(Revised, April 8, 2017) The Philippine Diary Project includes the diaries of a father and his son: Victor Buencamino, and Felipe Buencamino III. At the outbreak of the war, Victor Buencamino was head of the National Rice and Corn Corporation, precursor of today’s National Food Authority. His published diary covers the period from the arrival of the Japanese in Manila, and the first half of the Japanese Occupation.His diary provides an in-depth look into the dilemma facing government officials who stuck to their posts despite the withdrawal of the Commonwealth Government and the occupation of the Philippines by the Japanese. At certain points, particularly from January-April, 1942, he gets intermittent news about his son (who was, on the other hand, participating in clandestine military intelligence missions, even in Manila).

Particularly gripping are his entries for April, 1942, when on one hand, he is wrestling with increasing Japanese interference and intimidation –including his being summoned to the dreaded Fort Santiago, where other members of his staff had already been summoned and in at least once instance, tortured– and on the other, frantic for news about his son, particularly after the Fall of Bataan, when on the same day he received condolence messages and news his son was alive. Then, he recounted the grief of parents and his own search of the concentration camps.

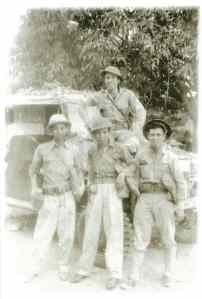

As for Victor Buencamino’s son, Lt. Felipe Buencamino III, known to his friends as Philip, was a young journalist who became a junior officer in Bataan, assigned to General Simeon de Jesus headed military intelligence. He kept a diary from the time of the retreat of USAFFE forces from the outskirts of Manila to Bataan, and conditions there as well as in Corregidor, which he periodically visited, looming defeat, the eve of surrender, and then the Death March and then wrote a kind of diary-memoir of the ordeal of his fellow prisoners in the Capas Concentration Camp, as well as his classmates. At times, his diary intersects with other diaries, such as the diary of Gen. Basilio J. Valdes, since Philip accompanied the General during one of his visits to the frontlines in Bataan. He resumed his diary, briefly, in September to December, 1944.

His Bataan diary prominently features two close friends: the writer and future diplomat Leon Ma. Guerrero (who would later keep a Tokyo diary covering the last months of World War II in Japan and the first months of the Allied Occupation), and Fred Ruiz Castro, future Judge Advocate General of the Armed Forces of the Philippines and who ended his career as Chief Justice of the Philippines.

After the Death March and imprisonment in Camp O’Donnell, Lt. Buencamino would go home and convalesce. His diary resumed in September, 1944, and covers the start of Allied air raids on Manila, and the preparations of Japanese forces for what would be the Battle for Manila.

During Liberation, he became did a stint in the newspaper published by the Allied forces and then joined friends in setting an early post-Liberation paper. He also became a broadcaster.

He left journalism to begin a career in the new Philippine foreign service.

On April 28, 1949, Felipe Buencamino III, together with his mother-in-law, Aurora A. Quezon, sister-in-law, Maria Aurora Quezon, and Ponciano Bernardo (mayor of Quezon City) and others, were killed in an ambush perpetrated by the Hukbalahap

Leon Ma. Guerrero, in writing about Mrs. Quezon and the ambush in which she was killed, in 1951, also wrote about his friend, Philip:

In Bataan I shared the same tent with Philip Buencamino, who was later to marry Nini Quezon. He was the aide of General de Jesus, the chief of military intelligence, to which I had been assigned. I remember distinctly that one of the first things Philip and I ever did was to ride out in the general’s command car along the east coast out of pure curiosity. The enemy’s January offensive was turning the USAFFE flank and all along the highway we met retreating units. Then there was nothing: only the open road, the dry and brittle stubble of the abandoned fields, and in the distance the smoke of a burning town. We turned back hurriedly; we had gone too far. I am afraid we never got any closer to the front lines. Our duties were behind the lines. We were quite close during the entire campaign until I was evacuated to the Corregidor hospital, and I developed a sincere admiration for Philip. He was a passionate nationalist who could not stomach racial discrimination, and I remember him best in a violent quarrel with an American non-commissioned officer whom he considered insolent toward his Filipino superiors.

