GETTING SETTLED AT JANIUAY

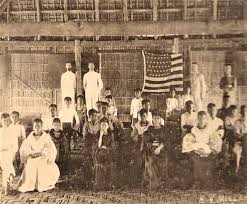

Before I reached Janiuay, I had been told that there was one American, an enlisted man in the United States Army, stationed here. On being dropped at the corner of the plaza the other day, I immediately went in search of this man and luckily soon found him. Otherwise, my means of communication with the denizens of the locality would have been of the most primitive sort indeed. Lazy, shiftless, trifling, and no-account as this enlisted man is, he serves me well indeed. He is quartered in the magnificent big convento, or parish priest’s residence, with a detachment of about a dozen Philippine Scouts. Since there is plenty of room and to spare in the building, I invited myself to take quarters therein and proceeded to settle down. But McC—— arranged for my meals and acted as interpreter; for although his knowledge of Spanish and the native dialect is probably very scanty and his expression of them lame and halting, still he has an eloquence of gesture, which seems to make up for all his other deficiencies.

The town Janiuay is beautifully laid out, but in a woeful state of repair. The plaza hes wonderful possibilities, but Looks more like a neglected blue-grass common than anything else. The high-road, from Cabatuan rolls in from a southerly direction over a series of hills so steep the that the distance measured on the level is well-nigh doubled; another road leads eastward down the valley of the Suague to Pototan; another northward (and upward) to Lambunao; and a carabao trail goes off to the westward up the Suague to the mountains. With the exception of a few structures, the whole town is a series of bamboo-nipa shacks faced, flanked, and rear-guarded by groves of coco palms; while on looking out from the vantage point of the convento across the place toward the mountains, one gets a splendid view reminding him strongly of the verdure-clad spurs around Honolulu.

The building in which I have taken up my residence is said to be the most beautiful of its kind in the entire province. Although it is properly the parish priest’s residence, and although there is a parish priest in the town, the military have not yet vacated it, having “occupied” it for purposes of quartering troops a couple of years ago. It is a marvel of construction, being built almost altogether, inside and-out, of a native hardwood called narra, excepting where stone is used in some of the supporting walls. Several of the massive doors are constructed each out of a single plank thirty or more inches wide; while plain boards two feet wide in the partitions are not uncommon. The lumber in the building would be worth a handsome fortune anywhere in the States. The convento and the parish church are really two structures in one, built so that there is a large rectangular court in the rear bounded on the west by the nave of the church; on the north by the main portion of the convento containing the reception and guest rooms; and on the east by a wing of the convento containing the kitchen, dining room and priest’s bed-room. All along the outer edge of the convento there is a corridor some four feet wide, the same being shut off from the rooms within by board partitions reaching clear to the ceiling and from the outer world by elegant shell windows, which slide horizontally upon the hardwood sills. Thus the essential portions of the building’s interior space are afforded a double protection against the violent storms that sweep the country from time to-time; while in fair weather the shell windows are pushed back for the sake of ventilation and also to enable the observer to get a wide-angle view of all that may be going on up and down and around the plaza and main residential portion of the village (for the church and convento are situated upon rising ground immediately to the south of the plaza).

I have never seen or heard of the like anywhere else in the world for dogs and dog-fights. They go far toward relieving the monotony of life in an out-of-the-way place like this. The streets literally swarm with nondescript curs of the most villainous end worthless sort, which are neither fed anything by their owners (if they have any owners) nor ever mercifully put out of the way. They prey upon everything, including one another, and are so ill-tempered that never an hour, or a half hour, of the day or the night goes by without a battle royal. Even as I write, I can hear the ki-yi of Some poor cur who is no doubt being pounced upon by all the other beasts in the town.

There is a strange little animal staying around the convento, although it is not new to me, as I heard its cry in

Manila a number of times. I think it is a lizard of some sort, although I haven’t seen it as yet. The most striking thing about it is its cry, which consists of two series of sounds —the first being a sort of warning that it is going to, while the second is the major strain, so to speak. The former consists of two or three series of guttural, muffled, ratchet-like uvular syllables, which remind one of the sounds given off by an old-fashioned wooden clock when the winding key is turned half way round at a time. The major strain is a repetition (usually about seven times) of a couplet of syllables sounding so much like ” geck” and “oh-h-h” that the animal is commonly called the gecko. By the time it reaches the sixth or seventh “geck-oh,” its bellows is often depleted that one hears only the syllable “oh-h-h,” and very faintly at that.

