On December 16-17, 1941 (around midnight, hence the event straddling two dates), the S.S. Corregidor, an inter-island steamship of the Compañia Maritima, hit a mine off Corregidor Island and sank, resulting in a tremendous loss of life.

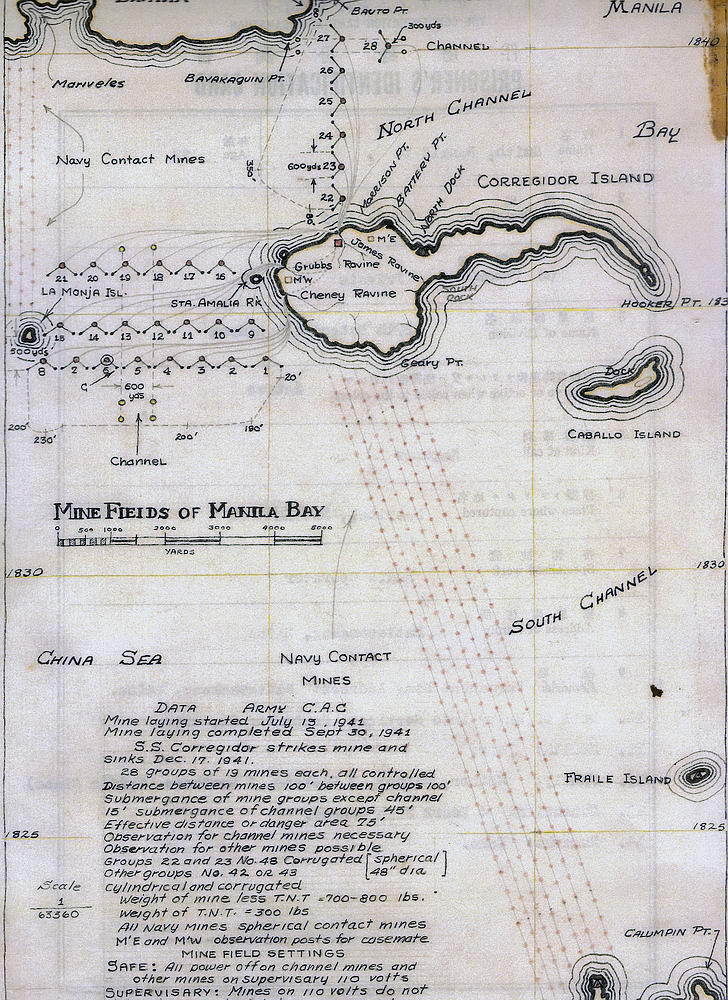

Here is a map of the area (click on this link for the original scan).

There is a very interesting discussion on the disaster, and the question of whether negligence was involved, and if so, who should be assigned blame, in the The Loss of the S.S. Corregidor thread of Corregidor Then and Now Proboards. Within the thread can be found recollections by George Steiger (an officer in Corregidor), Charles Balaza (serving in an artillery detachment on Corregidor) and others.

Here is a dramatic account by one of the survivors of the sinking of the ship, in the memoirs of Jose E. Romero (Not So Long Ago: A Chronicle of My Life, Times, and Contemporaries, Alemar-Phoenix, Quezon City, 1997 reprint):

The S.S. Corregidor Disaster

WAR HAVING BEEN DECLARED, the next day the National Assembly met at the house of Speaker Yulo to pass legislation giving the President powers to be able to cope with emergency. After that the members of Assembly were concerned with the problem of returning home to their provinces and their families. I was very much chagrined that close friends of mine had been able to take passage on the S.S. Legaspi that was making trips to my hometown, Dumaguete, via Cebu, a trip that took two days, without having difficulty from Japanese boats and planes. I was also chagrined to learn that my good friend, the District Engineer of my province who had come to Manila with me a few days previously, had been able to get out of Manila by way of the Bicol provinces and then made it to Samar and Leyte and back to our home province. A few days later, another boat was scheduled to depart for the South, including my hometown of Dumaguete. Passengers, including myself, were aboard when an hour later we were told to disembark by order of the U.S. Army, probably for fear of enemy action.