The late Fr. James Reuter, SJ, wrote about it in 2005:

On April 28, 1949 – 56 years ago, Doña Aurora Aragon Quezon was on her way to Baler. With her eldest daughter, Maria Aurora, whom everyone called “Baby”. And with her son-in-law, Philip Buencamino, who was married to her younger daughter, Zeneida, whom everyone called “Nini”. Nini was at home with their first baby, Felipe IV, whom everyone called “Boom”. And she was pregnant with their second baby “Noni”.

On a rough mountain road, in Bongabong, Nueva Ecija, they were ambushed by gunmen hiding behind the trees on the mountainside. The cars were riddled with bullets. All three of them were killed. Along with several others, among them Mayor Ponciano Bernardo of Quezon City.

Adiong, the Quezon family driver, was spared. Running to the first car, Adiong found Philip lying on the front seat, his side dripping blood. Philip smiled at Adiong and said: “Malakas pa ako. Tingnan mo” — “I am still strong. Look!” And dipping his finger in his own blood, Philip wrote on the backrest of the front seat: “Hope in God”.

When they placed him in another vehicle for Cabanatuan, his bloody hands were fingering his rosary, and his lips were moving in prayer. This was consistent with his whole life. His rosary was always in his pocket. And on his 29th birthday, exactly one month before, on March 28, 1949, at dinner in his father’s home, he said to Raul Manglapus: “Raul, the Blessed Virgin has appeared at Lipa, and has a message for all of us. What are we going to do, to welcome her, and to spread her message?”

He was echoing the thoughts of Doña Aurora, who wanted a national period of prayer to welcome the Virgin and to spread her message of Peace. Years later, the Concerned Women of the Philippines established the Doña Aurora Aragon Quezon Peace Awards, choosing the name in honor of this good, quiet, peaceful woman.

The blood stained rosary was brought to Nini, after Philip’s death. Many years later, she wrote down the thoughts that came to her when they gave her the bloody beads:

“We had joined my mother in Baguio for Holy Week, 1949. As we drove down the zigzag, after attending all the Holy Week services, Phil turned to me and said, ‘Nini, if we were to have an accident now, wouldn’t it be the perfect time for us to go?’ I said to him, ‘You may be ready, Phil, but I still have a child to give life to, so I can’t go just yet.’ And not long after this, his life was taken, and mine was spared.”

Her life was spared, but she felt the agony of those three deaths more intensely than anyone else. In that ambush she lost her husband, her mother, and her only sister. The gunmen riddled their bodies with bullets, on that rough mountain road. But miles away, with her one year old baby in her arms, and another baby in her womb, the gunmen left her with a broken heart. The ones she loved went home to God. But she had to carry on.

Another friend of Philip’s, Teodoro M. Locsin, whose wartime diary is also featured in the Philippine Diary Project, wrote about the murder of his friend, in the Philippines Free Press: see One Must Die, May 7, 1949:

I knew Philip slightly before the war. We were together when the Americans entered Manila in February, 1945. We were given a job by Frederic S. Marquardt, chief of the Office of War Information, Southwest Pacific Area, and formerly associate editor of the Free Press. Afterward, Philip would say that he owed his first postwar job to me: I had introduced him to Marquardt.

Philip and I helped put out the first issues of the Free Philippines. We worked together and wrote our stories while shells were going overhead. Philip was never happier; he was in his element. He was at last a newspaperman. He had done some newspaper work before the war, but this was big time. We were covering a city at war. Afterward, we resigned from the OWI, or were fired. Anyway, we went out together.

