(Above: February 27, 1945: Douglas MacArhur and Sergio Osmeña at the ceremony in Malacañan Palace in which the civilian authority of Commonwealth was restored in the capital)

This year marks the 75th anniversary of the surrender of Japan and the end of World War II in the Pacific. The Philippine Diary Project contains three unique perspectives on the final month of the conflict, from the time of the Potsdam Declaration from Berlin in July, 1945, to the landing of the Allies in Tokyo in August, 1945. They are the points of view of:

First, Leon Ma. Guerrero, journalist and diplomat, who was with the Philippine Second Republic’s embassy in Tokyo. He’d started his diary (as published, anyway) on January 1, 1945. Guerrero features prominently in the Bataan and Death March diary of his friend, Felipe Buencamino III, with whom Guerrero served in the Intelligence Section of the Philippine Army. After the fall of Bataan, Guerrero went on to continue in propaganda, this time, on behalf of the Japanese, maintaining his pen name of Ignacio Javier.He would go on to join the embassy established by Jorge Vargas in Tokyo. A lawyer, diplomat, and former journalist, Guerrero recorded events in the Japanese capital and the resort town in which diplomats had evacuated, from the privileged position of an embassy staffer, with the shrewd eye of someone who’d already had government and political experience, and a reporter’s gift for jotting down the telling detail.

Second, there is the diary of Salvador H. Laurel, the son of Japanese Occupation-sponsored President Jose P. Laurel, who was with his father in exile in Nara, Japan; his father had assigned him to keep a diary from the start of their evacuation from Manila to Baguio in December, 1944, and then on to their flight into exile in Japan. He combines the perspective of a young man and someone in the unique position of being able to observe the dying moments of his father’s regime.

Third, writing in Iwahig Penal Colony in Palawan, there is the diary of Antonio de las Alas, who had been Minister of Finance in the Laurel government, a fixture in the prewar government (having served in the Quezon government and, at the oubreak of the war, he had just been elected to the senate), and who was under Allied detention for collaborating with the Japanese. His is a senior government official’s perspective, familiar with both the Americans and the Japanese, and observing the changes in affiliations and alliances as senior officials like himself went into eclipse.

Our story begins in mid-July, with the meeting of the “Big Three” –Winston Churchill, Harry S. Truman and Joseph Stalin– in the capital of defeated Germany: in a suburb of Berlin called Potsdam, to be exact.

The Potsdam Conference was the follow-up to the Yalta Conference, where Franklin D. Roosevelt, Winston Churchill, and Joseph Stalin had agreed that three months after the defeat of Germany, Russia would join the United States and Great Britain in waging war against Japan. Russia had maintained neutrality in the Pacific War, but the Western Allies, concerned about the expected immense casualties that an invasion of Japan would cost, wanted Russia to join the fight.

In the meantime, also because of the anticipated great cost in lives of a Japanese invasion, the United States had pursued the Manhattan Project and Harry S. Truman had authorized the use of the atom bomb against Japan.

On July 16, 1945, the atomic bomb had been successfully tested in New Mexico: Truman informed Churchill and Stalin of this fact in Potsdam the next day, July 17.