Inasmuch as the Japanese had already bombed Clark Field, Camp Nichols, Cavite, and Manila itself, particularly the Intendencia building and the Herald building and Santo Domingo Church, I thought it would be safer, being alone in Manila with my houseboys, for me to live in my office in the Legislative building. (The basement at the Legislative building had been sandbagged and was converted into an air-raid shelter.) I immediately arranged with the late Ramon Fernandez, whose boats were making trips to the Visayas, to advise me whenever any of his boats made a trip for the South, but this he never did. I had also arranged with my good friend, Salvador Araneta, who was then one of the principal owners of the FEATI (Far East Aviation Transport Co., Inc.), which owned the planes making trips between Manila, Iloilo, and Bacolod, to advise me whenever there was a chance to get on one of those planes. I was very much worried because, as already stated, I had come to Manila immediately after the election, and being very confident that in case of emergency I could easily return to my province either by a FEATI plane or by boat, I had not made sufficient provision for the maintenance of my family during my absence. In any event we had used up practically all of our financial resources during the political campaign and I had precisely come to Manila, among other things, to make arrangements to meet my immediate financial problems.

Although Mr. Araneta did his best to try to get an accommodation for me on the plane to the South, the man actually running the affairs of the FEATI was so swamped with demands for passage on his planes that even Mr. Araneta’s recommendation could not help me. One night I received a message from Mr. Araneta advising me that if I would go to Batangas that night, I might be able to get a passage on a plane. (The Manila airfield at Nichols had been bombed and was not safe for takeoff and landing of planes.) This was very difficult because the country was then under blackout orders, it was not safe to travel at night, and there was no certainty that I would get on the plane. It was the last trip that the plane made, so I missed this chance.

One day the member of the Assembly were advised that a special train was being reserved for us to go to Sorsogon. From there we could get launches or sailboats for Samar, Leyte, and our respective provinces in the Visayas. At the appointed day and hour many of us gathered at the Paco Station and we were hardly seated in the car when we were asked to come down because the Japanese had landed in Legaspi. A couple of days later, I saw my colleagues who like me had been living in the Legislative building rushing toward the Compañia Maritima office. One of them shouted to me that the S.S. Corregidor was leaving for the South. I immediately packed up the few things that I had and, together with a cousin of mine and his daughter who were living with me in the Legislative building, hied myself to the Compañia Maritima building. It was chaos there, with hundreds of people trying to get into the building to buy a ticket for the trip. A security guard, gun in hand, was at the door trying to prevent people from going into the building. I explained to him that I had an arrangement with Don Ramon Fernandez to get on the first boat going to the south, but he said that he knew nothing about the arrangement and would not let me in. My cousin, his daughter, and I left the building very disappointed when a little farther on we met Don Ramon’s nephew, Carlos, who today is still active with the shipping company. I explained my situation to him and he asked me whether I was really anxious to go on that trip. When I answered in the affirmative, he personally took me inside the office and helped me get a ticket for myself, my cousin, and his daughter. I also bought a ticket for a fellow townsman who wanted to return home but was without funds. But the danger of the trip was made manifest by our being asked to sign a waiver of any responsibility on the part of the shipping company in case a mishap occurred during the trip.

From the Compañia Maritima office and the Muelle de la Industria, we went to the South Harbor where the S.S. Corregidor was docked. There were hundreds of people and it seemed that there were many who got aboard even without tickets. I was delighted to find aboard Senator Villanueva, his recently married son and daughter, and their household help. He told me that he had been trying to contact me repeatedly the last few days, because he was anxious that we should go home together. In times of emergency like this, personal animosities among relatives are forgotten and the old family ties reassert themselves. I also met Captain Calvo of the boat, who had been a longtime friend of mine, with his pretty young wife that he had just married. He told me that I must be anxious to get back home under such conditions of danger. I told him that if he and his wife, my relatives and other people were willing to take the chance, there was no reason why I should not do the same. The boat was being located with ammunition and other military equipment for the South. I was quite nervous and I was told later that he had not wanted to make that trip. This probably partly explains why he was taking his wife along with him. I was also told later that on previous occasions, while passing the mined sections around Corregidor he had been warned that he was passing too close to the mines.

