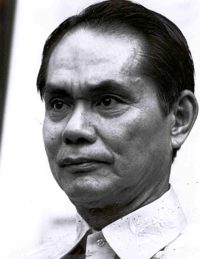

Moy Buhain, that good colonel, was again at the house at about 9:00 o’clock.

He informed me that according to some rumors, the President might yet want an election next year.

I said I would not rule that out. It is indeed possible that next year the President’s popularity might zoom up again and then he would prefer to be elected prime minister rather than continue with martial law. This one year of martial law may be a leeway for him to improve society as well as his chances of staying in power. So while the indications are that martial law may take a while, it might also happen that it may be cut short by the President himself if and when he feels secure enough in his position.

Moy was somewhat apprehensive about the duration of martial law. He was unhappy over the fact that there is no specific time mentioned for the transitory government.

At the session hall, a heated exchange had taken place between Vic Pimentel and Pacificador. These two delegates started challenging each other. Some delegates stood up to prevent them from getting to each other; but I heard some other voices saying, “Bayaan mo sila. Mabuti nga!”

Some delegates might just have wanted Pimentel and Pacificador to really come to blows with each other. For some reason, these two do not seem to be well liked in the Convention.

“Look at him strutting around like a peacock,” Sed Ordoñez, Pacificador’s former professor, whispered to me in contempt.

“Wrong, Sedfrey. A peacock is a beautiful bird.”

I had a brief chat with Munding Cea. He said that he cannot in conscience really lead the team of floor leaders. He said this is “lutong macao.” He said we were really instituting a dictatorship in the Constitution.

I am getting to respect Munding more and more for his decency and his respect for democratic processes.

I asked him how I could hest proceed with my plan of inserting my amendments. He said the best thing is not to speak now but to wait until the plenary session. I told him that I do not expect any discussion, much less do I entertain any thought of success. I simply want to have my thoughts inserted in the journal.

We talked about our colleagues who were in the army stockades. He said that not one of the delegates really deserves to be in prison.

The most ideological of them, I suggested, Boni Gillego, who alone among the delegates openly claims he is a Marxist, is really a social democrat. And he is patriotic, I said, and is concerned with fighting injustice, particularly the great and distressing gap in access to goods and services among our people. He mouths some Marxist terms but wouldn’t harm any one.

Munding nodded his head in agreement. “That happens to be his belief,” he said. “But he is not a violent man.”

I also chatted with Gary Teves and Aying Yñiguez. Gary said that Dr. Aruego, like me, is also doing a lot of writing now. He said it would be good for me to talk to Aruego about how the 1935 Constitutional Convention finally framed the Constitution.

Gary complained about the way the form of government has been distorted by the Steering Council. We had fought and won on the matter of changing the form of government to a parliamentary one but now, the government in the new draft is called a parliamentary one but in essence it is no longer parliamentary. It is really a very strong presidential government, with all the powers vested in the prime minister. The prime minister is now much stronger than the parliament.

“Gary, this is really a prime ministerial government,” I commented.

We noticed that Cefi Padua, Bobbit Sanchez and Joe Feria all stood up to question this on the floor. Tony de Guzman was answering all the questions almost mechanically and with great self-assurance. He was transparently showing his belief that the queries were really of no consequence; they were simply rituals to undergo.

Our idea, Gary said, was precisely because of the complexities of government, there is a great need to spread the loci of decision-making to a much wider group of people.

“Now, we have decision-making concentrated in one man. It would have been much more honest if we just made a Constitution for the duration of the martial law. He should have all these powers under the transitory provision.”

“I agree that there is need for a strong executive to hold the country together and lead it to paths of social progress, Gary,” I responded, “but it is also a fundamental principle in a democracy that all great decisions must be shared decisions.”

Gary is right. It would have been somewhat more justifiable if all of these provisions were put under the article on transitory provision—meaning, effective only during the state of emergency.

Aying Yñiguez had batted strongly for a parliamentary form of government but now he was saying he cannot defend it. “I will approve it, I will sign it, but I cannot defend it,” he admitted. “In fact, this is theoretically indefensible,” he added.

“Aying, why should a respectable guy like you, who is close to Marcos, not go to him and tell him: ‘Here in the transitory provision, we give you all the powers that you need. The rest of the Constitution shall, however, be rational with the great principle of checks and balances institutionalized.'”

He replied that this cannot be done anymore because there is really a cordon sanitaire around the President. Not even his father, Congressman Yñiguez, could penetrate this ring to see the President.

I asked him how the Americans look at this. He said that the Americans now approve of this—until such time as Marcos should blunder. He added that the government is really now embarking on a policy that would suit the needs of Americans.

Aying affirmed that the military is as strong as ever. He sensed, however, there is now a division in the ranks of the military between the old and the young. The old composing the leadership in the military, of course, fully support President Marcos. But this cannot be said of young military officers. And the President is aware of this.