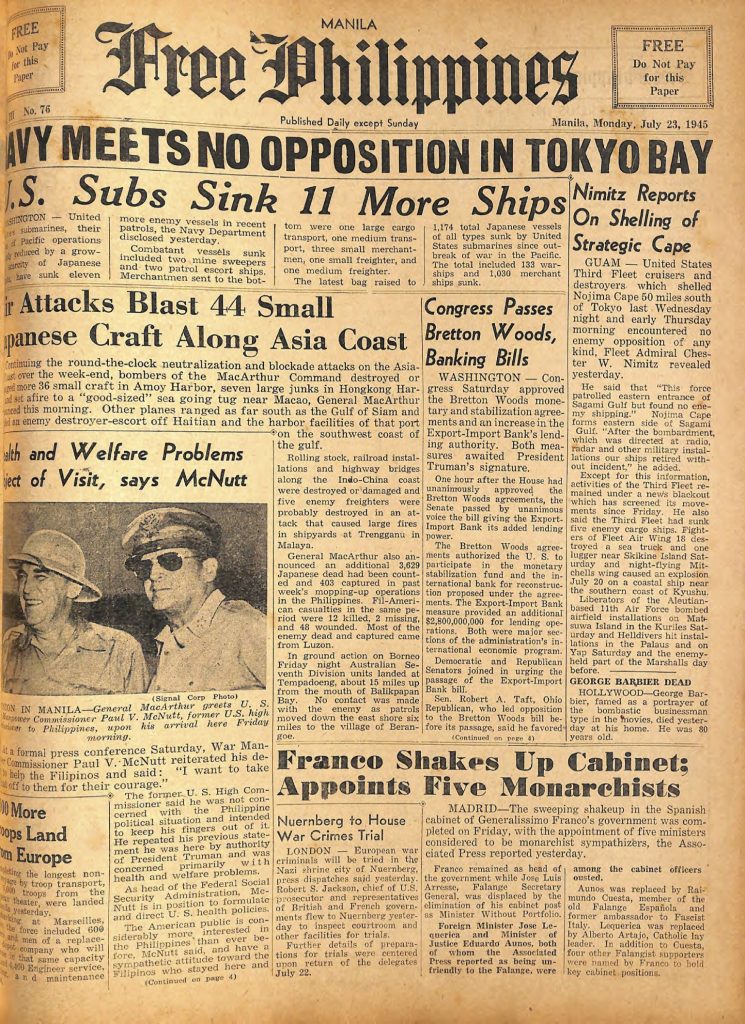

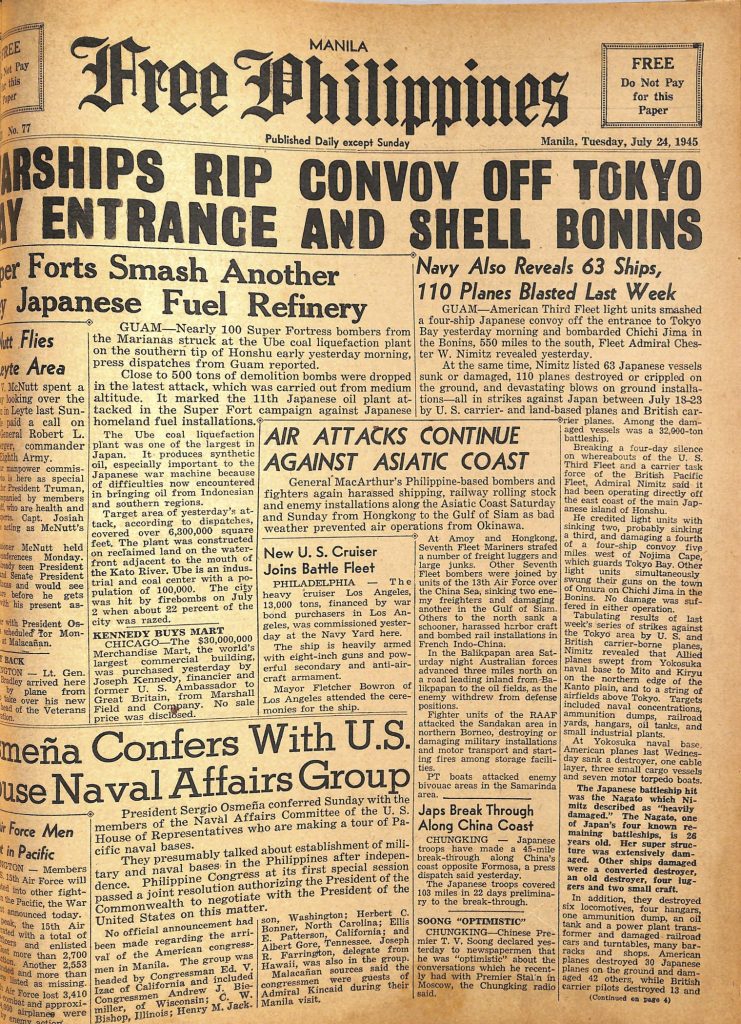

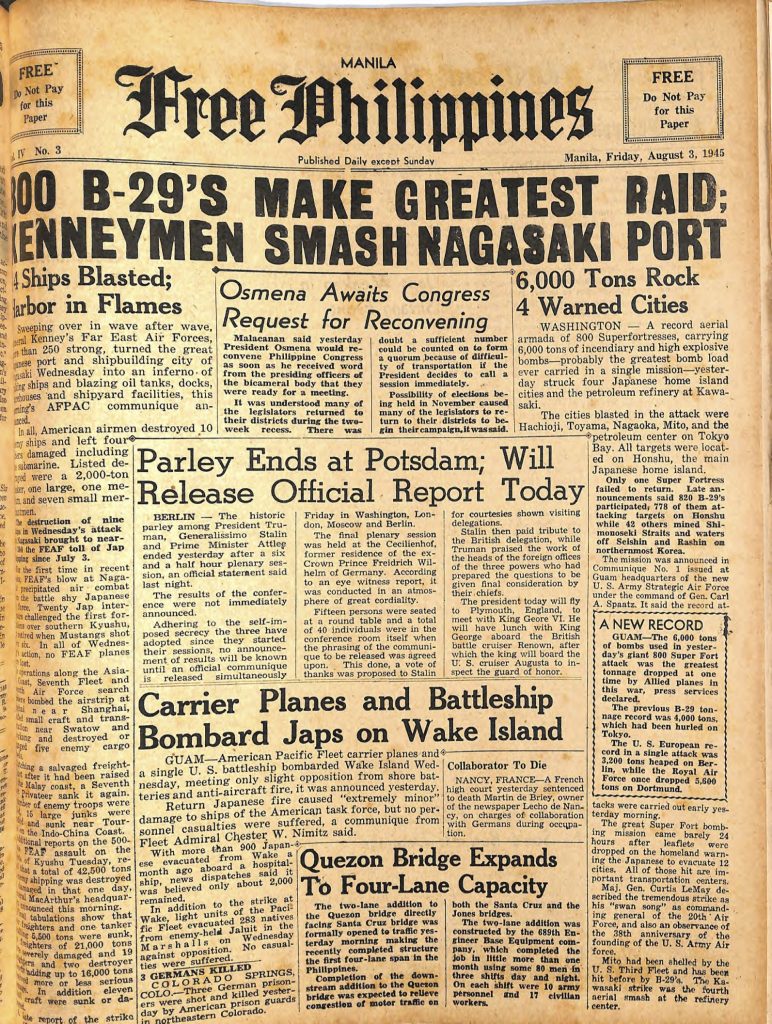

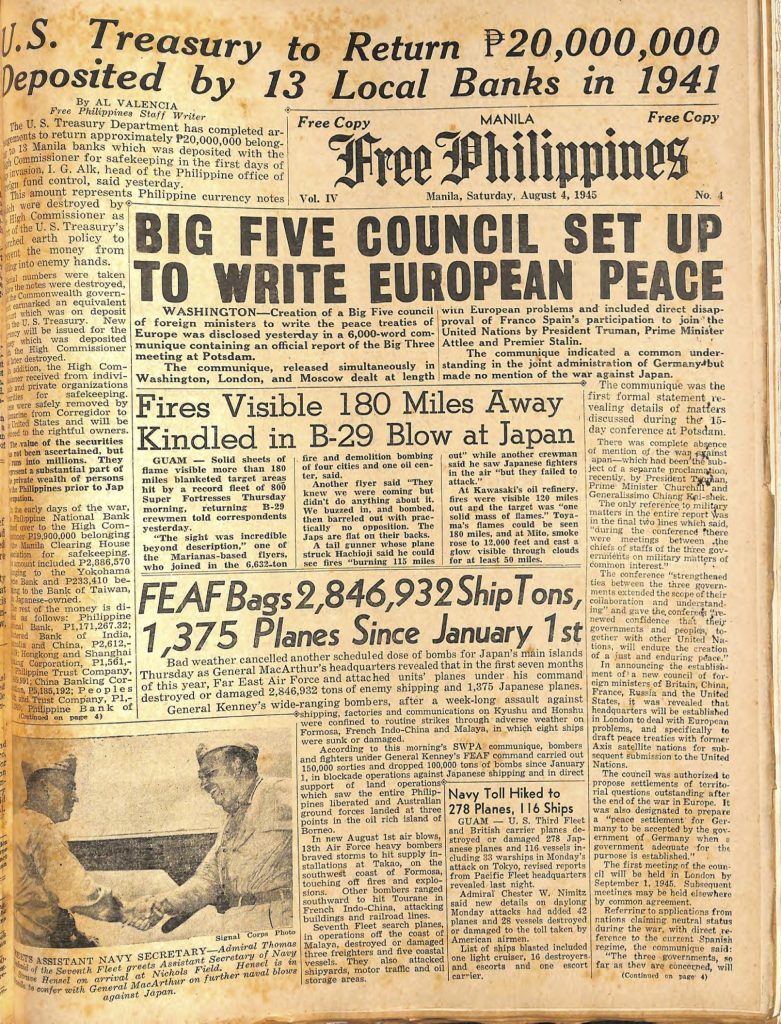

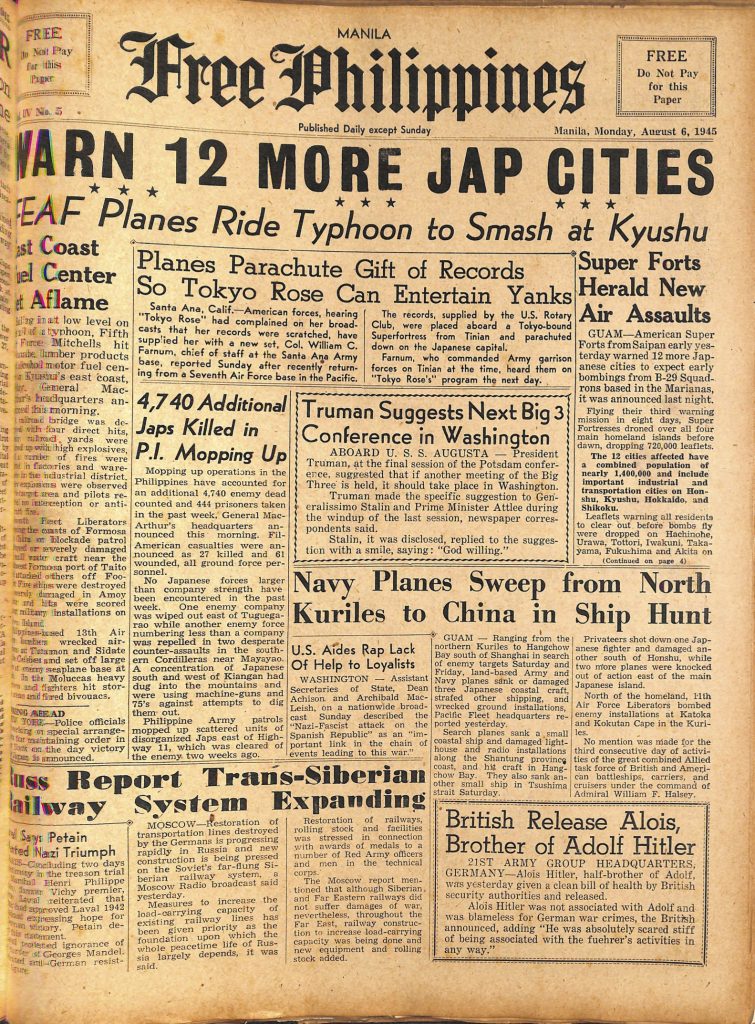

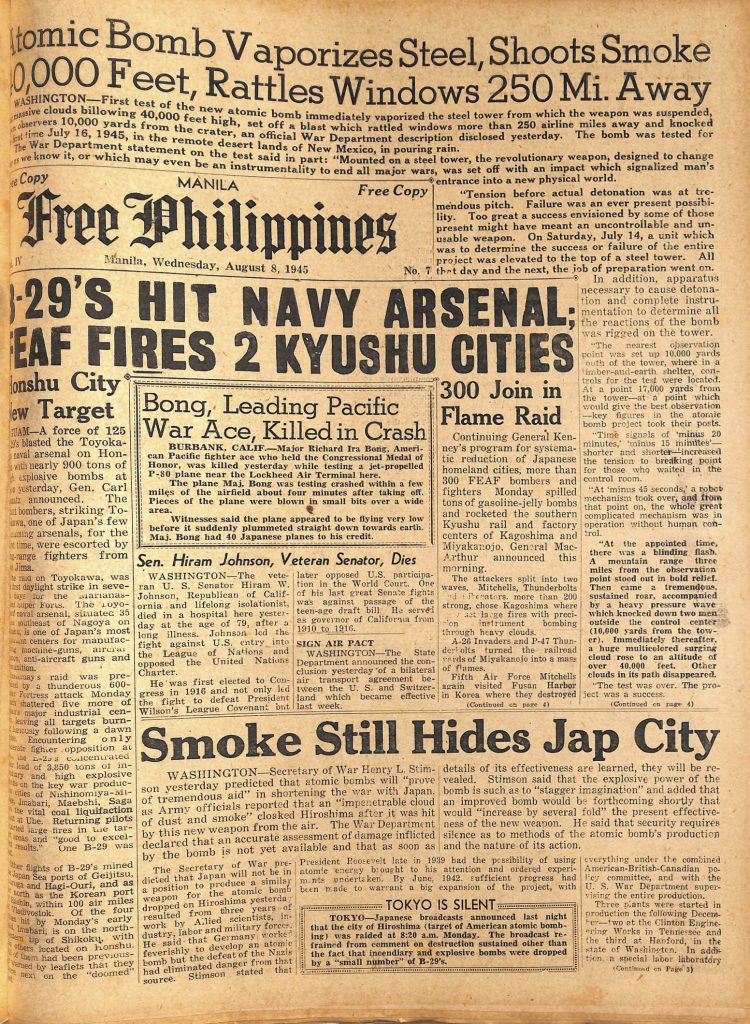

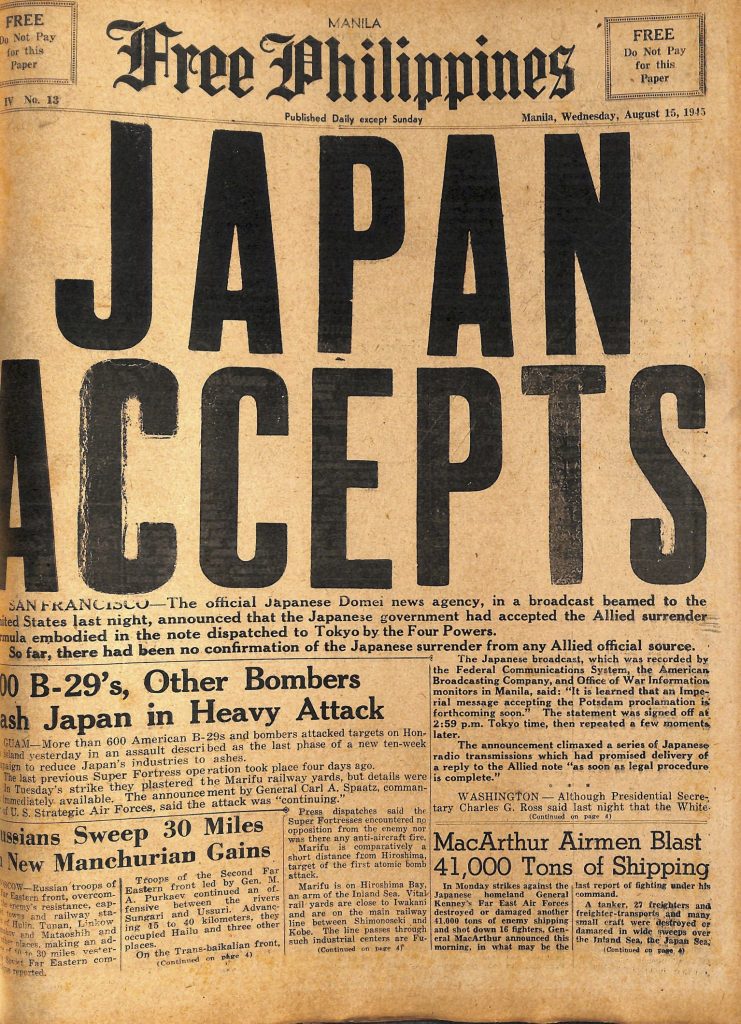

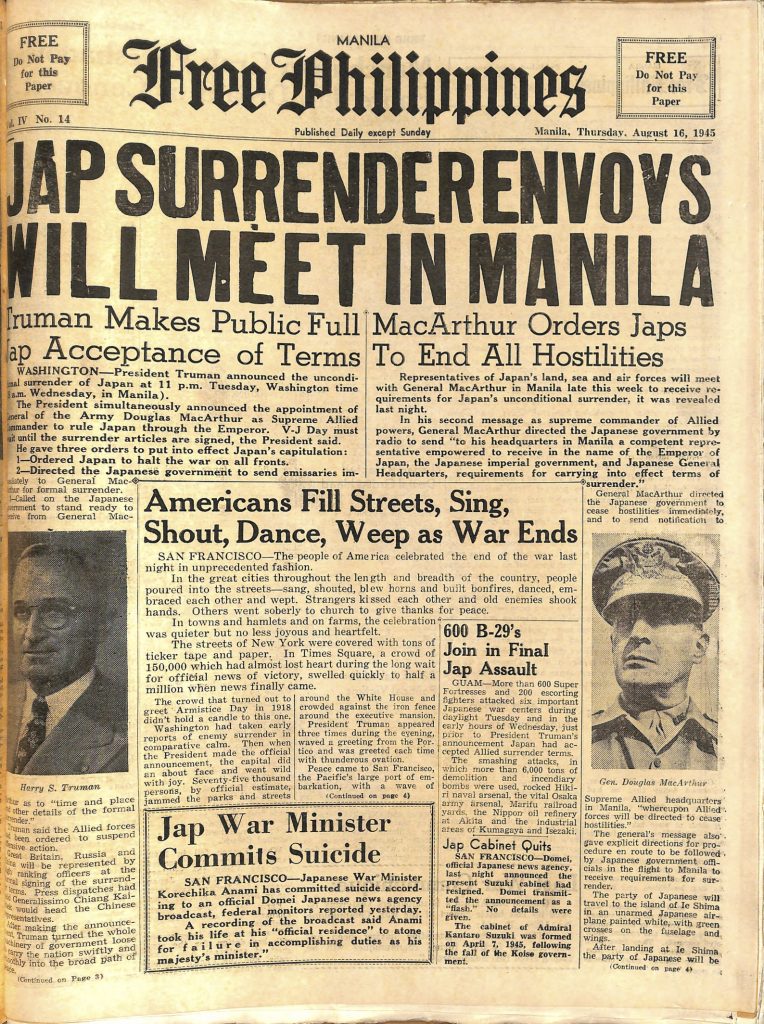

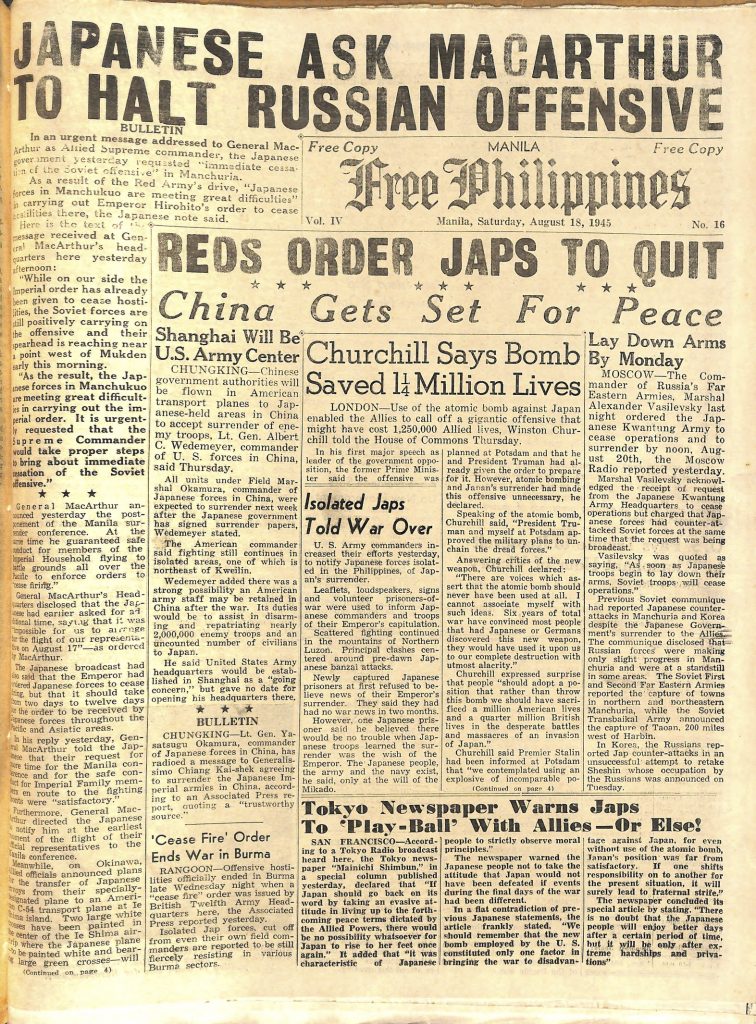

What follows contains day headings in italics come from The Last Days of Imperial Japan 1945 – 1951. Day information in underlined italics comes from World War Two in the Pacific: Timeline of Events 1941-1945, while the days also feature the front page of Free Philippines, the newspaper put out by the Office of War Information of the U.S. Army in the Philippines.

A quick summary of how the focus of events had shifted to the looming task of planning “Operation Olympic” –the expected invasion of Japan in 1946:

July 5, 1945 – Liberation of Philippines declared.

July 10, 1945 – 1,000 bomber raids against Japan begin.

July 14, 1945 – The first U.S. Naval bombardment of Japanese home islands.

July 16, 1945 – First Atomic Bomb is successfully tested in the U.S.

July 22, 1945

Walking in the resort town of Gora in the outskirts of Tokyo, young diplomat (and former journalist and Bataan veteran) Leon Ma. Guerrero jots down some sounds and sights:

Sights in the mountain resort of Gora:

A Japanese sporting a buckle labeled “Philippine Commonwealth”;

A Japanese boy playing with a model airplane but this one carried an American star on its wings instead of the Japanese sun;

A rickety brown inn along a rocky slope, full of school-children evacuated from Tokyo and Yokohama. The parents of two-thirds of them had perished in the last air-raids. Somehow the teachers had broken the news to their charges after many days of troubled apprehension. Perhaps the orphans wept that day and perhaps they still do it at nights but when I passed by, they were laughing and chasing one another in the chill sunlight.

July 23, 1945

A one-line entry by Leon Ma. Guerrero in Tokyo:

The railway volunteer fighting corps will be formally organized on the 1st of next month.

More substantial is Antonio de las Alas’ summary of news received in their detention cells in the Iwahig Penal Colony in Palawan:

The newspapers bring two pieces of news; one elated us, and the other alarmed us.

The first seems to indicate an early end of the war. United Press reports in New York that the United States government administration is taking steps to draft the United States unconditional surrender terms. New York Herald Tribune states that the possible terms as reported from reliable sources are the following: (1) Return of all territories seized by force; (2) Complete destruction of Japanese fleet and air force; (3) Dismantling of all shipbuilding facilities capable of turning out air crafts and munitions; (4) Japan will not be invaded, only a token “supervisory force” will be sent to Japan; (5) Japan is to retain her form of government, including the Emperor, and to manage her own political, economic and social affairs; and (6) Japan may be supplied with iron, coal, oil and other resources needed for civilian use.

Some parts of the above terms need clarification. For instance, what shall be done with Manchuria, Korea and Formosa?

If I were Japan, I would grab peace under the above terms. Japan is already beaten. With the hundreds of superfortresses, her annihilation or almost complete destruction is assured. Furthermore, due to her own fault, her dream of union among the countries of Greater East Asia has been blasted. Because of her record in these countries, it will take a century before her nationals will be welcomed in these countries. Not only did she disqualify herself to be the leader of any union to be organized here, but she will probably not even be admitted until she shows that she can treat other people as civilized people do. China may want to be the leader. If Manchuria and Formosa are returned to her, she will be the strongest nation in the world and may even dominate the world. The Chinese are not only good businessmen, but they have also shown themselves to be good soldiers. But they were also shown to be cruel at times. I believe that for the safety of the Orient, China be divided into at least three nations: North and South China, and Manchuria.

It is rumored that in Washington these terms for surrender were received with general approval.

He adds another item of news that will feature prominently in the weeks to come:

The above news must be related to other news. It is reported that Russia is acting as intermediary and that Stalin took with him to Berlin the surrender terms, evidently to submit them to the Conference between him, Truman and Churchill. Another news item is that before the Russian delegation left for Berlin, the Japanese Ambassador Sato, had a conference with Foreign Commissar of Foreign Affairs Molotov and with the Vice-Commissar.

Something must be in the offing. All of us expect or at least hope that termination of the war will come.