Probably the trip would not have been as risky as it was surmised. The plan was to land at the first port in the South at daybreak and from there the passengers would take sailboats or other means of transportation to the provinces which were still unoccupied by the Japanese. There were many times more passengers than should ordinarily have been allowed aboard. We stayed aboard for several hours and strict blackout was observed. Senator Villanueva and his family and I and my cousin with his daughter seated ourselves directly in front of a lifeboat as we thought we could quickly get on it in case of emergency. We were all furnished life belts and hundreds of other life belts were strewn around the deck. About midnight the boat started to leave in pitch darkness. I was half-asleep but noticed that light signals were being flashed from what I think was Corregidor Island. I was to learn afterward that the signals were to warn the captain of the boat that he was not on the right track. (The passage between Corregidor and the mainland in Manila Bay had been mined.) All of a sudden there was a dull thud and then an explosion. We had hit a mine. The boat shuddered as if mortally wounded. It did not sink immediately and the group already referred to who were seated near a lifeboat got aboard it.

Before the boat left, as already stated, we had been supplied with life belts. My companions were very prudent in having attached the life belts to their bodies, but I only held mine in my hands. A husky Spaniard had been saying that this was a bad joke we were playing with the life belts, but I told him that it was customary, even in peacetime, to have drill aboard the ships and practice the use of life belts. When we hit the mine this husky man grabbed my life belt, since he had not taken the precaution to provide one for himself. I insisted that the life belt was mine, but he claimed that it was his and proposed that we throw the life belt into the water, confident that later on, if we had to struggle for that life belt, as a much huskier man he would have the advantage. But the man from my province, whom I had helped to get a ticket on that trip and for which ticket I had paid, handed me another life belt. Again it was grabbed by another person. This faithful protege of mine handed me another one and still another one, but each time somebody would grab the life belt away from me. Remembering that I was the only one without a life belt and recalling that hundreds of life belts had been scattered on the deck in the early evening, I went down to the deck to see if I could find another life belt. At this moment, there was a second and more terrible explosion. It seemed that it was the boiler that exploded and the boat immediately sank headlong into the water. We were all drawn by the suction and had the water in those parts been deeper, we could not have returned to the surface.

When the boat reached the bottom and there was no more force of suction, I instinctively swam with all my force toward the surface, and when I reached the surface after what seemed an endless effort to reach it, it seemed this was a second life for me. Right in front of me was a life belt and a piece of board just enough for me to lie down on. If ever there are or were miracles, this certainly was one. I had gone into the water without a life belt and here right in front of me was the board of salvation and a life belt. I did not realize it then, but I had ugly cut in the head which must have been caused when the boat touched the bottom and my head hit something hard. I was too weak to tie on my life belt and it was really the board that saved me. I was too weak from loss of blood, so I only hung on to the board which, as I said, was just sufficient to keep my body afloat. Fortunately, it was as long as my body so that my body covered it almost entirely, otherwise other people who were floating around without support might have tried to grab it from me. I just lay over that board semi-conscious for several hours. Fortunately, the sharks that infest these waters must have been kept away by the explosion and by the oil from the sunken ship. About four hours later. I felt as if there were some bright lights. It was one of the P.T. or so-called mosquito boats that had been sent to rescue the survivors. I looked up and one of the American crewmen threw me a life belt which was tied to a rope that he held. I took hold of the life belt and he pulled me toward the boat. I must have looked like a real mess, covered all over with oil from the boat that sank and with the blood of my head over my face. I just lay there on that boat while we were being taken to Corregidor. It was just beginning to dawn when we docked at the harbor of Corregidor. I will never forget, especially after seeing the callousness and cruelty of the Japanese later, seeing one of the American soldiers who had come to the dock to meet the survivors take particular notice of me, saying, “This man is badly hurt.” He immediately ran up the gangplank, took me in his arms, loaded me into the car that he was driving, and then rushed me like mad to the hospital in Malinta Tunnel. The others who were not so badly hurt were taken to Manila. Only about one-third of some one thousand people that were in the S.S. Corregidor were saved. Senator Villanueva and his son, my cousin and his daughter, as well as two of my colleagues, Representatives Ampig and Reyes of Iloilo and Capiz, respectively, perished in the disaster, as did the wife and children of Representative Dominador Tan. Representative Zaldivar, later Justice of the Supreme Court, survived.

