in favor of Osmeña. There was no use to dissuade him then. We agreed to work slowly to convince him that this step would not be appropriate.

By the next day, cooler heads had prevailed; the response was then sent to Washington. See Telegram of President Quezon to President Roosevelt, February 12, 1942:

I wish to thank you for your prompt answer to the proposal which I submitted to you with the unanimous approval of my war cabinet. We fully appreciate the reasons upon which your decision is based and we are abiding by it.

From then on, the question became where it would be best to continue the operations of the government; and plans were resumed to move the government to unoccupied territory in the Visayas. The sense of an unfolding, unstoppable, tragedy seems to have overcome many involved. From the Diary of Gen. Basilio Valdes, February 12, 1942:

The President had a long conference with General MacArthur. Afterwards he sent for me. He asked me: “If I should decide to leave Corregidor what do you want to do?” “I want to remain with my troops at the front that is my duty” I replied. He stretched his hand and shook my hand “That is a manly decision; I am proud of you” he added and I could see tear in his eyes. “Call General MacArthur” he ordered “I want to inform him of your decision.” I called General MacArthur. While they conferred, I went to USAFFE Headquarters tunnel to confer with General Sutherland. When General MacArthur returned he stretched his hand and shook hands with me and said “I am proud of you Basilio, that is a soldier’s decision.” When I returned to the room of the President, he was with Mrs. Quezon. She stood up and kissed me, and then cried. The affection shown to me by the President & Mrs. Quezon touched me deeply. Then he sent for Manolo Nieto and in our presence, the President told Mrs. Quezon with reference to Manolo, “I am deciding it; I am not leaving it to him. I need him. He has been with me in my most critical moments. When I needed someone to accompany my family to the States, I asked him to do it. When I had to be operated I took him with me; now that need him more then ever, I am a sick man. I made him an officer to make him my aide. He is not like Basilio, a military man by career. Basilio is different, I forced him to accept the position he now had; his duty is with his troops”. Then he asked for Whisky and Gin and asked us to drink. Colonel Roxas and Lieutenant Clemente came in. We drank to his health. He made a toast: “To the Filipino Soldier the pride of our country”, and he could not continue as he began to cry.

On February 15, 1942, Singapore fell to the Japanese. That same day, February 15, 1942, General Valdes wrote,

At 9 a.m. the President called a meeting of his war cabinet. The matter of our possible exit from the rock was discussed. It was shown that the President could be of more help to General MacArthur and the general situation outside of the rock. The President conferred after with General MacArthur. He readily saw our point of view, to which was added my frequent report regarding the physical condition of the President. General MacArthur promised to radio asking for a submarine.

The Japanese are shelling Corregidor from the Cavite coast, probably Ternate.

Five days later, the Commonwealth government departed Corregidor to undertake an odyssey that would take it from the Visayas to Mindanao and eventually, Australia and the United States. See Escape from Corregidor by Manuel L. Quezon Jr. See also the diary entries of General Valdes for February 20, 1942, and February 21, 1942.

See also the diary of Felipe Buencamino III, earlier that same day, February 20, 1942:

Accompanied General to Mariveles. Was present in his conference with Col. Roxas. Javallera also attended meeting.

Roxas although colonel was easily the dominant personality of the meeting. He is a fluent, interesting and brilliant speaker.

Roxas explained military situation in Bataan. He said the convoy cannot be expected these days. He pointed out that Jap Navy controls Pacific waters. He stated that very few planes can be placed in Mariveles and Cabcaben airfields, certainly not enough to gain aerial superiority. “And,” he pointed out, “we don’t have fuel here, no ground crews, no spare parts!”

Roxas said Bataan troops must hold out as long as possible to give America, time to recover from initial gains of Japs who will attack Australia after Bataan.

Roxas said that Corregidor questions a lot of our reports.

Roxas said that evacuees are a big problem. They are thousands and they must be fed and they are in a miserable pitiful condition. He is thinking of sending them to Mindoro by boat that wil bring food here from Visayas.

Roxas revealed that thousands of sacks of rice good for a couple of days were brought to Corregidor by Legaspi from Cavite.