July 24, 1945

In Tokyo, Leon Ma. Guerrero reported that,

Near midnight on the 22nd a Japanese convoy moving under heavy rainclouds suddenly it came upon eight American destroyers about 20 kilometers off the southern end of Boso peninsula. Following an engagement of some 20 minutes “the enemy was routed to the south” while “a small fire was caused on one of the Nippon transports”. Such was the Japanese announcement today. The Americans for their part have announced wiping out the convoy.

July 25, 1945

In Tokyo, the sense that the noose is tightening around Japan is increasing, can be gleaned from Leon Ma. Guerrero’s summary of events and the reaction of the Japanese press:

For two weeks now the amazing American task force has raged like a typhoon along the Pacific coast of the Japanese homeland; yesterday it struck its most devastating blow so far. According to the joint army and navy communique which today, in headline type, covers fully one half of the Mainichi’s tabloid front-page, approximately 2,000 large and small American planes “repeatedly carried out attacks unprecedented in scale and scope” against four different army areas. The communique claimed only seven raiders shot down by 1:30 p.m. yesterday and admitted fires and “some other damage” in Osaka. This morning the radio said that more than 500 carrier-borne planes were back on the job.

Today’s Asahi tries to rationalize this spectacular disaster. “In coping with the latest enemy air-raids,” it says, “both our fleet and air-force have exercised patience and caution without developing a full-fledged attack. As a result a section of the public in the country has come to entertain the apprehension that the authorities concerned, in placing an excessive importance on storing up fighting power, have allowed our territory to be trampled underfoot by the enemy. Some even go to the length of doubting our fighting power itself. Such an attitude,” the Asahi says reprovingly, “is a remarkable error based on the failure to appreciate the war as a whole.”…

“Candidly speaking,” the Asahi concludes, “the present war situation is not necessarily advantageous to us. But once the enemy attempts to land, more advantageous fighting conditions will develop before us. We can say so decisively; it is an objective fact. Then if we utilize these strategic advantages with a vigorous fighting spirit, the war situation will turn favorable to us without fail.”

In Iwahig Penal Colony, Antonio de las Alas noted that,

Rumor is circulating that Russia had given an ultimatum to Japan to surrender to the United Nations within 72 hours. It is said also rumored that Japan has surrendered unconditionally. The Colonel and the Lieutenant deny that these rumors are true.

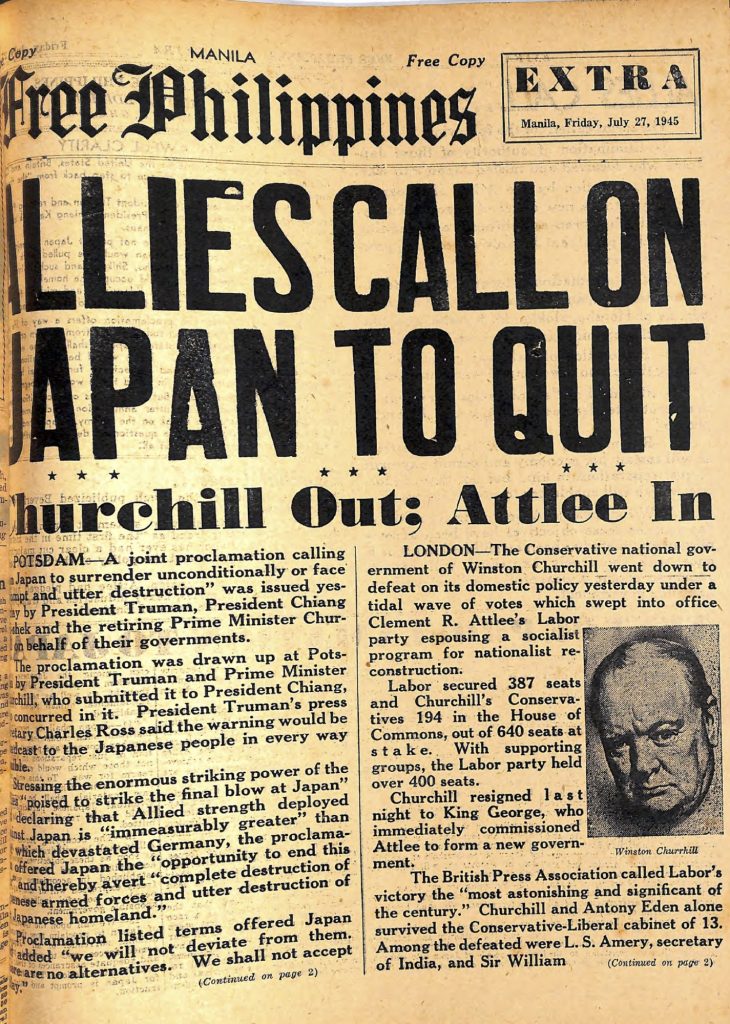

July 26, 1945: The Potsdam Declaration

On this day, Components of the Atomic Bomb “Little Boy” are unloaded at Tinian Island in the South Pacific.

The Potsdam Declaration was a final warning to Japan issued on July 26, 1945 issued by the United States, Great Britain, and China.

In his diary (because of the international date line), Leon Ma. Guerrero wasn’t yet aware of this; but his entry provides a snapshot of Japanese official posturing on the eve of what would mark the start of the end game for Japan. His entry is a masterpiece of sarcastic bemusement:

The Japanese learned “with trepidation” today that while the American task force is searing the imperial land with fire and steel, the emperor “is graciously engaged in state affairs, in high spirits despite his work.” Due to the destruction of the imperial palace “His Majesty is experiencing more inconveniences than before but he has had the graciousnesss to attend to state affairs in excellent health.”

The president of the board of information, who transmitted these facts at the inaugural meeting of branch-chiefs of the Dai Nippon Political Association, also recalled an anecdote on the emperor’s grandfather. When the great Prince Ito submitted his resignation as premier, the equally great Meiji answered with a sigh: “Alas, We cannot resign.”

Yesterday the Asahi also reported on the state of the Premier’s health. It seems that despite his advanced age (he will soon be 80), Suzuki is “rosy-cheeked and radiating health.” He has not been sick once in the four months since he took office. At that time an old shipmate, a retired navy doctor, had rushed up to Tokyo from Okayama and had appointed himself the new prime minister’s physician. He was now “thoroughly disgusted”; he had nothing to do. The old man’s blood pressure was 169; his weight had fallen off a bit from 22 to 20 kan (one kan equals 3.75 kilos or 6.23 pounds) but he had not suffered from it.

The secret of the premier’s health, it developed, was sleep; he slept at least 10 hours a day, retiring ay about 10 p.m. Not even an air-raid could make him lose his “precious sleep”. He received no visitors in the mornings, spending them “in speculation and thought”. For recreation he had a small garden; an inveterate smoker he had cut himself down to two cigars a day, since taking office and had allowed himself half a [illegible] each day. (one [illegible] equals 1.[illegible] liters).

An avid reader, he had lost his entire library in a fire-raid. But a grandson had found him a copy of the works of Laotsze in a second-hand bookstall and had pointed out a passage in this work which he considered the secret, not only of his administration, but of life itself. The passage: “The way to govern a great country is the same as to cook small fish. Cooking the fish quickly or over too strong a fire, breaks it up and spoils it. Whatever you do, do it slowly and well.

In the imperial cities along the storied rivers, in the startled villages of the northern coast, in the factory towns on the fabled highway of the Tokaido, by Inland Sea and the ravaged shores of Kyushu, while His Majesty graciously and in high spirits attended to state affairs and his prime minister dozed in the morning sunlight, drowsy with speculation, the flames were burning too quickly and the fire was too strong.

July 27, 1945

Later that day, an extra edition appeared carrying news of the Potsdam declaration:

In his diary, Leon Ma. Guerrero records how it was an unusually beautiful day; and then, the news of the Allied ultimatum was hinted at:

It was a lovely day in Tokyo today; the sky was a limpid blue, bright and lively with clear sunlight. It was cool for July; agricultural weather experts were worrying in the Times about the young rice. The temperature had not gone higher than 15 degrees; it was really March or early April weather; and the growing rice liked a little warmer sun. But the school-girls in their vegetable patches on the crest of Kudan hill were giggling and pushing one another, their voices high and fresh. A couple of soldiers from the barracks nearby were running after a stray pig; it was a small scrawny pig but it was tricky and elusive and the soldiers, clumsy and ungainly in their new yellow boots, stumbled amid the wreckage of a bandstand with loud excited laughs. In the wide formal park of the Yasukuni shrine visitors from the provinces were eating their lunches under the quiet trees. There was also a group of army clerks stretched silently on the grass. From the foot of the hill came the whine and clatter of streetcars toiling up the slope. It was a pleasant grateful lull in the fortnight of alarms; and the people of Tokyo, the grimy housewives gossiping in the ration queues, the thoughtful students dangling frayed white towels at their belts, the stumbling babies picking at their sores, the clerks and policemen, the technical majors and pathetic drabs, all wrapped in that curious and uniquely Japanese smell of pickled radish, cheap pomade, and soya bean sauce, were chatting and dozing in the sunlight wherever they could find it.

It seemed impertinent to note these things because in a distant German city, one day and half-a-world away, the powers at the gates had announced an ultimatum to Japan. The Tokyo papers hinted at it in subtle innuendoes. A delayed dispatch intercepted by Domei threatened that “immediately following the termination of the Potsdam conference, the Soviet Union, the U.S.A. and Britain are reported to have decided to make a vital joint proposal to Japan. They had no short-wave radios so they did not know but even as they sat in the sweet summer sunlight, the air above these dreamy people of Tokyo was vibrant with a last demand for unconditional surrender. Doubtless in the hidden halls and palaces the warlords were pondering on this message; perhaps even now the ministers of His Imperial Majesty studied one another’s faces with jealousy and suspicion as they debated what course could put the imperial mind at ease. But for this one miraculously peaceful day the mind of the common man in Tokyo was already at ease, in the soothing warmth beside the golden carp that swam silently in the depths of the imperial moats.

July 28, 1945

Tokyo’s dreamful lull did not last long. This morning about 240 P-51’s, led by several B-29’s, raided the Kanto district while some 600 carrier-borne planes were raking Central Japan. Life was once again hurried, stern, tense with dire warning and desperate decision.

July 29, 1945

Japan will ignore the Potsdam declaration. It develops that Foreign Minister Togo reported its contents to the cabinet at its regular meeting on the 28th and that the Japanese government would “say nothing on it”. No one else had anything to say on it. The Mainichi said the proposal was “most insolent” and “based on self-conceit” but neither in its own nor in the other editorial columns was there another word of condemnation, rejection, or challenge…

The mere fact the ultimatum has not been scorned and excoriated outright in the familiar terms of arrogance, contempt, and outraged defiance, betrays the faltering hand, the breaking nerve. The terms, as published, are hard: a naked, prostrate Japan penned up in her rocky islands, a beggar under guard; for the warlords and sealords, disgrace and an unknown punishment. But the alternative is suicide like Germany’s.

It is an electric silence. A decision has not been made by the pale brooding men who must make it or, if it has been made, the words have not been found to announce it. How should ruin be announced? How can suicide be made palatable?

July 30, 1945

From his diplomatic perch in Tokyo, Leon Ma. Guerrero observed the Japanese government trying to remain defiant; but he noted how this defiance was in the face of a very obvious ramping-up of the Allied bombing effort:

Can the Japanese government continue to “ignore” the three waves of carrier-borne planes that attacked the Kanto this morning, or the fleet that shelled Kamamatsu and the Kii peninsula last night, or the 500 B-29’s that set ablaze another constellation of cities on the night before? Pursued by these inexorable facts the generals and admirals must throw behind them a scrap of mendacity, a cheap and flashing trinket of bravado, to amuse and delay the hounds.

The Premier Admiral Baron, waving aside the Potsdam ultimatum as a mere rehash of the Cairo declaration, told the press last night that he was still “firmly convinced of final victory in the decisive battle”. But these were already frayed and shoddy words, their meaning faded by constant use; they were the small change of politics; the feeling remained that they were being traded for time while the big deal was being worked out. Potsdam is a long way from Cairo, as far as Saipan from Okinawa. Tozyo had never seen a B-29 over Tokyo; now Suzuki was talking to the press in his official residence, and not to a scheduled mammoth rally in Hibiya hall, because carrier-planes from a task-force at the coast of Japan had driven him to cover.

Nevertheless the old man had managed to ignore the postponement of his first public appearance as an orator and to reassure as best he could the proxies of his audience. After long delays, he announced, the construction of underground factories had finally been started. “Unusual endeavors are being made in that direction and great expectations can be had for its progress.”

Of course, he admitted, “it is but natural that during the period of transportation of machinery, production should fail to reach the desired figure.” But “efficiency was mounting”. The laborers, men and women, were working 16 hours a day “in absolutely safe areas and in perfect peace of mind. From time to time they were take outdoors and given physical exercise. The air in the tunnels was “not so injurious to health,” he had been told.

At any rate he had made several inspection trips and had found the number of underground factories on the increase. At one such factory “several hundred airplanes” were being turned out every month. The exact figures were secret but “the number is not so small as people may think.” “The other day,” recounted Suzuki,”a certain airman asked me how many hundreds of airplanes were being turned out a month. I said: ‘Why how many hundreds? It is not a question of hundreds but thousands!’”

In case this was not sufficient to distract the people from the deadly dilemma that confronted the country, the General President of the Great Japan Political Association, Jiro Minami, dangled another ambiguous and noncommittal red herring. “It is clear” he told the press, “that a complex intrigue underlies this (Potsdam) declaration. That is most clear in that the enemy is trying to allay war weariness in his own camp and trying to foster as desire for peace in ours.”

Perhaps he was reading his own fears and apprehensions into the designs of others.

He added a story told by a Japanese military police (Kempeitai) officer to the Philippine ambassador, Jorge B. Vargas:

A kempei captain told Vargas today that in his own limited district in Tokyo alone an average of two Japanese spies are being arrested daily. What was more portentious even than their existence was their motive. Usually they were fumbling amateurs with no means of transmitting the military information they had secured or hoped to secure. They were merely “investing” in it; hoarding it for the day when they might trade it for some measure of safety or advantage from the conquering invader.