In Corregidor Hospital

At the hospital in Malinta Tunnel, which I revisited later, the wound in my scalp was sewn up by a kind American doctor. Fortunately, the wound was only skin-deep and did not fracture my skull. When a Filipino nurse found out who I was, she made a lot of fuss about it and many people were soon coming to see me. (Much later when I was Secretary of Education, on a visit to Cabanatuan City, Nueva Ecija, I was fortunate to see her again with her husband.) Two of the young officers who visited me in Corregidor were from my town and province. A medic or medical assistant, an American, took very kind interest in me. (To anticipate my story, when I left Corregidor Hospital ten days after I entered it, I was to wear his civilian clothes as I had none of my own. I gave him my address and after the war when the House of Representatives, of which I was a member, was reconvened, one day an American came to my office and greeted me joyously. When I could not quite remember him, he said, “I was the one who sewed up your head in Corregidor.” It was a happy reunion. He gave me his address in the U.S. to which he was returning and when I was Ambassador to London, I unfailingly sent him a Christmas card. I did not receive any reply from him, but after the third or fourth time I sent him a card, I got a reply explaining that the reason he did not acknowledge my previous cards was that he did not know the address of the Philippine Embassy in London, not realizing that it would have been sufficient for him just to put the Philippine Embassy as address. He told me that he was working somewhere in the Middle East and was doing pretty well financially.)

I developed a slight case of pneumonia, but thanks to the sulfa drugs that had just recently been discovered, this danger to my health was averted.

To return to my story, next to my bed at the hospital was that of Captain Kelly of the United States Navy, a man made famous by a book written in the United States by American escapee during the War, entitled They Were Expendable—a bestseller. Like many Americans in Corregidor, they were still confident that military aid would come from the United State and that the Philippines would be retaken. But this was not to be for more than three years.

During my ten-day stay in Corregidor, from December 17, the day of the sinking of the Corregidor, until December 27 when we were ordered to evacuate to Manila, many prominent officials went to Corregidor. Among those who visited me were the Commanding General of Corregidor and the U.S. High Commissioner, Francis B. Sayre, Vice-President Osmeña and his family, ex-Speaker Roxas, and Chief Justice Jose Abad Santos. President Quezon and his family, however, who also arrived at Corregidor on Christmas Eve, did not visit me. When casually one night I saw him and Mrs. Quezon, he did not even talk to me. I think he was ill and depressed when he saw me with my bandaged head and, perhaps thinking that I was more badly hurt than I really was, he simply was too depressed to talk to me. However, Mrs. Quezon who was seated next to me while we were seeing a movie just outside the entrance to Manila Tunnel during a lull in the bombing by the Japanese, held my hand and gave me words of comfort. From Vice-President Osmeña, I learned for the first time that my relatives by affinity, ex-Senator Villanueva and his son, had not survived the sinking of S.S. Corregidor, although the ex-Senator’s daughter-in-law, who was expecting a baby (and who is still very much alive), and two maids survived.

Christmas Eve was celebrated in Corregidor, and in my condition, away from my family, it was indeed a sad Christmas Eve for me. The singing of Christmas carols by the American and Filipino nurses and other personnel only added poignancy to my depressed spirit. On December 27 an order was received from General Douglas MacArthur for the evacuation of all civilians in Corregidor to Manila, as the Japanese were fast approaching Manila. The medic who took such interest in me suggested that I ask President Quezon to contact General MacArthur and get him to make an exception in my case by allowing me to stay in Corregidor. I contacted Mr. Roxas, who immediately got in touch with President Quezon and who in turn tried to get in touch with General MacArthur. However, General MacArthur was busy directing the withdrawal of USAFFE troops to Bataan and could not be contacted. Mr. Roxas urged me, however, to go to Manila. He said that I could get better medical treatment there and, besides, the boat leaving for Manila might be the last one that could make the trip as, with the arrival of the Japanese, Manila would be isolated from Corregidor. So I decided to leave.

We left again in pitch darkness, as complete blackout was ordered everywhere. I shall not forget another American soldier who took me in his car to the waiting ship and then removed his overcoat and placed it over me. After my experience on the S.S. Corregidor, to travel again in complete darkness could not but inspire fear in me, but we made the trip uneventfully. Upon arrival in the South Harbor, we were placed in a covered truck where it was also very dark. The driver had to stop at every street corner to find his way, and finally I was deposited at the Philippine General Hospital which was then under the direction of my good friend, the late Dr. Augusto Villalon. I was placed under the direct care of Dr. Santos Cuyugan, who was a specialist in wounds and burns. Because of the infection of my wound, it took about three months to heal, although it was only a superficial one

The Philippine Diary Project contains several points of view discussing the S.S. Corregidor disaster. The earliest one appears in an entry in the diary of Teodoro M. Locsin, December 16, 1941:

Today the inter-island vessel Corregidor struck a mine near the mouth of Manila Bay and sank in a few minutes. The ship was packed to the gunwales with passengers leaving the city for the southern islands, thus reintroducing the “Samarra” theme.