Meanwhile, we had, with Jose Diokno, the son of Senator Diokno, put out a new paper, the Philippines Press. Diokno was at the desk and more or less kept the paper from going to pieces as it threatened to do every day. I thundered and shrilled; that is, I wrote the editorials. Philip was the objective reporter, the impartial journalist, who gave the paper many a scoop. That was Philip’s particular pride: to give every man, even the devil, his due. While I jumped on a man, Philip would patiently listen to his side…

…As for Philip, he was eager to work, willing to listen, and devoted to the ideals of his craft. He was always smiling—perhaps because he was quite young. He had no enemy in the world—he thought.

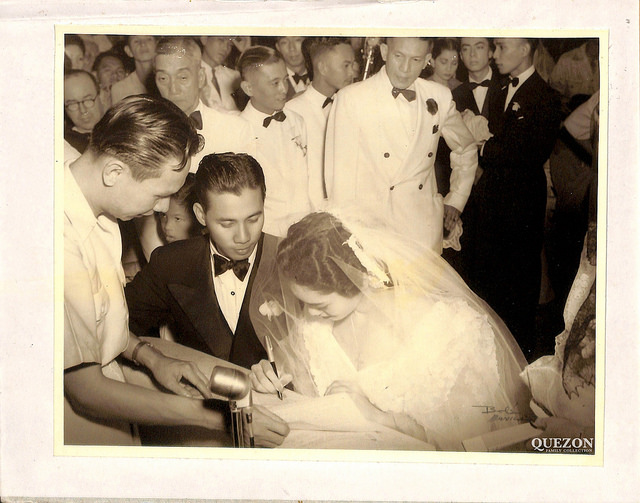

After the paper closed up, Philip went to the Manila Post, which suffered a similar fate. Philip went on the radio, as a news commentator. He had a good radio voice; he spoke clearly, forcefully, well. He married the daughter of the late President Manuel L. Quezon, later joined the foreign service. But he never stopped wanting to be again a newspaperman. He would have dropped his work in the government at any time had there been an opening in the press for him.

Philip never spoke ill of Taruc. He saw the movement, of which Taruc was the head, as something he must cover, if given the assignment, and nothing more. Belonging to the landlord class though he did, he did not rave and rant against the Huks.

He had all the advantages, and he had, within the framework of the existing social order, what is called a great future. He was married to a fine girl and all the newspapermen were his friends. They kidded him; they called him Philip Buencamino the Tired, but they all liked him. He wanted so much to be everybody’s friend. he got along with everyone—including myself and Arsenio H. Lacson.

When he returned from Europe to which he had been sent in the foreign service of the Philippines, he was happy, he said, to be home again, and he still wanted to be a newspaperman. His wife was expecting a second child and life was wonderful. Now he is dead, murdered, shot down in cold blood by Taruc’s men.

He was, in the Communist view and in Communist terminology, a representative of feudal landlordism, a bourgeois reactionary, etc. I remember him as a decent young man who tried to be and was a good newspaperman, who used to walk home with me in the afternoon in the early days of Liberation, munching roasted corn and hating no one at all in the world.

A few days earlier, the other friend mentioned by Locsin —Arsenio H. Lacson on May 3, 1949— had also paid tribute to his friend, Philip:

Until now, I can’t quite get over Philip’s tragic death. He was first of all, a very close friend of mine. I saw him married, and was one of the best men at his wedding. I also saw him buried, and it is not a pleasant thing to remember.

Philip was such a nice, clean boy, friendly, warm-hearted and generous, so full of life, and laughter, that I learned to love him. Of course he had his faults, but you take your friends as they are, not as you want them to be. And Philip, for all his faults, was quite a man. In all the years that we kept close together, I never knew him to deliberately do a mean thing.

Because he was by nature easy-going and amiable, he exasperated me at time by failing to take things more seriously and using his considerable talents to point out the many evils with which our government is cursed. Actually, he was not wholly indifferent to them. He could on occasions become quite angry over certain injustices, but he had no capacity for sustained indignation, and it was not in him, to fret and worry over the distraceful and scandalous way this country is being run. Life to him was one swell adventure, to be lived and savored to the full, with very little time left for crusades. The world cannot be changed or saved in a day.