July 31, 1945

Writing as a diplomat, Leon Ma. Guerrero in Tokyo summarizes the evolution of Japan’s attitudes towards the Soviet Union:

There was a time when the Japanese hoped to win a negotiated peace through the U.S.S.R. Probably about the time of Germany’s fall the foreign office received instructions to make a thorough investigation of Soviet foreign policy. Day and night the red-eyed experts pored over every speech, statement, inspired release, interview, and comment that had come out of the Kremlin since the start of the war. Finally the rather obvious conclusion was reached that the U.S.S.R. could follow three possible courses of action in East Asia: 1) Continued neutrality, which was eventually eliminated by notice of the Soviet Union’s intention to abrogate the non-aggression pact; 2) Entry into the war on the side of the Anglo-American powers at the last moment, in order to claim a share of the spoils; and 3) Positive arbitration of the war in order to enhance Soviet prestige as a peace-lover, a peace-maker, and an arbiter of the world. It was on this third, admittedly tenuous, possibility, that the Japanese pinned their hopes.

He then relates talk in the diplomatic grapevine on Japan approaching the Soviet Union as a go-between in negotiating with the Allies. He was unaware, of course, of Russia’s intention to join the war against Japan. But there were signs Russia was no longer a prospective go-between:

While the Japanese embassy in Moscow conducted the main campaign, the Soviet embassy in its evacuation center in Gora found itself the objective of a supporting action. We who were on the outside saw only slight hints and indications of these negotiations. Prince Konoe, well-padded with carefully groomed flesh, would spend a cryptic week-end at our hotel, 10 minutes by electric tram from the Soviets. A marquis would mention casually that Konoe and he had been treated to such a Czarist display of exquisite caviar and rare wines on the last time they had seen a Soviet newsreel in Gora. Or else a Chinese diplomat would tell with a chuckle the story that the Soviet ambassador, after accepting an invitation to dinner from Prince Konoe, had caught a diplomatic cold and had sent a secretary instead.

These days, however, in the negotiations are still kept a confidential story, it is only in chagrin and discomfiture. Prince Konoe had not been in Hakone for days. The Soviet embassy has no films to show except a newsreel on the fall of Berlin. The ghostly hope that the U.S.S.R. would save the warlords has finally been laid. The Soviet delegates sat side by side with the Chungking representatives at San Francisco. And following the developments at Potsdam with a glassy fascinating stare, the Japanese have seen their misgivings turn to doubts, their doubts to suspicions, their suspicions to apprehensions. There had been first the A1 dispatch, quoted by Domei, that “President Truman had succeeded in obtaining the consent of Marshal Stalin and Premier Churchill to placing East Asian issues at the top of the agenda”. Then there had followed “strong observations” that Truman and Stalin had actually “been negotiating on East Asian issues”. In the end there had come this solemn ultimatum which, though Stalin had not signed it, he must have seen over the shoulders of Truman and Churchill.

“The East Asian issue has entered into a period of decisive advance,” simpered the Asahi on the 27th. “If the report of an agreement on East Asian issues is true, then it must be based on the inevitability of war with the Japan as well as the alignment of the policies of the U.S.A. and the U.S.S.R. regarding the continent of China.” But in this peaceful valley at the foot of Fuji, Japan’s attitude, at least toward the Soviet diplomats in Gora, has not undergone an “adjustment”. From their trim white modern hotel, overlooking the descending hills and the misty sea, they go out every day, with their chunky, flashily dressed ladies, to nod amiably to the awed neighbors the steep streets or to buy a handful of blue pearls and a dozen carnation-embroidered kimono from the submissive storekeeper of the diplomatic shop. They do not bargain.

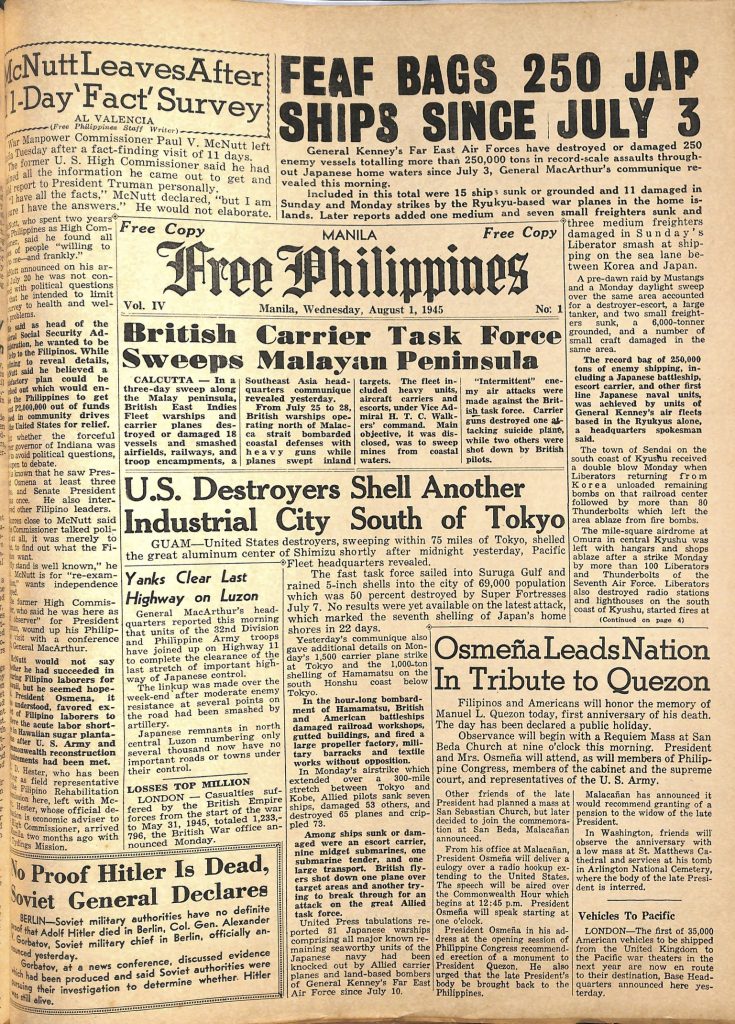

August 1, 1945

Carefully reading the papers for signs of official intentions, in Tokyo, Leon Ma. Guerrero writes that he detects a change in the Japanese posture, towards an openness to a negotiated peace:

The shadowy outlines and decision on the Potsdam Declaration may perhaps be seen in a Domei comment carried inconspicuously in an inside page of the Times today…

There is a faintly exploratory air in this analysis that underlines recent trends. The language is not violent; it is cautious and tentative. The American government, it seems to say, is not having an easy time of it (an echo of Kurihara); it is ready to bargain. The Potsdam declaration, furthermore, is not really an ultimatum; it is a show-piece for home consumption; it is a shrewd trader’s first offer; it can be jewed down. But what can Japan bargain with? It can bargain with its power and will to continue; a bloody resistance, ultimately suicidal and futile it may be true, but one that will require such heavy sacrifices that the Americans, impatient to end the war, frightened by mounting casualties, will be glad to avoid it by a reasonable arrangement.

Into this vague pattern the scattered hints and insinuations of the past few days fit readily. Suzuki’s underground factories and “thousands of planes”, Minami’s “complex intrigue”, the poised and silent watchfulness of the editors, take their places in the still sketchy picture of a deal, to be sprung at the proper time on the simple honest people who are even now preparing to die.

He then attended a Buddhist rally, and in the end, decided to leave early:

I felt this uneasy curiosity following me to a Buddhist rally at the Imperial Hotel for which invitations had been received at the embassy. It turned out to be for the purpose of passing a declaration on behalf of the 50 million Japanese Buddhists. A small banquet room had been arranged hastily as a hall-oratorium. Rows of chairs filled the center of the apartment while along the windows were arranged the heavy overstuffed lounging armchairs with which the place must have been originally furnished. There was an air of hasty improvisation, and perfunctory duty about the whole thing.

It was odd enough in itself that these shaven-skulled monks and gossipy old deacons about me should have been chosen to reaffirm Japan’s will to fight at this desperate crisis. It occurred to me that possibly it was because they could be trusted to speak more credibly and naturally in the gentle accents of sweet reasonableness. The warlords had eaten enough fire.

A couple of quietly dressed and elderly gentlemen were passing around programs and copies of the proposed declaration…

How meek and mild and ineffectual did these men look, their hands folded on their laps, their eyes on the frayed carpet. They looked so bewildered. What calculations of high state politics had called them from their sutras and their rosaries to drown with their mumbling prayers the clang of broken swords?

Foreign Minister Togo was present, as pious as the rest. He looked old and weary; hid phrases were perfunctory; and he hastened away immediately after speaking. The minister of education and the president of the board of information followed; the latter droned on and on for what seemed to be hours.

I could stand it no longer. I was going to tiptoe out. To a colleague I whispered that if any word was asked from our side he could rise and assure the congregation that “all the Filipino Buddhists were heartily behind the declaration.” There are of course no Filipino Buddhists.

For his part, a former member of the government (now in exile) which Guerrero still represented, Antonio de las Alas, reflected on the past. But he did receive some new news, days late:

On this day, Wednesday, August 1,1945 we read that at Potsdam, Germany, Truman, Stalin and Attlee (the new Premier of Great Britain), and with the concurrence of Chiang Kai Shek, sent an ultimatum to Japan demanding surrender. The conditions imposed were that Japan is to have only her four original islands. All lands taken by force must be returned.

August 2, 1945

In Tokyo, Leon Ma. Guerrero noted that Japan finally gave a reply to the Potsdam Declaration:

The warlords gave Japan’s answer to the Potsdam ultimatum at 5 p.m. yesterday. A special communique from imperial headquarters announced that “our army and navy preparations to cope with the enemy’s invasion operations are being steadily strengthened.” The somber implication is that Japan will fight to the end.

But he believed this was posturing:

However the furtive hope of a bargain is not necessarily dismissed. The communique, in going on to summarize losses allegedly inflicted on the Americans last month, may have intended to define Japan’s bargaining position. Admitting “fairly great damage” to cities, factories, aircraft and vessels, and “damage” to air bases and military facilities, IJN claimed having show down 43 large planes (including 29 B-29’s) and 175 carrier-borne planes. In the Okinawa area, from January to July 31, two carriers, one cruiser or destroyer, two destroyers, two transports, and three other warcraft, were claimed sunk. Japanese submarines, it was also alleged, had sunk two transports while three American submarines had been destroyed. Even admitting Daihonei’s figures the totals were not such as to terrify the Americans. Last night more than 500 B-29’s were again over Japan.

But it’s important to note, in light of what was to follow, that at this point, the Japanese still believed they could drive a hard bargain by actively resisting an expected Allied invasion:

Nevertheless the choice seems to have been made. If the Americans persist in the Potsdam declaration which, according to the Mainichi today, “goes much further than what an ordinary victory would entitle a party to in war,” then the Japanese will “steadily strengthen” their preparations against invasion. On the other hand an unspoken alternative remains: if the Americans wish to spare themselves the sacrifices of an invasion, then they might content themselves with the fruits of an “ordinary victory”, whatever that may be.

He closed his entry with an enlightening conversation:

Wondering once again how the Japanese felt about this choice that had been thrust upon them, I remembered a conversation with a young Japanese diplomat a month ago. We had been chatting over a midnight cup of bitter yellow tea in a narrow hotel room and it was almost time for bed. I had not seen him for more than a year and we had had many things to talk about.

On an impulse I asked him: “What do you think of the war?”

“I think we have lost it,” he answered.

“So you would be in favor of Japan making peace?”

“No,” he replied unexpectedly.

But if Japan has lost the war, I expostulated, what was the use of fighting on?

He studied me quizzically, a good-looking young man with black hair brushed back neatly.

“Oh, I see,” I fished. “You believe in bargaining, in fighting on for better terms.”

He gave a deep chuckle. “No, that is what the army is doing. That is what they have been doing for the past two years. No, I want the war to continue because the people haven’t suffered enough.”

“Not enough?” I protested.

“Not enough,” he said with a gesture of inexhorability. “Let them suffer. Let them learn what it is to start a war. Let them learn so hard that they will never start another war. Then we Japanese will really have something. We will be ready then to kick out these army bastards and build a good Japan.”

He made sense to me then, good hard cruel sense. Sometimes he still does.

August 3, 1945

Once again, Leon Ma. Guerrero provides a snapshot of a Tokyo –and Japan– committed to expecting a massive Allied invasion:

In this breathing-spell before invasion, it is strange, looking around, to see how imperceptibly and yet how inevitably these people and their country, through the small gradual deteriorations of every day, have come to the edge of the pit. One scarcely notices from one week to another, even from one month to the next, how greatly things have changed; how one almost never sees a pretty girl anymore these days; how tired and red-eyed the men are in the trains, the choking trains where shabby bristly men fall asleep on the shoulders of the stranger next to them; how one has grown not to expect the fish and vegetable rations, how many smokers wait patiently for a fortunate passerby to strike a rare matchstick.

But it is a society deeply hungry, even as every able-bodied citizen receives summons to join fighting units:

I note at random that the wife of a German I know surreptitiously eats handfuls of pine-needles from the hotel garden “because they are full of vitamins, you know”; that a pound of butter costs 120 yen; that one can get a hand-knitted sweater for five tins of jam or marmalade; that one excellent American noiseless portable typewriter is being offered for 2,000 cigarettes; that a marquis and a viscount, prosecuted for smuggling out platinum, have returned their titles; that street-vendors in Tokyo have been ordered to take shelter even during a precautionary alarm because of the single raider that dropped a bomb midtown the other day; that, possibly for the same reason, the long queues before the movie houses have disappeared.

The papers report that the vice-ministers have asked the people to gather five million koku of acorns (on koku is about five bushels) “to be turned into food”.

Ships’ crews have been organized into a “volunteer fighting corps of their own under the navy.

Meanwhile, the air attacks from Allied bombers continued to increase:

Writing in the Asahi the head announcer of the Japan Broadcasting Corporation says that “air-raid broadcasts have increased in number. In the beginning there were only two or three air-raid broadcasts concerning a single enemy plane but this has increased to 30 on the average. There was one air-raid broadcast every two minutes when enemy deck-planes raided Japan on the 10th July. The air-raid broadcasts totaled 300 and lasted for 10 hours at a time.”

Another paper reveals that Viscount Keizo Shibusawa, governor of the Bank of Japan, had opened up his private residence in Shiba-ku, Tokyo, to 37 homeless air-raid sufferers since April. He first took in nine assistant police inspectors. Later were added a high bank official and his son, three office girls, a shipyard manager and his girls, one dressmaker, four officers, the widow of a military man, five schoolboys, three maids, and the entire family of the steward. They all eat together and have access to the viscount’s library. “All the members of the household,” the news-story says, “have certain duties allotted to them. For instance, the nine assistant police inspectors are responsible for air-raid defense, the three maids cook, the widow distributes rations, the steward and the schoolboys take care of the truck-garden (converted from the tennis court and lawn).” Nobody knows what the officers do.