Though never publicized (for obvious reasons) by the Americans, the proposal to neutralize the Philippines was viewed important enough by Filipino leaders to merit the effort to ensure the proposal would be kept for the record.

From the Diary of Gen. Basilio Valdes, April 11, 1942:

The President called a Cabinet meeting at 3 p.m. Present were the Vice-President, Lieutenant Colonel Soriano, Colonel Nieto and myself. He discussed extensively with us the war situation. The various radiograms he sent to President Roosevelt and those he received were read. All together constitute a valuable document of the stand the President and his War Cabinet has taken during the early part of the war. The meeting was adjourned at 6 p.m.

In the Philippine Diary Project, this account by an unnamed officer to Francis Burton Harrison, recorded in his diary on June 13, 1942, gives an insight into the frame of mind of officers and soldiers at the front even as the debate was going on:

Supplies for besieged armies on Corregidor & Bataan: An officer told me: ‘All through the battle of Bataan we expected relief and reinforcements, though we knew the American Pacific Squadron had been temporarily put out of action at Pearl Harbor. On my first trip back from the front at Bataan to see General Sutherland on Corregidor the boys in the trenches had asked me to bring them food, tobacco and whiskey. This was on February 3rd; on February 18th I was again sent from the front on an errand to Corregidor, and this time all that the boys asked me to bring back was only “good news”–i.e., of relief coming. We all expected help until we heard President Roosevelt’s address on February 22nd. The truth about the sending of supplies is as follows: three convoys started from Australia. The first was diverted to Singapore; the second to the Dutch East Indies, and the third, consisting of three cargo boats started at last for the Philippines. Two of the vessels turned back and went to the West coast of Australia–to Brisbane. One boat, the Moro vessel Doñañate (?) got through to Cebu; it carried 1,000 tons of sugar and 1,000 tons of rice, both commodities we already had in the Visayas, so it was like carrying coals to Newcastle. Very little of this got through to Corregidor and Bataan, because of the blockade. Another vessel went aground near Leyte but the cargo was salvaged. We understood that after Pearl Harbor, the American Navy could not convoy supplies to us. Nor, of course, could they strike directly at the Japanese Navy as had always been the plan.’

Francis Burton Harrison’s diary entry June 12, 1942 and for June 22, 1942 also has a candid account by Quezon of this whole period and his frame of mind during that period.

June 12, 1942:

When we were alone together once more, I asked Quezon why, when he was on Corregidor and refused the Japanese offer of “independence with honor,” he had been so sure in staking the whole future on confidence in a positive victory over Japan. He replied: “It is the intelligence of the average American and the limitless resources of your country which decided me. The Americans are, of course, good soldiers, as they showed in Europe during the last war, but as for courage, all men are equally courageous if equally well led. Merely brave men certainly know how to die–but the world is not run by dead men.” He cited the case of the Spartans and the Athenians. “What became of the Spartans?” And then he added that in making on Corregidor that momentous decision, he “wasn’t sure.”

It seems Harrison was quite interested in this question and on June 22, 1942 he got Quezon to expound on the situation in February at greater length:

Exchange of cables between Quezon in Corregidor and Roosevelt: Quezon advised him that he was in grave doubts as to whether he should encourage his people to further resistance since he was satisfied that the United States could not relieve them; that he did not see why a nation which could not protect them should expect further demonstrations of loyalty from them. Roosevelt in reply, said he understood Quezon’s feelings and expressed his regret that he could not do much at the moment. He said: “go ahead and join them if you feel you must.” This scared MacArthur. Quezon says: “If he had refused, I would have gone back to Manila.” Roosevelt also promised to retake the Philippines and give them their independence and protect it. This was more than the Filipinos had ever had offered them before: a pledge that all the resources and man power of United States were back of this promise of protected independence. So Quezon replied: “I abide by your decision.”

I asked him why he supposed Roosevelt had refused the joint recommendation of himself and MacArthur. He replied that he did not know the President’s reasons. Osmeña and Roxas had said at the time that he would reject it. Roosevelt was not moved by imperialism nor by vested interests, nor by anything of that sort. Probably he was actuated by unwillingness to recognize anything Japan had done by force (vide Manchuria). Quezon thinks that in Washington only the Chief of Staff (General Marshall) who received the message from MacArthur in private code, and Roosevelt himself, knew about this request for immediate independence.

