Last night we were entertained at the home of G. W. Wright, a leading missionary. We were the guests of the Evangelical Union of Manila. After a social time, in which about 35 people participated, I was called upon to speak to the company. I had felt most decidedly that a message was required of me, which I endeavored to deliver — a word of encouragement and suggestion. Afterward, some simple refreshments concluded a most agreeable occasion. It did me good to be with them.

My discriminating wife declares that the sundaes of Manila are very good. Indeed, for months we have sometimes been favored with excellent ice-cream made from condensed cream. Milk from the “iron cow” is not bad.

This morning I addressed the high school on “International Peace”. The student body constituted 600 young people and, as usual, they manifested intense interest. The Filipino audiences are more emotional and applaud much more easily than do those of China. A curious indication of the national temperament was manifested when I happened to refer to the sufferings of women in times of war. About half the students looked very sober, but the rest of them giggled. At the conclusion of the lecture one of the audience remarked upon the different mental attitude of many Filipinos toward trouble from that of Americans. For instance, a young person will, with smiles, announce that he or she has just lost a parent by death. A teacher in one of the schools of Manila told me recently that when she was going over a lesson she spoke of how Ghazan Khan had some of his enemies thrown into a caldron, of boiling oil. Immediately the whole class laughed outright. She asked, “Why do you laugh ? Would you like to be thrown into boiling oil?” They responded, “No.” At the same time the thought of suffering amused them very much.

Our intercourse with the educators of Manila has deeply impressed me with the feeling that whilst many of them are not church people, or identified with the missionary movement, they are at the same time animated by the most sincere interest in the moral and even religious advancement of the students under their control. The true missionary spirit is in some respects discovered in many of these teachers, and they gladly welcome the aid of outside workers who appeal to the better emotions of the heart. Some of them have warmly thanked me for my public advocacy of the religion of Christ as the hope of humanity. They tell me that God, and trust in Him, are too little spoken of in the schools of the Philippines, as, unfortunately, is the case in those of the home-land. These men are no doubt correct.

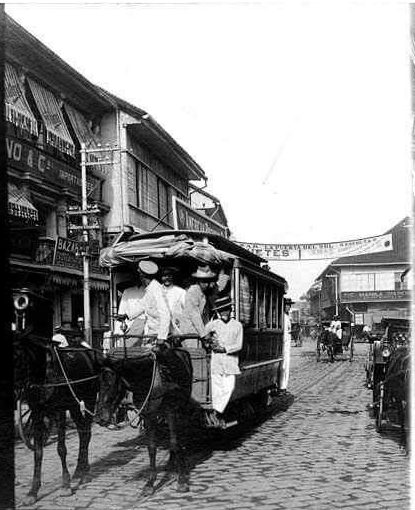

We go from place to place in “calessas,” which are peculiar to this country. They are much like old-fashioned chaises, and have broad seats between the two big wheels, whilst the drivers sit on little seats in front, close to the dashers. Sturdy ponies pull these vehicles. It is impossible to walk much in this climate. We see United States army and navy men patronizing these calessas very much. By the way, a few days ago a well-known man in Manila — whose name is nowhere mentioned in this diary — gave me an interesting description of how excitement reigned among the officers of the army and navy one year ago, when our country was so close to war with Mexico. My informant stated that some of these public servants were heard to say, “Now, we will have promotion,” or “Now we will have a chance to get better pay.” But when their hopes of advancement were destroyed by the peaceful attitude of the Washington Government, they were very bitter in denouncing President Wilson for refusing to embark our country into war with Mexico. Men in the army or navy often include most attractive personalities, but professionalism is naturally strong among them. Does this bode ill for the democracy of America?