In the afternoon of my first day here, McC—— and I went to call upon the native presidente, or head-man, of the village, to whom I bore a letter of introduction from the division superintendent of schools. The presidente was not at home, but soon after we had returned to the convento, he came up. I was introduced and he at once assumed the entire burden of the conversation and delivered himself of a prolonged harangue accompanied by gestures which marked him as a spell-binder to the manner born. Every word of it was babel to me, but McC—- — told me that what the presidente said was in effect that he had not “gone out” when the Americans came but had stayed right in the pueblo and been a firm friend to the Americans all the time. The only question of business that came up was when the presidente asked whether or not the town was to pay my salary. Upon being assured that the Insular Government would take care of that item, he seemed satisfied (although apparently to my mind somewhat suspicious) and the interview ended.

Yesterday evening, McC—– and I strolled out a mile to the east of the village to see the cemetery. As is usually the case during daylight hours, an interment was going on. The people of the parish are dying like flies of under-nourishment and mountain fever. Scarcely an hour passes by without one’s seeing a body borne past the convento on the way to its final resting place. When a poor person dies, his body is usually wrapped up in some cheap material like matting made from the buri palm leaf, placed upon a simple bamboo litter, and borne away upon the shoulders of relatives or friends to the church, where only the very simplest of rites are administered. If the deceased was a well-to-do person, his body is carried or hauled on a sort of triumphal car to the church, where a rather elaborate ceremony is gone through with, which involves a great deal of ringing of the discordant bells in the church tower. In such cases the funeral procession going from the home to the church and from the church to the cemetery is invariably accompanied by a band of native musicians, who play the most sweetly weirdly mournful minor music. On the return from the cemetery, something more sprightly is the rule. I will not vouch for the truth of the statement that it is not uncommon for “Hot Time” to be played on such occasions. I have not heard it as yet.

The street Leading from the plaza to the cemetery is appropriately named “Calle de Pasos Finales” (Street of the Last Journey). The cemetery is enclosed by an iron picket fence, every post of which is surmounted by a plaster representation of a death’s head, or a skeleton, or something equally frightful and gruesome.

The people of Janiuay seem to be of the most hospitable sort and are by no means lacking in a knowledge of what constitutes good form in both personal and official life. I had scarcely gotten settled in my quarters when a number of young people came up to call. First of these was Juan Munieza, brother to Estéban the parish priest. Poor Estéban is sick, apparently unto death, with amoebic dysentery. McC—– and I went to see him and to offer our services in case we might do anything for him. We round the windows and doors of the sick room tight shut and the curtains drawn about the bed, so that not a breath of fresh air could reach the sufferer. We suggested that arrangements be made for better ventilation, but the attendants demurred. From what we were able to gather, it seems that the people have a belief that in such cases extreme precautions must be taken in order to preclude the possibility of evil spirits coming into the patient’s presence. Later, we got the Army doctor up from Cabatuan, but I fear there is no help. Everybody, both American and Filipino, seems to be very fond of “Padre Esteban.”

Every Friday is market day at Janiuay, end yesterday I took advantage of the first opportunity for getting a casual

look at the workings of the institution. The market-place, which occupies the first three or four hundred feet of the plaza end of Calle de Pasos Finales, with its stalls, booths, and amusement features, brings to mind many things one sees on circus-day in some parts of the States.

All the men, women, and children from all over the surrounding country had come in to barter whatever they were able to carry, drag, or haul; and incidentally to gossip, drink a little tuba, make themselves sociable generally, and forget their woes; for Heaven knows, if there is a people in all the wide world burdened with real woes, that people must be the seemingly gentle, peace-loving, primitive peasants of this region.

One of the delicacies to be had at the market was a big black water-beetle that had been dried and then crisped by heating. I noticed our cook eating some of these beetles with great relish and a noise that sounded like the “crackling of thorns under a pot.” He offered me some, but I thanked him and declined.

A veryregrettable feature of the temporary military occupation of the convento is that the parish library hes been torn up and scattered about. Musty old tomes in Latin, French, Spanish, and other languages, that must have delighted the heart of many a Spanish friar in the days gone by, are now lying about in this corner or that or have gone to feed the fires of the kitchen mechanic. I have tried to recover from the ruins a full set of Linnaeus’ Botany. There waS once here a Spanish edition in eight volumes, but I have been able to find only six of them.

Another dog-fight is going on as 1 bring this day’s chronicle to a close.