When Quezon finally got to the White House, Roosevelt was chiefly concerned about Quezon’s health. Roosevelt never made any reference to their exchange of cables.

Quezon added that, so far as he was aware, the Japanese had never made a direct offer to the United States Government to guarantee the neutrality of the Philippines, but many times they made such an offer to him personally.

“It was not that I apprehended personally ill treatment from the Japanese” said Quezon; “What made me stand was because I had raised the Philippine Army–a citizen army–I had mobilized them in this war. The question for me was whether having called them, I should go with this army, or stay behind in Manila with my people. I was between the Devil and the deep sea. So I decided that I should go where the army did. That was my hardest decision–my greatest moral torture. I proposed by cable to President Roosevelt that the United States Government should advise the Japanese that they had granted independence to the Philippines. This should have been done before the invasion and immediately after the first Japanese attack by air. The Japanese had repeatedly offered to guarantee the neutrality of an independent Philippines. This was what they thought should be done.” Quezon is going to propose the passage by Congress of a Joint Resolution, as they did in the case of Cuba, that “the Philippines are and of right out to be independent” and that “the United States would use their armed forces to protect them.”

When asked by Shuster to try to describe his own frame of mind when he was told at 5:30 a.m. Dec. 8 of the attack on Pearl Harbor, Quezon said he had never believed that the Japanese would dare to do it; but since they had done so, it was at once evident that they were infinitely more powerful than had been supposed– therefore he immediately perceived that the Philippines were probably doomed.

The question of the not just future, but present, status of the Philippines, particularly in light of the de facto government set up by the Japanese in Manila, led to this entry on February 25, 1943: in his diary, Harrison hears that,

It appears that Justice Frank Murphy presented to Roosevelt the plan for the recent announcement that Roosevelt has already recognized the Philippines as possessing the attributes of an independent nation by putting Quezon on the Pacific War Council and asking him to sign the United Nations declaration.

The United States published some of the documents cited above, and others, in a compendium covering the period from December 12, 1941, to December 12, 1942, which provides an insight into the internal discussions taking place in Washington and between Washington and Corregidor: See Official US-PH correspondence to open the PDF file of documents as published.

A postscript would come in the form a radio broadcast beamed to occupied Philippines. See the Inaugural Address of President Manuel L. Quezon, November 15, 1943:

I realize how sometimes you must have felt that you were being abandoned. But once again I want to assure you that the Government and people of the United States have never forgotten their obligations to you. General MacArthur has been constantly asking for more planes, supplies and materials in order that he can carry out his one dream, which is to oust the Japanese from our shores. That not more has been done so far is due to the fact that it was simply a matter of inability to do more up to the present time. The situation has now changed. I have it on good authority that General MacArthur will soon have the men and material he needs for the reconquest of our homeland. I have felt your sufferings so deeply and have constantly shared them with you that I have been a sick man since I arrived in Washington, and for the last five months I have been actually unable to leave my bed. But sick as I was, I have not for a moment failed to do my duty. As a matter of fact the conference which resulted in the message of President Roosevelt was held practically in my bedroom. Nobody knows and feels as intensely as I do your sufferings and your sacrifices, how fiercely the flame of hate and anger against the invader burns in your hearts, how bravely you have accepted the bitter fact of Japanese occupation. I know your hearts are full of sorrow, but I also know your faith is whole. I ask you to keep that faith unimpaired. Freedom is worth all our trials, tears and bloodshed. We are suffering today for our future generations that they may be spared the anguish and the agony of a repetition of what we are now undergoing. We are also building for them from the ruins of today and thus guarantee their economic security. For the freedom, peace, and well-being of our generations yet unborn, we are now paying the price. To our armed forces, who are fighting in the hills, mountains and jungles of the Philippines, my tribute of admiration for your courage and heroism. You are writing with your sacrifices another chapter in the history of the Philippines that, like the epic of Bataan, will live forever in the hearts of lovers of freedom everywhere.