Step by step, one gets used to things from which a year ago, the Japanese would have shrunk with repugnance: living in a damp trench under a sheet of rust iron; drinking peanut juice “as white as milk”; sleeping uneasily in their working clothes. If the warlords’ bargain falls through, they can all presumably accustom themselves permanently to being dead.

August 4, 1945

Leon Ma. Guerrero recounts the experiences of a population subjected to constant air-raids:

A number of Filipino students were returning home the other day when their train was strafed. An Indonesian with them was killed outright by a bullet through the head; one of the Filipinos was hit in the arms and thigh and may have to undergo an amputation.

Two of our other students were luckier. Coming back from the south they were under constant air-attack but escaped injury, once by diving under the wheels of their railway carriage. Railways and ferries were in total confusion, they reported. The trains were crawling by fits and starts through a land in flames or in ruins.

August 5, 1945

In his diary, Leon Ma. Guerrero tells hunger stories:

The director of the Catholic school in Gora confessed to me that they were living on a day to day basis. What made things worse, he said, was that most of the members of his community were over 60 and received less rations than the ordinary man. He is not fooling himself; he has already bought a cemetery patch nearby.

The Japanese press itself has no illusions. Concluding a series of articles on the war the Yomiuri declares that “frankly speaking, the future of the food problem is very serious.”…

The Yomiuri also thinks it strange that mulberry trees should still cover enough land to grow six to seven million koku of sweet potatoes and wheat. “There can be no question of clothes at a time when there is about to be no food.”

“All in all,” the Yomiuri summarizes it up, “the food problem lies in the psychological attitude of each and everyone in the country. Some persons say that they cannot fight on an empty stomach. But they are the ones who would not be able to fight on a full stomach either.”

August 6, 1945: First Atomic Bomb dropped on Hiroshima from a B-29 flown by Col. Paul Tibbets.

After leading off its Potsdam story two days ago with the observation that the Big Three “failed to produce anything that has direct bearing on the war in the Pacific”, the [Japan] Times today front pages the British foreign office statement on the war against Japan, including the official comment that “it is impossible to draw the inference from the communique that Russia will not enter the war against Japan.” It is the first time I have seen it openly and directly admitted in the Japanese press; so far editorialists have talked obliquely of “chance of attitude”.

August 7, 1945

In Tokyo, Leon Ma. Guerrero recorded initial reports about the dropping of the atomic bomb on Hiroshima:

The San Francisco radio announced today that a new “atomic” bomb had been dropped on Hiroshima yesterday the 6th, wiping out 60 per cent of the city at one blow. Apparently the bomb is built on an entirely new principle, the splitting of the U-235 atom. From another viewpoint, the principle is as old as war, mass murder.

But if we do not know much about it, and do not know how much to believe of what we have heard, the ordinary Japanese knows so little that he does not even seem to care. A brief communique from imperial general headquarters, issued at 3:30 p.m. today, reads in full:

“1. Due to the attack by a small number of B-29’s on the 6th August considerable damage was caused to the city of Hiroshima.

“2. In conducting the attack the enemy seems to have used new-type bombs. Details are now under investigation.”

Just as interesting was his analysis of the seeming indifference of the Japanese public to the news:

The man in the street cannot be blamed if he sees nothing particularly alarming about that. “Considerable damage” is several notches above the usual “negligible”, “very slight”, and “slight” but it is still below the occasional “heavy”. “New-type bombs” is vaguely disquieting but the Japanese are still sufficiently naive, scientifically speaking, to take even the splitting of the atom for granted. It is a curious novelty, like an electric torch, but these things are always happening in the strange surprising world of modern times. What will these “new-type bombs” do? We are forbidden of course to discuss with the Japanese the information we receive by short-wave. But I could not resist asking the boy who mops out our bathroom the same question: what did he think these “new-type bombs” were like? He shrugged his shoulders. He had not thought too much about it. Then, head cocked to one side like a little bird, he said: “Well, maybe they kill a hundred people instead of 10 or maybe they burn concrete houses like wood. I don’t know.” He bowed and sidled out, leaving me to wonder if he cared at all.

August 8, 1945: The Soviet Union declares war on Japan.

In Tokyo, as Japanese officials scrambled to comprehend the atom bomb, Leon Ma. Guerrero recorded nearly in real time, the details of the Hiroshima bombing being pieced together:

The details of the new bomb are still “under investigation”. One feels that the authorities are just an puzzled and bewildered by the whole thing as anybody else; they are certainly withholding the extent of the damage but do they know any more than the average man about the nature of its cause? was it one bomb or several? Was it an incendiary bomb, an explosive, a combination of both?

The first accounts in the local press are cautious…

The Americans have announced that leaflets have already been dropped warning the Japanese of the new bomb’s unprecedented destructive power and the Asahi ends its story by calling on the people “not to be misguided”. Perhaps in preparation for an official declaration on the bomb the Times today, which has not yet carried a story on Hiroshima..

After extensively quoting Japanese editorials on the differences between the West and the East in making war, Guerrero reflects,

There is an exasperating emptiness to these eloquent and elegantly-balanced phrases. It is like listening to a professor belaboring a syllogism while the classroom burns. The man is splitting hairs when a bomb is splitting atoms. Perhaps a year of a hundred years from now philosophers and historians will have the perspective to weigh the relative values of Western science and Oriental spirit. Right now we are more interested in what will happen to us, whether it is safe to take the train to Tokyo tomorrow, whether the new bomb will poison water, whether peace will come.

I know I should be thinking of the implications of a bomb that can wipe out two-thirds of a great city at one fell stroke but somehow the mind refuses to pick up the problem and it lies at my feet ticking with a quiet insistence. The question of peace is the farthest that the mind will reach. Some say: “It’s over. The Japs will have to give up.” Others are not so sure. They mumble about exaggerated propaganda or they cry in despair that the Japanese are crazy; they will die rather than surrender. To them the measured cadences of the Times editorial today have the sinister sound of a man walking to the gallows.

Yes, the Japanese will stick it out, they say. They will burn in their cities, disappear in a sickening flash, and then the gaunt roasted survivors will dig in, in the caves and crevices of mountains, by a last lonely beach…

And Guerrero reflects that the horrifying questions posed by the war makes people seek refuge in trivial details:

Psychological speculation is scant comfort for those of us who are caught here between scientific murder and a suicide complex. Presently the tight groups, heatedly debating peace and war, break up; the mind, frightened by its own reflections, scurries away to its favorite corner and toys with the familiar commonplaces of the day’s paper. Let us see now….

The Japanese army in the southern regions has announced its “assent to the establishmnt in the middle of August of a preparatory commission for East Indian independence.”

The cigarette ration has again been cut from five to three per person per day. In case the production of cigarettes becomes impossible the equivalent amount of cut tobacco will be supplied.

A certain factory in Nagano prefecture has succeeded in producing a substitute for Manila hemp from dwarf bamboo creepers; it is cheaper by 20 yen a pound.

A group of scholars has called for donations of materials for an Okinawa museum and library in Tokyo.

Real summer has started, according to the papers. The rice is flowering about 20 days behind schedule but the rising temperature during the past week may save the situation.

(It is pleasant out here in the garden by the miniature waterfall, sparkling and laughing as it tumbles over, while the red, black, and golden fish wheel silently in the quiet pond.)

Let us see now… The classified ads are always good. Wanted to exchange: bicycle, foreign make, 22 inches, in good condition, for men’s shoes, size 10% men or larger size.

For sale: a set of sofa and three armchairs; easel, almost new, in perfect condition; gentleman’s white linen summer suits and also one white waistcoat; Nippon Gakki upright piano, 85 keys; Vacumatic Parker fountainpen, for immediate sale to highest bidder, also ivory mah-jong set.

Wanted to buy: baby’s perambulator, shoes for girl 5-8 years, linguaphone language series for Russian and others, English books on China, razors, sewing machines, accordions.

(The mind drowses contentedly. Whatever happened to that gentleman who was selling shirts, three white second-hand, two black perfectly new? I wonder what they will serve for lunch…)

Back in Iwahig, Antonio de las Alas reflected on the other historic development of recent days: the defeat of Winston Churchill in the recent British elections:

We learned of the defeat of Premier Churchill of Great Britain by Clement Attlee, a Laborite. Politics is certainly a most ungrateful game. It was Churchill who saved Britain. If it were not for his indomitable spirit, his determined will to fight, Britain might have succumbed. But people or the electorate is fickle. The same thing happened to great Clemenceau of France after the First World War. Wilson died disappointed because the United State Senate turned down his League of Nations.

August 9, 1945: U.S. Drops Atomic Bomb on Nagasaki; Emperor Hirohito convenes Supreme War Council; Soviets invade Manchuria

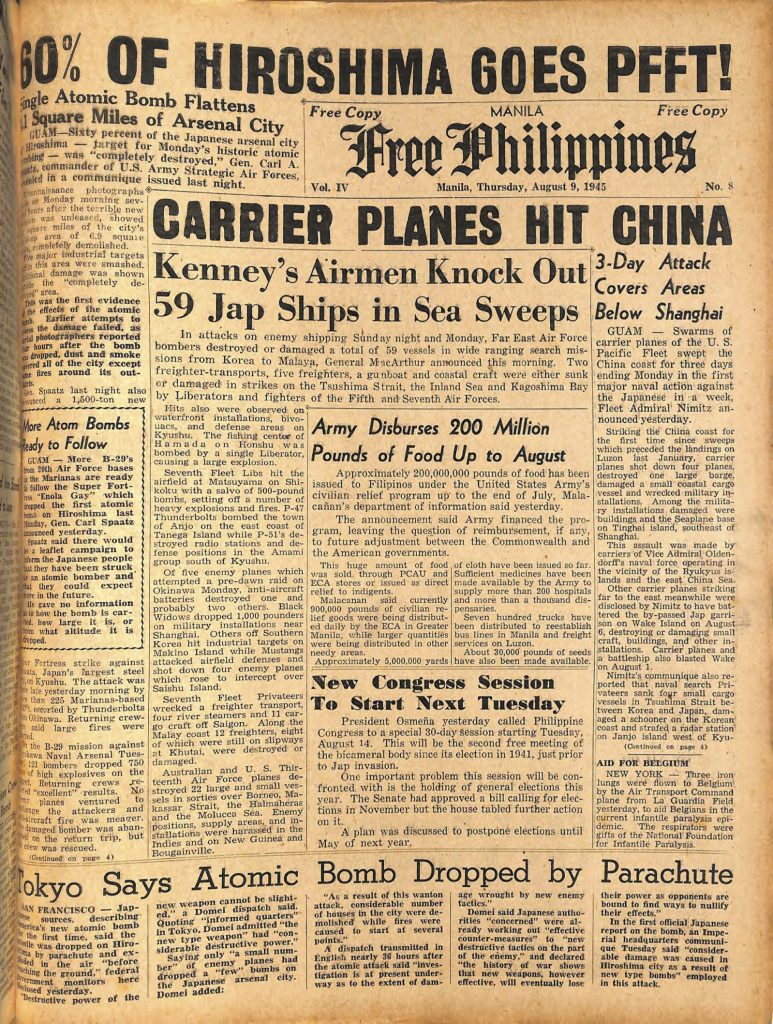

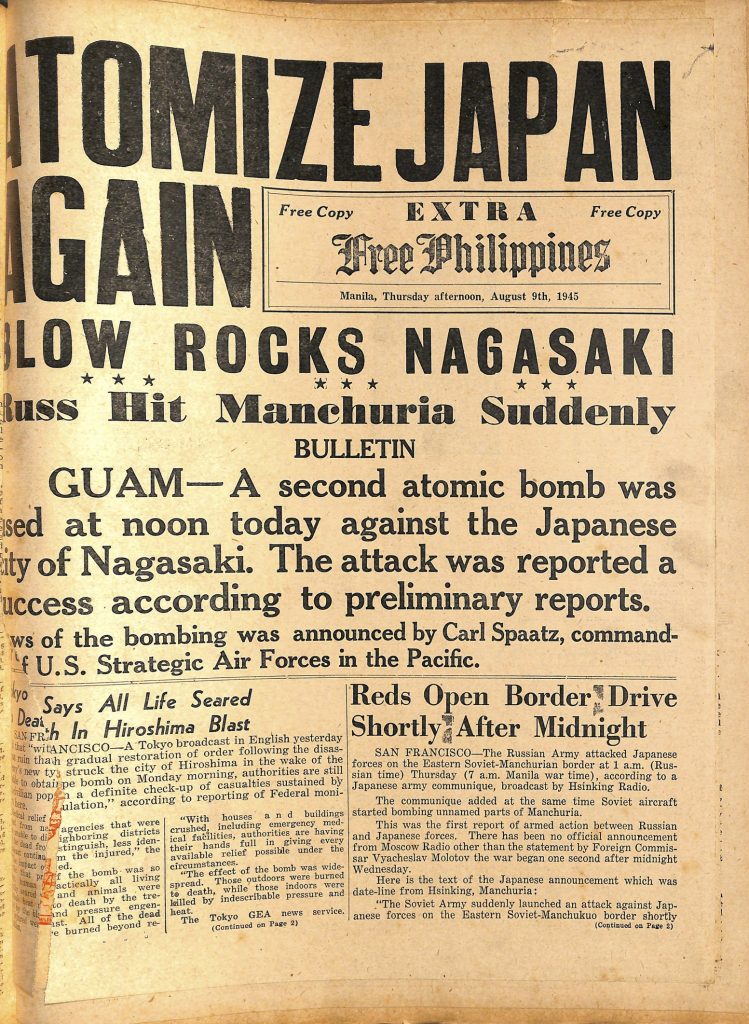

An extra edition with news of Nagasaki:

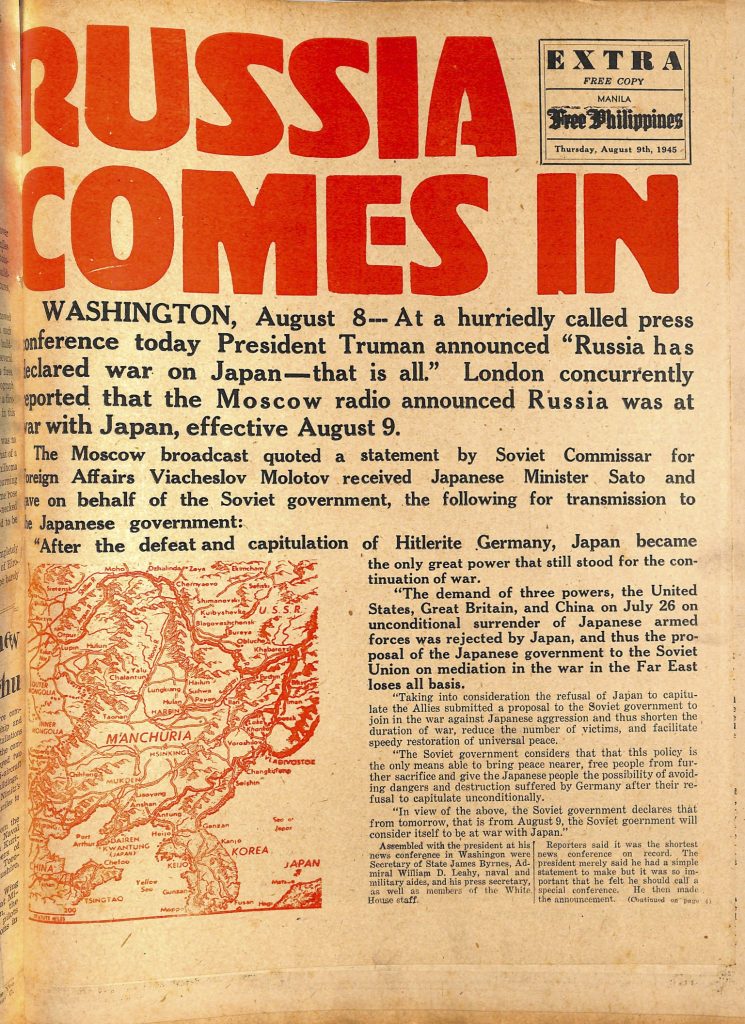

And yet another extra edition with news of the U.S.S.R. entering the war against Japan:

Even if far away from the center of events, the Iwahig Penal Colony was up to speed on the big news, as Antonio de las Alas recounted:

Big News. Russia declared war against Japan. This is now practically a war by the whole world against Japan. Taking into consideration the military strength of Russia, the Pacific War cannot last much longer.

