War comes to the Philippines — Filipino farmers become demoralized — Communication with Manila ends — Col. W. E. Brougher visited — Rumours — Capt. Wade Cothran — Brougher fears the future — We flee to Baguio —

Panic siezes the populace — City officials take to the hills — Our last free Christmas — We go to the Country Club — We spend our last night as free-men.

“This means war” — that was my reaction to the news of the bombing of Pearl Harbor, on December 7th, 1941, as it came to me over the radio, at home at Manaoag, Pangasinan Province, from London at four o’clock on the morning of the eighth, Philippine time. For weeks we Americans in the Orient had been worried over the prospect of war between Japan and the United States for we were living within the shadow of the Japanese Empire. To us in the Philippines war meant ruin for it was a foregone conclusion that Hirohito’s legions would lose no time in attempting to occupy our beautiful islands. The unexpected had happened — a surprise attack while negotiations were under way in Washington between Ambassador Kichisaburo Nomura and Envoy Saburo Kurusu and Secretary Hull. While we were convinced that nothing would come of the talks because of the divergence of views there was always hope that some agreement might be reached. It is inconceivable that the two envoys did not know of Japan’s plans, for not long after Kurusu started on his flight to Washington via Manila the plane carriers sailed from Japan (November 27th) on their mission of death and destruction to Hawaii’s great naval base. Local Japanese must also have known of the plan of attack, for when a Japanese carpenter named Tanaka left one of the mines in the Baguio district for Japan a month before and his tool box subsequently (sometime in December) was torn from its fastening to the wall of a shop, this notation was discovered in chalk on the back of the cabinet: ‘The Japanese will invade the Philippines on Dec. 8th.’

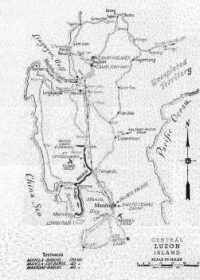

The news had an immediate effect on our Filipino cane planters and employees. The milling of cane and production of sugar became secondary to conjecture as to the future. After breakfast we left for Baguio — the Philippine summer capital and center of the Philippine gold mining industry forty miles away — to discuss sugar shipments with our agent. On the way up Kennon Road (the eastern entrance) we learned, over the auto radio, of

the bombing of Camp John Hay at Baguio and later in the day of the attack on Clark Field in Pampanga Province and Nichols Field near Manila.

Upon our return we found everybody in a state of panic. There had seemed to be no disposition to place much dependence upon the oft-repeated opinion that the Islands could be defended if attacked — and now the attack had come certainly to be followed by invasion. The army, represented in our section by the 17th Military District under Col. W. E. Brougher, commandeered our trucks for temporary use in the movement of troops and materials, requisitioned our picks and shovels and finally hauled off 4000 empty sugar sacks for use as sandbags. It is doubtful if the sacks were ever used for events moved too swiftly.

The local post office was taken over by our army on the 9th for military use and telegraph and mail services ceased. Mail did get through on the 13th and that marked the end of communication with Manila. Heavy fighting was reported on the 10th at Aparri on the north coast of Luzon and on the west coast in the Ilocos Provinces and the bombing of the Cavite navy yard without serious opposition from our own air force, shocked and surprised

us, although we continued to have hope in the fiction that Luzon, if not the entire Philippines, could be defended.

To halt or impede the southward drive of the enemy, bridges were blown up north of Bauang, a coastal town west of Baguio on the Lingayen Gulf. I called on CoL Brougher on the 11th to get first hand information of the situation and thereafter made daily visits until our evacuation became necessary. He was confident that the Japs could be stopped but he based his calculations on the ability of the inadequately-trained Filipino soldier to stand up under fire. On the several trips to Baguio in an effort to get in touch with Manila by mail, telephone or by telegraph (Baguio contacts Manila by radio while on the lowlands communication is by telegraph only) we noted thousands of Filipinos fleeing Baguio on the Kennon Road — the main outlet — as the mines shut down, and an almost equal number going to the mountains with a pitifully small supply of food. Poor people — they expected the trouble to end soon and hoped to make an early return to their homes. As for ourselves, on the assurances of Brougher that the situation was well in hand, we laid in an adequate food supply and felt sure that we could be independent of the outside for a long period. The natives who remained at home, fearing bombings, spent the nights under trees, in the cane fields and in the nearby foothills.

December marks the end of the rainy season in Luzon and the winds from the northeast assure the west coast of smooth seas and air conditions ideal for airplanes. Wise Japs, those! But December is a relatively cool month, the ”polar front” of the meteorologist being evident in the Philippines, and the natives suffered greatly from exposure. The nights were marked by total blackouts and we were constantly harangued over the radio by the

Bureau of Information of the Insular Government to stand firm, have faith in our army, go about our business as usual and, above all, admonished to keep calm. Everybody was doing it, the announcers said.

The natives were becoming increasingly nervous and almost hysterical. They did not know what to do; whether to stay at home or go into hiding in the nearby mountains and were it not for the cool-headedness of the officials of our little town and the activities of Mayor Ignacio Galaban, one of our cane planters, many of them might have marched off to join our forces in battling the japs in a futile attempt to stem their advance. One morning a group of Filipinos were sharpening their bolos in our shops (large, heavy knives resembling the Cuban machete) and upon being asked why this was being done one of the number said “We are making them sharp, sir, so we can kill the damn Japs.”

The army commandeered all liquid fuel and it became necessary for us to obtain a permit from Col. Brougher to acquire 500 gallons of gasoline most of which fell into the hands of the Japs later. Sales of sugar in Baguio increased in volume as soon as hostilities were declared, the Chinese merchants stocking up against future needs. As gasoline became scarce and the price rose to 50 cents a gallon and could only be obtained under permits from the military authorities, all sorts of hand-drawn conveyances, including wheel barrows, appeared at the door of our depot for sugar and trucks were loaded to twice normal capacity so great was the demand. On the 22nd the last load of sugar was dispatched to Baguio over the Naguilian Road which connects this mountain city with the Gulf on the west.