And because he was Philip, he would gaily twit me about being afflicted with a messianic itch. Relax, he would say. Take it easy. Things are not as bad as they look. In time, everything would be alright. Perhaps, he had the right answer. I wouldn’t know. But I shudder to think what would happen if all of us adopted a carely and carefree attitude and paraphrasing archie, Don Marquis’ cockroach reporter, say:

no trick nor kick of fate

can raise me from a yell,

serene I sit and wait

for the Philippines to go to hell.The last time I saw Philip was two days before his death. Linking his arm to mine with a gay laugh, he dragged me to Astoria for a cup of coffee. We joined a boisterous group of newsmen who flung good-natured jibes at Philip when he announced that he was quitting the government foreign service to settle down to a life of a country farmer. Somebody brought up the subject of a certain Malacañan reporter who always made it a point to take a malicious crack at Philip and his influential family connections, and Philip agreed the guy was nasty. It was typical of Philip, however, that when I curtly suggested that he punch the offensive reporter on the nose, he smilingly shook his head saying: “How can I? Every time I get sore, the fellow embraces me and tells me with that silly laugh of his ‘Sport lang, Chief.’ I can’t get mad at him.”

That was Philip. He couldn’t get mad at anyone for long. He liked everybody, even those who, regarding him with envious eyes as a darling Child of Fortune, spoke harshly of him. He was essentially a nice, friendly guy. It was not in him to harm anybody, including those who tried to harm him.

And now he is dead, along with that fine and noble lady who was his mother-in-law, and that vivid, great-hearted, spirited girl who was so much like her great and illustrious father, foully murdered by hunted and persecuted men turned into wild, insensate beasts by grave injustices –men who, in laying ambush for Mr. Quirino and other government officials, brutally and mercilessly struck down innocent victims instead.

Philip Buencamino III had so much to live for: a charming, gracious wife who adored him, a chubby little son who will one day grow up into sturdy manhood with only a dim memory of his father, and another child on the way whom Philip now will never see. Handsome and talented, Philip had his whole future before him. His was a life so full of brilliant promise, and it is a great tragedy that it should have ended soon. He had been a top reporter before he entered the foreign service. With his charm and affability, his personal gifts and family prestige, there was no height he could not have scaled as a diplomat. The pity of it, the futile pitiful waste of it! A nice, clean, promising youngster sacrificed to the warring passions of men who have turned Central Luzon into a charnel house.

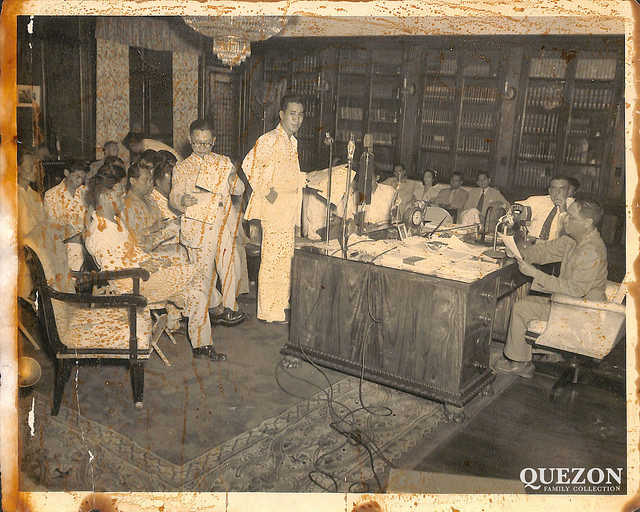

On a final note, you can listen to Felipe Buencamino III: He was the emcee for the Malacañan Press Corps, in the first radio press conference of President Roxas broadcast from Malacañan Palace in 1947.