For the first time the Americans dropped in Hiroshima, Japan, an atom bomb. Its destructive power is beyond classification. It is said that it is equal to bombs thrown by 2,000 superfortresses. It kills everything and lays waste an area covering a radius of seven miles.

With Russia’s entry and this new bomb, Japan will have to surrender.

For his part, Leon Ma. Guerrero, with his information from the diplomatic grapevine, knew at once of news of the dropping of a second atomic bomb on Nagasaki:

As San Francisco announced that the second “atomic” bomb had been dropped on Nagasaki shortly before noon, the vernaculars started to open up a little on the subject. It seems that “the authorities of the various government departments concerned have dispatched officials to the scene of destruction.” “According to a survey made, the new-type bomb drops toward the ground with a parachute and issues a strong light when the bomb is about 500 to 600 meters above the ground and then explodes. Simultaneous with the explosion, a large detonation is heard and a strong blast and strong heat accompany it.”

“Full caution,” warns the Asahi, “is considered necessary but it is pointed out that in case or a new-type weapon, its effects are usually exaggerated. For instance, when the V-1 made its appearance, considerable confusion and disturbance were Witnessed in England before counter-measures were devised. Upon completion of the counter-measures, the composure of the people returned.”

Guerrero then wrote in exasperation over the feeble advisory from the authorities on how to respond to the dangers of atom bombs:

What counter-measures were contemplated against this “new-type” bomb?The Asahi also published a statement of the air-defense headquarters giving directions as to the methods of defense against it…

There is almost a touch of the sinister in this stupidity. Get into a trench and pull a blanket over your head — but don’t forget to put out the fire in the kitchen! It is impossible to believe that air defense headquarters really thinks a blanket and possibly a pair of gloves can ward off the gigantic flame that dissolves an entire city. It is more reasonable to see in these “directions” a deliberate attempt to assuage the alarm of the people; if that is all that is needed, then the new~type bomb is just a bigger incendiary which burns people as well as houses. There is authentic art in that artless reminder not to forget the kitchen fire.

How long will the Japanese continue to believe it? When they learn the horrible truth, will they rise at last to cry enough or will there be anyone left to rise?

And yet, what could the authorities have said? What defense is there against this new “atomic” bomb? Tonight we were discussing heatedly the relative protection afforded by a swimming pool and a deep cave. But what was there to say? We did not even know whether the bomb killed by heat, by concussion, by radioactive radiations, by gas, or by some other terrifying mystery of dissolution. A blanket over the head seemed just as good as anything else.

But there would be another bombshell, news-wise, left for that day:

Then just before dinner some of the evacuated Japanese school-children in the village ran up to a Burmese cadet with whom they had made friends. They were laughing with excitement. There was a new war. The radio, they said, had announced at five that afternoon that Soviet Russia had declared war on Japan. We flicked on the short-wave radio. San Francisco confirmed it.

Somebody laughed. “We won’t have to worry about that new bomb anymore. It’s all finished.”

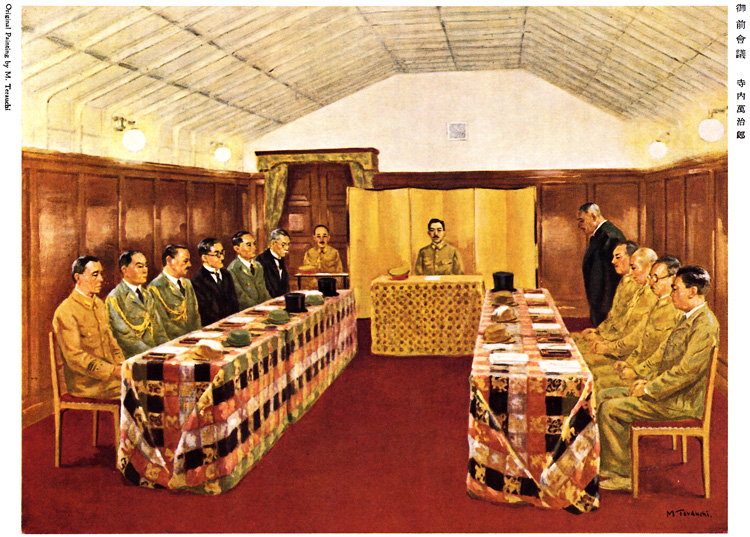

Late that night, the Emperor of Japan met with the Supreme War Council in an air raid shelter in the Imperial Palace grounds. The moment of final decision had come.

Imperial Conference of 9-10 August 1945

(painting from Reports of General MacArthur)

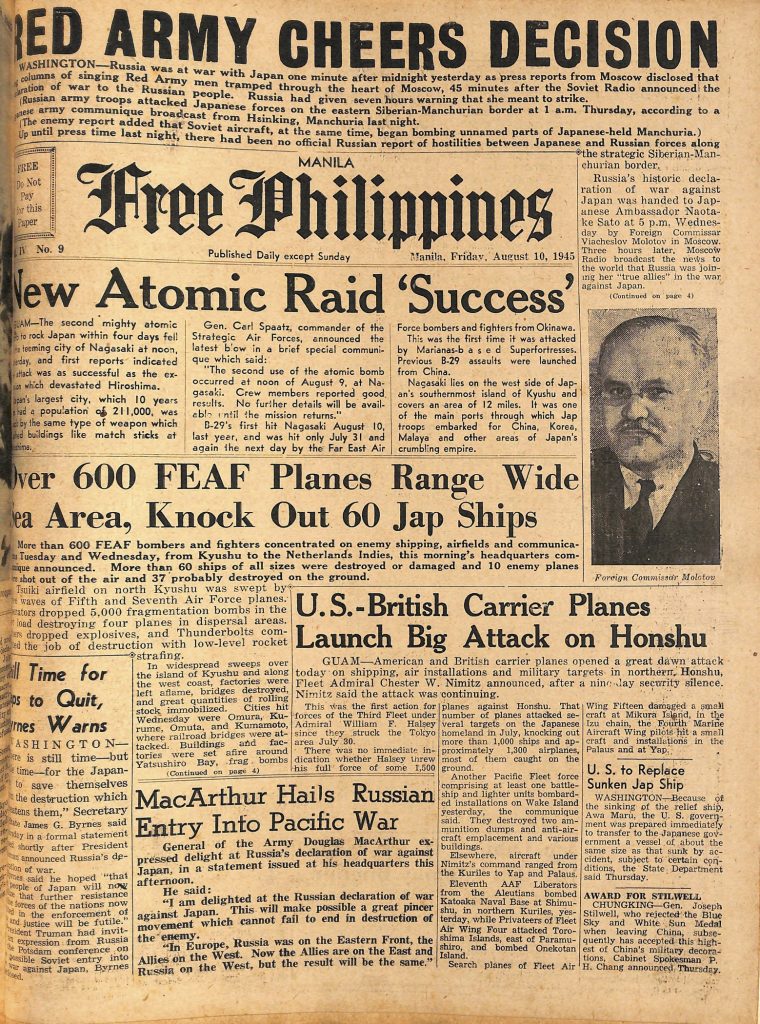

August 10, 1945

In Tokyo, Leon Ma. Guerrero recounts the reactions of diplomats to news of the declaration of war by Russia on Japan:

The Soviet declaration of war has thrown this diplomatic hideout into a turmoil even louder and more confused than the new bomb. Even those who doubted the persuasive powers of the atom have thrown up their hands. Nobody seems to doubt now that Japan is doomed. The only questions are when and how. Will it be in a week or by spring? Will Japan surrender formally or will she commit national suicide? when these questions are finally answered by events, the solution will appear inevitable; it will seem to those who look back that they should have seen it all the time, that the signs were always there for anyone to read. But now we are still in the forest; there are cryptic marks blazed on the tree-trunks, footprints losing themselves in a tangled thicket, wild unintelligible cries that call to the unseen.

Puzzled and uncertain about the future, we can only look back a little distance along the way we have already come. The diplomats especially, the professionals of power politics, feel easier when they can rake over the dead leaves of mistakes that do not matter any more. Look here, if the Japanese had not forded this river here or if they had gone forward along that valley… A German diplomat insisted on explaining to me where Japan had made a fatal error about the Soviets. If the Japanese, he argued, had accepted the German proposal to join the war against the U.S.S.R. in 1940, the fate of the Axis would have been different. Now Japan had to fight the Anglo-Americans and the Soviets singlehanded as Germany had done and where was that precious non-aggression pact now?

There’s time for a blame-game between Axis allies, too:

Then a Japanese diplomat took me aside. “The Germans blame us,” he complained, “for attacking the U.S.A. and bringing the Americans into the war. But we are more inclined to blame the Germans for attacking the U.S.S.R. The trouble with the Germans is that they have always been obsessed by fear of Russia.” He sighed and concluded: “Basically the trouble with the Axis was that Japan and Germany could not agree on the enemy.”

In this angry exchange of recriminations nobody seemed to remember the Japanese people who, after all, would perhaps have a say on the matter. All the newspapers had carried in full the Soviet declaration of war with its bland revelation that the Japanese government had actually asked for Soviet mediation in the war.

How were the people taking this hint that the imperial land might be conquered after all, that the Son of Heaven might sue for peace? There was the impact of an “atomic” bomb in the suggestion. For that was all the Japanese had left now: their blind faith in an unconquerable divine destiny, one last faithful ally against the world, one last cave in an earth laid desolate, an old familiar blanket against the cataclysmic flame of a new age.

And then, Guerrero tells human stories as everyone recognizes Japan’s survival is even less likely now that Russia has entered the war:

Stories began to be told in that chattering circle of foreigners. They were cruel sardonic stories, the type of stories that foreigners always tell about the countries they happen to live in, the type of stories that white men in particular like to tell about “natives”. But through the air of amused superiority, tinged with a resentful uneasiness, I could not help but see a strangely appealing picture of this odd fairy-book people, these shabby clumsy and withal gallant peasants with their fantastic readiness to die for a legend, a romantic lie. For that is what the stories told.

Last night, after the news of the Soviet entry into the war, the manager of the diplomatic dry-good store in the village came roaring into the hotel. He was fighting drunk, this small rather conceited corrupt merchant, He and 30 million other Japanese, he cried, were ready to die rather than see Japan surrender. If the worst came to the worst, he wept, he would kill his wife, his children, his neighbors, and any foreigner, any bloody foreigner, who happened to be around. And then he would cut himself open. They all laughed at him and he went to sleep; somehow it was comic to imagine him with his entrails spilling over his shoddy pearls and fake curios.

Earlier a maker of tofu (bean-curd) had been teaching a foreigner how to make charcoal. They got to talking about the new-type bomb and the foreigner asked him what he thought of it. He was a slow conscientious worker and he did not stop puttering about the fire. What was he to say? Well, he decided finally, it was like this. He was an expert maker of tofu. Many foreigners had asked him to teach them the secret of the process. Not all the professors across the seas had ever succeeded in solving it. Now, if these foreigners could not even make tofu, how could they make a bomb that was better than the ones the Japanese make?

There was a visiting manicurist in the hotel, a devout and chatty old woman who had gone to pay her respects before the emperor’s palace every day of her life that she had been in Tokyo.

What did she think, somebody had asked her. would Japan be defeated? She did not think it possible. But the Americans had a new and terrible bomb, the Russians had entered the war, the Japanese where fighting the whole world. Even then, she insisted. The Tenno was divine and he would not abandon his people. Her faith was not so noisy or belligerent but would she be any more eager for surrender? In the face of this determined romanticism, our hopes of the night before for a quick peace, a formal surrender, seemed to shrink and shrivel up.

In far-off Palawan, the Iwahig Penal Colony was abuzz with rumor that a big announcement was forthcoming, as Antonio de las Alas recounted:

Lt. Hagonberg came this afternoon to say that the radio had announced MacArthur was going to speak about 7 o’clock. He was expected to make a very important announcement. Naturally, we became very anxious as we expected MacArthur to announce the termination of the war. After 7 o’clock, we were all outside, anxiously waiting for the return of the Lieutenant. At eight, he had not come; at nine, he had not arrived. Disappointment could be seen in the faces of all of us. Ten o’clock signal sounded and the rule was we had to go to bed and put the lights out. We went to bed, but nobody slept. We were still waiting for the Lieutenant. Whispers could be heard — maybe the news was bad, and that’s the reason why the Lieutenant did not come. At 10:30 we heard an automobile coming. We all jumped out of our beds very excited. It was the Lieutenant. He drove the jeep slowly and walked towards our quarters slowly. He did not seem very happy. We also assumed a serene attitude, not unlike the countenance during funeral services. Before he could speak, many of us instinctively asked him for the news.

He spoke slowly and seriously. He told us that the radio announced that Domei, the Japanese International News Service announced that Japan had sent notes to the United Nations, through Switzerland and Sweden, accepting the Potsdam ultimatum. To us this is very important news. We all felt happy. We could not sleep the whole night — we were too excited.