The number of people on board was estimated at from 600 to 1,000. The exact number may never be known. Government officials used their influence to make the ship’s agents issue them and their friends tickets. Many went up the gangplanks just before the boat sailed, thinking to get their tickets from the purser afterward, when the boat was out at sea. Each, in one way or another, properly sealed his fate.

Later in the day, I was shown a wire from a man in Iloilo asking a friend in the city to secure a ticket for his mistress on the Corregidor. The war caught the woman in Manila and the man wanted her with him. The friend, I need not say, got the ticket.

Locsin, then a young newsman in the Philippines Free Press, would have been among the first to receive important news. Others got the day after. Fr. Juan Labrador OP, December 17, 1941 mentions how most other people got the news, and details that shocked the public:

At noontime, an “extra” of the dailies announced the great catastrophe of the vessel “Corregidor”. This was the heaviest and fastest of the boats anchored at the river. It set sail the night before without previous notice. Nevertheless, it was teeming with passengers destined for the Visayas. Around midnight, it hit a mine near the island of Corregidor and in three to five minutes it was swallowed up by the black waters of Manila Bay. It cannot be ascertained how many lives were lost. The Compañía Marítima does not have a list of the passengers. Many had filtered in without paying the fare, or mounted aboard with the idea of paying later on. Only 200 passengers were rescued, and the number of those drowned is estimated at 600 to 800.

Among the passengers were assemblymen, students from the South, and well-known families, including the brothers of the Archbishop of Cebu, one of whom was a professor and secretary of the Faculty of Law of the University of Santo Tomas; the other was a member of the Assembly. The assemblyman drowned, but the faculty member of UST was saved after swimming and floating for six hours. Those who were trapped in the cabins—women and children, for the most part—are forever buried in the bosom of the sea. Even among those who were on deck and had time to jump overboard, many were drowned for lack of lifesavers or for their inabiity to resist the current of the waves.

It was the first great tragedy of the war, and God permit that it be the last.

A young officer in the Philippine Coastal Patrol (the fledgling Philippine Navy) wrote about the tragedy as he received the news from colleagues in the US Navy. See Ramon Alcaraz, December 17, 1941:

By night time, the tragedy was compounded by the sinking of S.S. Corregidor in our own defensive minefields guarding the entrance to Manila Bay west of Corregidor Fortress. S.S. Corregidor is one of the best among our inter-island commercial vessels with civilian and military personnel aboard bound for Visayas and Mindanao.

Loaded also are Artillery pieces, equipment and supplies of the 101st FA, and other Vis-Min Units. From initial scant report I got from my Mistah Alano, ExO of Q-111 that participated in the rescue, he said the ship hit a mine and sunk so fast virtually all passengers went down with the ship including her Captain. There were very few survivors. The mined area is under the responsibility of the Harbor Defense and PT RON 3. I should know more details about this tragedy after I talk with some of my comrades on duty then at PT RON 3.

Five days later, Alcaraz had more information about the tragedy. See Ramon Alcaraz, December 22, 1941:

I also talked with Ens. George Cox, CO PT 41 on duty when S.S. Corregidor sunk five days ago. He said PT 41 was leading the ill fated ship at the channel but suddenly, all at once, the S.S. Corregidor veered course towards the minefields and his efforts to stop her were to no avail. There was a loud explosion after hitting a mine, the ship sank so fast virtually all aboard went with her including the ship captain. There were very few survivors.

Events would rapidly overtake the S.S. Corregidor disaster. See December 24-25, 1941 in diaries; The Great Escape of the S.S. Mactan: December 31, 1941; Evacuation of the Gold Reserves of the Commonwealth, February 3, 1942; The debate on taking the Philippines out of the war: February 6-12, 1942; Bataan, 1942: views of a father and his son; Life, death, decisions, during the Japanese Occupation; Diary entries on the Leyte Landing: October, 1944; and The Battle of Manila, Feb. 3-March 3, 1945 for more features on entries in the Philippine Diary Project.

Update: The Maritime Review blog has the latest findings of NAMRIA, see Revisiting the Sinking of the SS Corregidor.