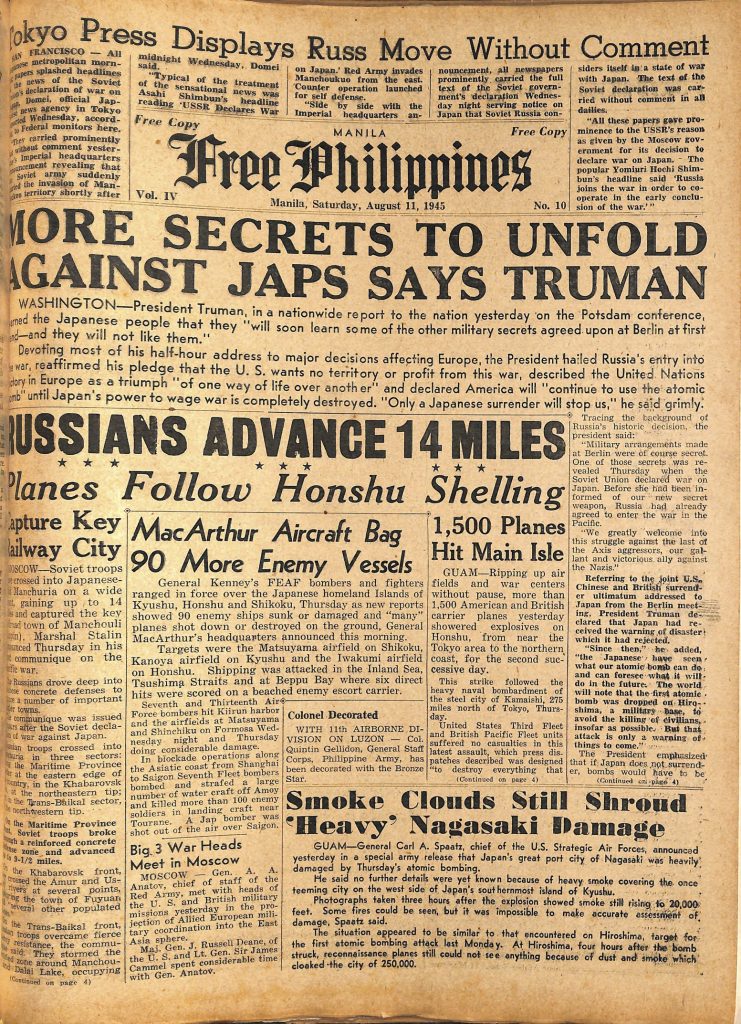

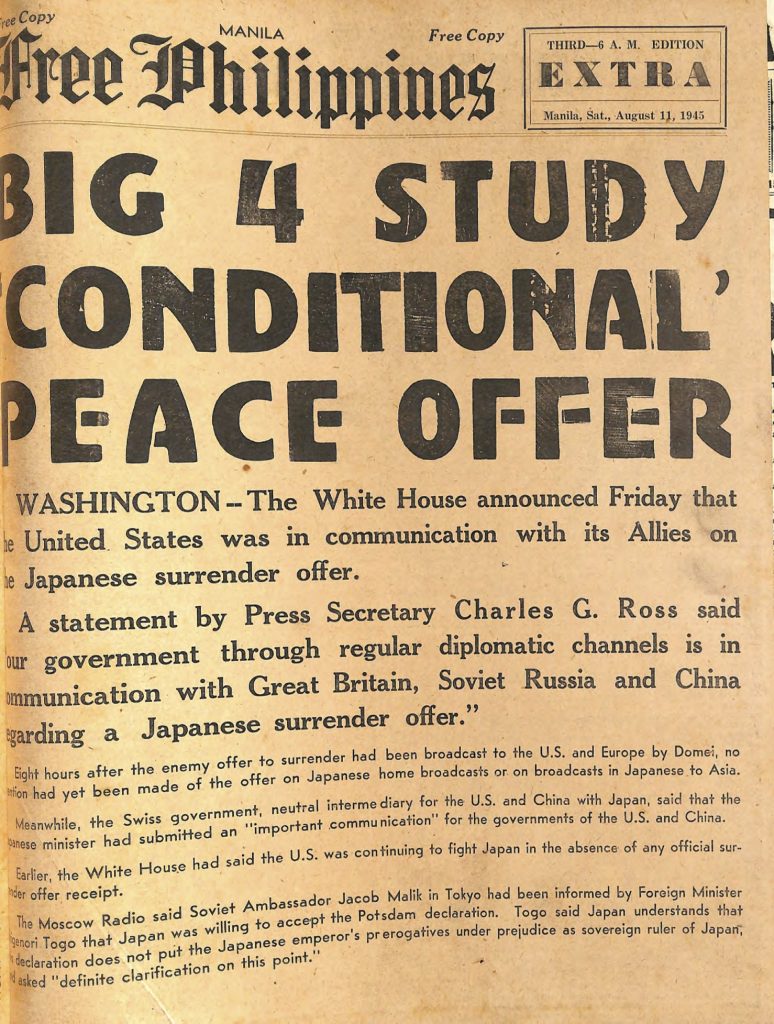

August 11, 1945

An extra edition for that day:

The day began with Leon Ma. Guerrero going to see how Soviet diplomats were doing in detention:

I sneaked up to Gora today to see how the Soviet diplomats were getting along._The village itself was quiet; the streets were almost deserted; the front yard of the hotel where the Russians have been interned was silent and empty; there was not a policeman in sight. The Hakone mountains had never seemed so far away from the war.

But the main event of the day was a rumor spread by a Burmese diplomat:

Then after lunch the Burmese military attache abruptly told us that Japan had sued for peace. We could not believe the news. And when San Francisco confirmed it, hour after hour, we subconsciously protected ourselves from disillusion by worrying over the condition attached by the Japanese government, namely, that the prerogatives of the emperor as sovereign would not be impaired. Would the Americans reject the condition as against the Potsdam declaration? On the other hand, would the Japanese sacrifice their emperor for peace? Once again we tugged and pulled at the puzzle, with the exasperated feeling that the answer was already known.

The Burmese military attache thought that perhaps the Japanese had purposely put a condition that would at the same time appear reasonable and yet be unacceptable in order to solidify public opinion at home and divide it abroad. The suggestion did not sound far-fetched. The emperor was eminently the one condition on which the Japanese could agree, the one condition for which they would all be ready to perish. He was also one condition which could be calculated to divide the Americans who believed so passionately in leaving other people alone to choose their own form of government. What a masterful intrigue if it were true!

It was only on this day, that the Japanese press reported the effects of the atomic bomb on both Hiroshima and Nagasaki:

But the new bomb floated ominously over these intricate and subtle calculations; what did the cunning of diplomatists and the fanaticism of peasants avail against this imponderable atom dangling from its parachute? While the air crackled with its secret offers, the vernaculars published today the first eyewitness accounts of Hiroshima. The Yomiuri, which also noted briefly that another “new-type bomb” (in the singular) had been dropped on Nagasaki on the 9th…

…Presumably on the basis of these first-hand experiences the air defense headquarters has issued further instructions on how to deal with the new bomb. There is a frantic reiteration about them that borders on hysteria.

“1. It is very effective to seek safety in an air-raid shelter. It is necessary to repair and strengthen shelters which are covered.

“2. In regard to dress, one should expose as little of the body as possible. Otherwise one will suffer burns.

“3. The use of an air-raid-defense hood and gloves will prevent burns in the head, face, and hands.

“4. If there is no time to seek safety in an air-raid-defense shelter or if there is none in the neighborhood, one should lie flat on the ground or utilize a solid building for protection. But it is important to seek safety in an outside shelter.

“5. If the above points are remembered together with thos -previously announced, the new-type bomb will not prove to be so powerful.”

Meantime the Japanese government has filed a protest against the use of the bomb. The note was sent through the Swiss yesterday. Possibly it is important for the record. At any rate the Japanese can get from it their first accurate idea of the new bomb.

In Iwahig, Antonio de las Alas notes,

White House in Washington confirmed that a surrender offer had been received from Japan. The news of the previous day came only from a newspaper service. It was not official. Now this is official. Washington intimated that they were in communication with England, Russia, and China.

August 12, 1945: Emperor Hirohito orders his government to prepare a document accepting surrender

In Tokyo, Leon Ma. Guerrero recounts rumors –and the growing sense that despite the fierce rhetoric, a note of what is to come is already being sounded:

All the world knows that the Japanese are ready to surrender except the Japanese, A rumor ran through the Village today that Japan had made peace with the U.S.S.R. but it did not go further. A proclamation issued by the war minister on the 11th notified the army: “The only task before us is to fight out the holy war resolutely for the maintenance of the divine state. Even though we may eat grass, gnaw earth, and sleep on the fields, we shall definitely and resolutely fight. When we do so, I am confident, there will be life even in the midst of death.”

The people know no more. The papers still maintain the atmosphere of unrelenting war. The comuniques follow one after the other: “fighting is proceeding” in Manchoukuo, Chosen, Karafuto; the air force has attacked the American task force in the waters east of Miyagi prefecture; hundreds of B-29’s and carrier-borne planes are blasting Kanto, Chiba, Ibaraki, Tokushima, Kainan, Hachinoye, Misawa, Ominato, and all of Kyushu. The government is studying the conversion of tea leaves and mulberry leaves into a vitaminized flour; 20 girl employees in Karafuto are donating their spare time to the manufacture of salt; the sake output has been increased; benzine is being wrung from pine resin; four railway employees at Yamakita have been awarded prizes for safety maneuvering a burning freight-car full of explosives into a forest before it blew up.

But the announcement of the president of the board of information on the same day as the war minister’s proclamation had already a Delphic note. “The worst condition has now come,” he said. “To defend the last line, to protect the national polity and the honor of our race, the government is exerting its utmost efforts and at the same time expects that the people will also overcome the present trial to protect the polity of the empire.”

In the Iwahig Penal Colony, a phoned-in rumor had detainees like Antonio de las Alas celebrating the end of the war, prematurely as it turned out:

After Mass and breakfast, while I was inside our quarters, pandemonium broke out down below. Everybody was jumping and yelling, “War is over!”. We all went down to join the celebration. I noticed that everybody had tears in their eyes — probably because it meant the triumph of liberty, democracy and justice, but at the same time reminding us that we had suffered, were still suffering as a result of an injustice; probably because it meant our early liberation — we will soon be out to see our dear ones. How many nights have we spent crying, remembering the wife and children we left behind. The rejoicing continued for one hour. When all had calmed down, we inquired where the news came from. I turned out that somebody had telephoned the news to the guard and it was the latter who transmitted the news to us. This did not dampen the rejoicing, however. We were anxiously waiting for the Lieutenant because we thought that if the news were true, he would hurry to communicate the news to us since he had been showing undue interest in our welfare and liberation. When the whole day passed without the Lieutenant making an appearance, we began to doubt again. It was the first time that he did not come the whole day. But we never lost hope, we still believed it was true.

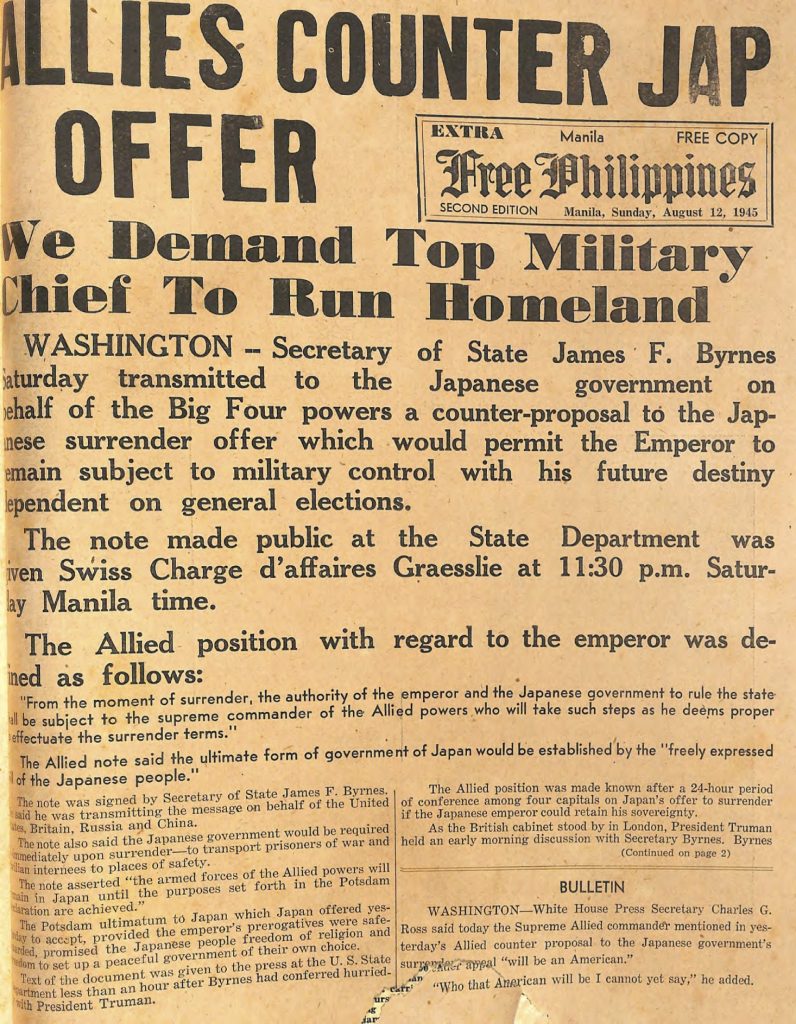

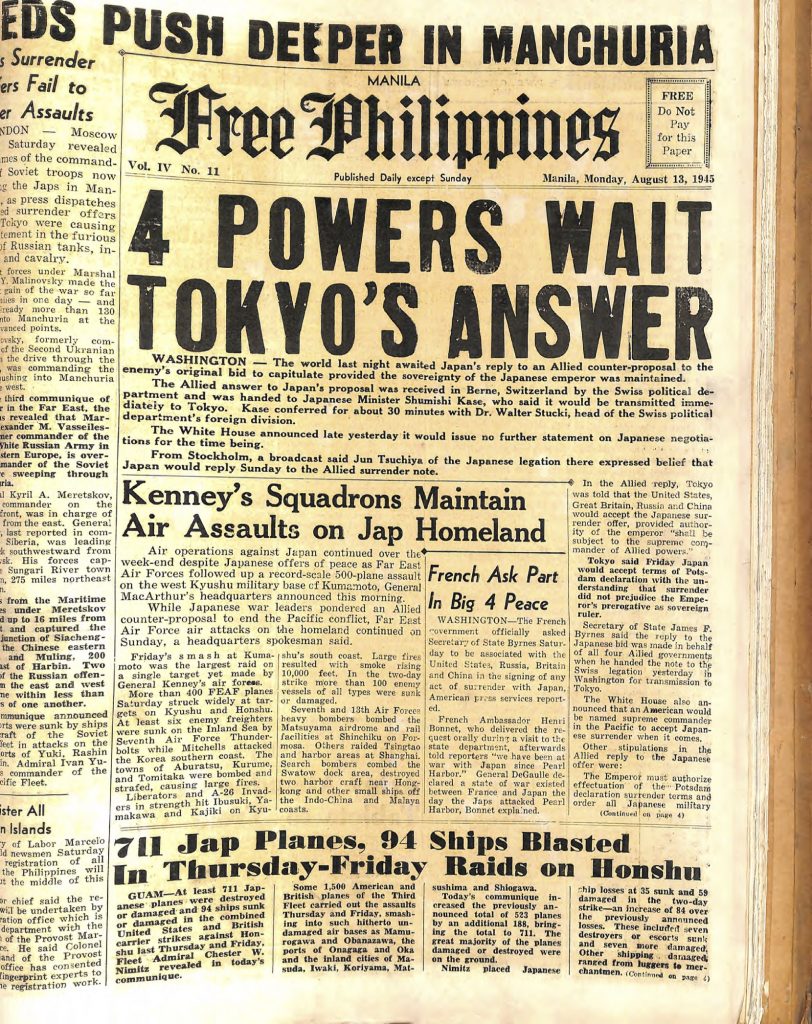

August 13, 1945

In Tokyo, Leon Ma. Guerrero records news as it reaches the diplomatic grapevine, a day late in many instances:

The American reply to Japan’s peace offer has been announced by San Francisco. Delivered yesterday the 12th it demands that the authority of the emperor and the Japanese government be subject to the Supreme Commander of the Allied Forces, presumably General of the Army McArthur. The question is more alive than ever: will the Japanese accept? The tone of the San Francisco bulletins which, with monotonous insistence, emphasize every hour that MacArthur will be the emperor‘s “boss” should warn the Japanese leaders what they can expect.

He also recounts what his fellow Asian diplomats were saying, as well as the possibility the state-controlled media was dropping hints to prepare the public for a possible forthcoming decision:

A Burman wondered why the Japanese, if they were really ready to surrender, had made an issue of the emperor’s prerogative. Now they must either take a clear humiliation, with possibly disastrous consequences to the prestige of the throne or go the whole way to national suicide.

A Thai explained that the Japanese were worried lest the emperor be brought to trial as a war criminal. A more reasonable explanation seemed to be that the Japanese government feared the Potsdam declaration on democracy might mean the forcible overthrow of the throne. At any rate the American reply is that the ultimate form of government in Japan.will be established on the basis of the freely-expressed will of the Japanese people which is a different matter since the Japanese will probably choose to retain the emperor.

A Chinese however doubted that Emperor Hirohito would personally survive defeat. He judged it probable that the present emperor would abdicate and leave the throne to the crown prince who, being still a boy, would not appreciate and suffer the indignities of surrender and who, if his coronation were suitably deferred, would not actually submit as emperor to the dictation of a foreign commander.

Some ambiguous echoes of this momentous debate have been allowed to reach the Japanese people. Commenting on the proclamation of the president of the board of information which only referred to ambiguous “utmost efforts” on the part of the government and called upon the people only to “overcome the present trial” and to protect ” the polity of the empire”, the Asahi today worried “How is His Majesty the Emperor? The concern of the 100 million people hangs on this question. when we turn our thoughts to it, we feel a pain in our breast. It is this pain that will enable us to bravely overcome the worst and last trial. So long as the loyal subjects have the ruler, the _____ to advance is clear and the glory of the empire will be maintained.”

And also, some gossip about the then-Crown Prince, the future Emperor Akihito:

There has also been a significant series of inspired stories on the crown prince. On the 11th the Times front paged an announcement that it had been decided to establish a separate household for the crown prince and that a grand steward, concurrently grand chamberlain, had been appointed for him. Yesterday the 12th the Times had a longer story, centered on the front-page…

A Japanese diplomat however explained to us that the stories were strictly routine and not a preparation for the emperor’s abdication. Every crown prince, upon completion or the primary grades in the company of other boys, takes up higher studies by himself under a faculty of tutors. This accounts for the establishment of a separate household at this time.

In Iwahig, Antonio de las Alas records the news that has filtered through:

This day we received official news that Japan had offered to surrender with only one one reservation — Emperor Hirohito be allowed to continue. We could understand this. To the Japanese, the Emperor is not only a political head, he is also a God, the head of the Japanese religion. Furthermore, without the Emperor, there would be revolution, chaos in Japan.

We also learned officially that the United States, Great Britain, Russia and China accepted the offer of Japan with the clarification that Emperor Hirohito would have to govern under the orders of the United Nations’ Commander-in-Chief in Japan who will be an American.

August 14, 1945: Japanese accept unconditional surrender; Gen. MacArthur is appointed to head the occupation forces in Japan.

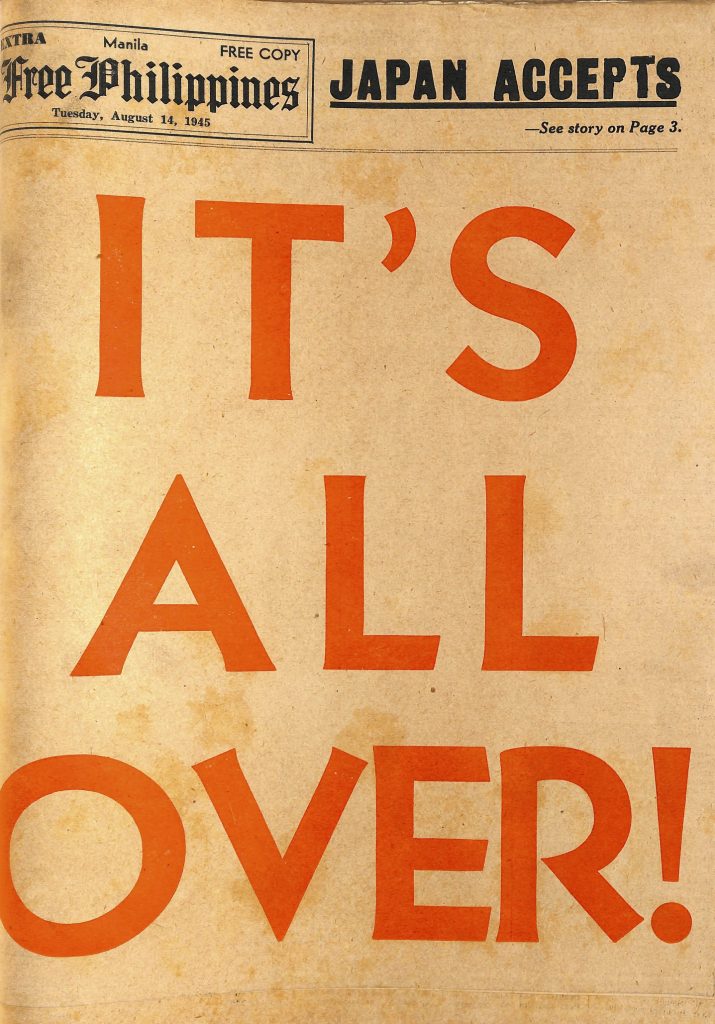

And the extra edition eagerly awaited:

In Iwahig, in detention, Antonio de las Alas records exciting news:

FLASH!

WAR IS OVER!

Japan has accepted all the terms of surrender. Now the announcement is official.

Rejoicing all around. Everybody believes that we will soon be out. I was asking myself however, “What will be the next step with reference to us?” I asked myself this question since in recent years, especially during the last months, we have experienced so many disappointments that I always fear that another one is forthcoming.

In a second entry for the day, Antonio de las Alas added,

The Lieutenant came and told us that Admiral Nimitz is now conferring with the Japanese officials, probably on the terms of the Armistice. Some consider this a blow to MacArthur as he must have been expecting that he would be the one to sign the Armistice agreement and to receive the surrender of Japan.

The Lieutenant also told us that the Domei had been communicating in code with all radio stations controlled by the Japanese. We suspected that instructions concerning the war are being transmitted.

But in Tokyo, no news, only rumors, as Leon Ma. Guerrero recorded:

Tokyo was still silent on peace today and the rumor spread that an atomic bomb would be dropped on the capital if the American terms were not accepted by the 18th. But in all probability they will be accepted. It has been announced that the emperor will have an important message for the Japanese nation tomorrow morning. Even the Japanese in the hotel are now talking in excited whispers. Some suspect the truth; others believe the emperor will call upon all his loyal subjects to fight to the end; but most do not know what will come tomorrow. They wait with a silent submissiveness to do what they are told.

August 15, 1945: Japan Agrees to Surrender; Attempted Military Coup in Tokyo

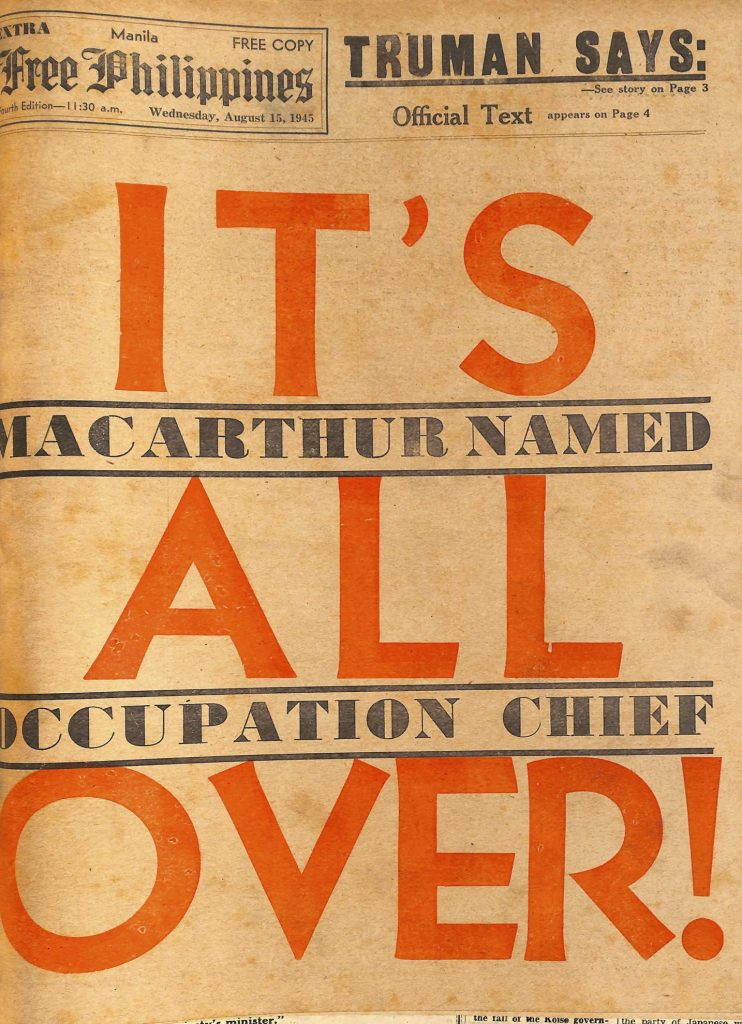

And the 4th edition of the paper, particularly thrilling news for Filipinos:

For Japan, it would be the “Jewel Voice Broadcast” that would leave its indelible stamp on history:

(Above: The Gyokuon-hōsō or Jewel Voice Broadcast, of Emperor Shōwa, August 15, 1945)

Tokyo, Leon Ma. Guerrero listened to the historic broadcast of Emperor Hirohito and the immediate reactions of his subjects. A prologue, of sorts, as people heard a broadcast would be made and gathered around to hear it:

The war is over. At noon today the emperor personally broadcast his rescript proclaiming peace. The Times, which ran the complete text under a modest three-column head (His Majesty Issues Rescript to Restore Peace), was held until the broadcast was over and we did not get the English translation until late in the afternoon. …

It was difficult to tell today from any other day. There were more people than usual in the tea lounge but they talked of every-day things. The maids and the waitresses shuffled along the corridors with unhurried pace. Their faces were drained of emotion and they averted their eyes. Somehow one did not feel like intruding into their thoughts.

The hotel radio was kept in the bird-room, behind the cashier’s little enclosure. Originally it had been a powerful American set encased in an ornate wooden cabinet. But sometime during the war the machine had been torn out, possibly to prevent anyone from listening to the forbidden shortwave, and now it rested, a tangle of tubes and wires, on a coffee table next to the disembowelled cabinet. It was now a very bad radio, connected by a complicated and clumsy network to a cheap round amplifier, but it was the only one in the hotel.

Around it now, in the neat little room with its three birdcages overlooking the ornamental fish-pond, the Japanese began to gather. The Germans, the Italians, the Thai, the Chinese, and the Burmans, kept to themselves in whispering groups along the corridor outside or, just beyond hearing distance, in the tea lounge and the lobby. But the Japanese crowded around the radio. The local chief of the military police was one of the first to arrive, a crop-haired, gold-toothed man with a Hitler moustache. He was not smiling now. The representative of the foreign office came next, tall, thin, and rabbit-faced. He did not speak to the kempei, although they were standing side by side at the foot of the stairs leading to the hotel theater.

Then, as noon drew near, the maids and the boy-sans and the waitresses, the cashier and her assistant, the reception clerks and the cooks, the embassy stenographers and interpreters, took their places around the wretched little mess of dull glass and steel which would soon enshrine the voice of the God-Emperor. In their stiff shy way they crowded upon each other; almost it seemed that they were huddling together for comfort, for some measure of assurance in the face of destiny.

There was complete silence as the clocks ticked toward noon. It was stifling. The windows had been closed to keep out the noise of the children playing by the pond outside. The waiting was oppressive and we watched the plump gleaming fish sliding smoothly against one another as they crowded obediently around the large black rock where the children stood, feeding them crumbs.

A Japanese woman married to an Italian tiptoed in. She was leading her two-year-old son by the hand. He was inclined to be difficult and to amuse him she showed him how to play with the song-birds caged beside the window. There was a smell elevator attached to the side of the cage and one placed a tender leaf or a pinch of golden seed in the straw basket at the end of the string.

Then the birds would hop to a tiny platform, thrust their delicate beaks through the bamboo bars, and pull the basket up.

A nine-year-old Italian boy sidled in, a tough bright youngster. A few days ago his mother had quarreled with the wife of another Italian, a New Yorker. The New Yorker’s husband had promptly smashed the other husband in the face, sending him to bed for a week. I wondered vaguely how the boy felt about his father now.