On the lowlands the roads were guarded by sentries at the approaches to every town and village. It became necessary to obtain travel passes from the 17th Distria headquarters. This only served to aggravate the gravity of the situation which, coupled with an absence of telegraph and rail communication with Manila and, of course, the non-existence of mail service tended to create panic and uncertainty.

Then came rumours. The Japs had landed. They hadn’t. Our troops were doing well. They were not — and so on. The most ridiculous story was that Chinese troops had arrived in Manila and were on their way north to defeat the Japanese! We were able to get our first authentic news of the military situation when Capt. Wade Cothran, a veteran of World War I who had been in business in Manila and who had joined MacArthur’s staff only a few days before, called upon us on the 19th. He did not paint an altogether gloomy picture of the general state of affairs but he was not too enthusiastic about prospects. He had with him some Japanese-made Philippine currency (Tokyo pesos) printed on cheap paper and bearing no serial numbers, which, as he put it, had been “landed by the bale at Vigan.” He thought that we were wise to remain at Manaoag and not evacuate to Manila which, of course, was agreeable to us. Cothran left early on the morning of Saturday, the 20th, to visit the war front 40 or 50 miles to the north along the coastal road, and in parting hoped to see us again soon, though he planned to return to Manila that afternoon. Much to our surprise he came to the house late that evening to spend the night and to get some food, for he had had none all day. He had an exciting tale to tell. Japanese bombers had forced his car off the road several times and he had been obliged to seek refuge in the bush. One or two planes had machine-gunned the road only a few yards ahead of him, and it was a miracle that he escaped unscathed.

We were losing ground in Northern Luzon, he said, and a landing in force in Lingayen Gulf was only a matter of time, no longer than the time required for a juncture to be effected between the Japanese, moving south, and the hordes of soldiers ready to disembark at the lower end of the Gulf. Now it was realized that a grim situation might face us within a very few days. (Capt. Cothran was later captured at the fall of Bataan, participated in the infamous “Death March” to the O’Donnell prison camp and lost his life in late 1944 when the ship, on which he and hundreds of other war prisoners were being transported to Japan, was bombed off the coast of Luzon. )

On the morning of the 21st we made another trip to Baguio for current food supplies. They could be obtained by means of permits issued by city officials, although this applied only to non-perishable foods. Perishables could be bought at will in the public market. Many prominent citizens had already left town, proceeding over the North Road further into the mountains. No supplies of any kind were coming in from Manila, gasoline stocks were getting low, some of the mines were operating on half time because thousands of laborers had already left for their lowland homes, and a general feeling of uncertainty and abandon had seized the populace. That the Japs were coming sooner or later seemed to be a foregone conclusion. On the way up we saw billows of black smoke, miles high and fully a mile wide, to the west, apparently on the coast. We surmised, quite correctly it transpired, what it was. Our troops had fired the oil tanks at Poro belonging to the several oil companies operating in the Islands. This put an end to diesel fuel supplies for the Baguio mines and hastened the day of their ultimate closure.

Between the 11th and the 22nd I continued my daily calls upon Col. Brougher. I found him to be an earnest and painstaking officer, who constantly kept in touch with the area under his charge and whose chief concern was the welfare of his native troops. Headquarters were on rising ground to the west of Manaoag. The buildings of the post were of thatched bamboo with matched lumber floors; comfortable and cool. At the Colonel’s quarters a sentry paced back and forth. On one of my visits I noted the guard on duty to be an employee who had been drafted into the service. Instead of challenging me, as is customary, this soldier dropped his gun to the ground, took off his hat and said, “Hello, Mr. Hind.” I wondered, then, if perhaps too much dependence was being placed upon the untrained lads who made up the Philippine Army, boys whose hearts were loyal but whose heads and hands could not efficiently serve in time of crisis.

On Monday morning, the 22nd, two weeks after the Pearl Harbor attack, I made my usual call on the Colonel. He was away from the post and I learned that he had been promoted to Brigadier-General that very day. Having left word that I had called, I had no sooner returned home before the General’s aide arrived to say that Brougher was at the post and awaited me. I returned at once. What I saw and heard were so unexpected that I could scarcely believe my eyes and ears. The General was spattered with mud from head to foot, and after greeting me he seated himself on a stool on the little porch of his quarters with a look of dejection on his face that is haunting to this day. He had just come from the Gulf where several times he had been obliged to take refuge in roadside culverts to avoid the effects of bombing by Japanese planes. He said that he had seen much disaffection among our native troops — men who, because of the lack of training could not stand up to enemy fire. “How can I fight,” said he, or words to that effect, “If I have men under me who have had but three or four days’ training?” It was plain that something was stirred deep down in this soldier’s heart.

Properly trained the Filipino is a good soldier and when led by American officers, whom they trust, there is no better in the Orient. Unlike the Japanese he is no fanatic but when fighting for his country, with his back to the wall as he was at Bataan, “fighting all day and falling back at night only to fight again on the morrow he is a tough soldier” — to quote General Brougher in the writer’s talk with him upon the General’s return from a Manchurian prison camp in San Francisco at war’s end.

We next discussed my plans. While Brougher felt that we would be safe at Manaoag for a while longer, he feared that we might be caught by cross-fire, as he put it, when the Japanese passed through this section of the country. That they would do so was a remote possibility, for the town is not on the direct road between Lingayen and Manila, the ultimate objective of the enemy sweeping to the south across the central Luzon plain. The events

of the next few days proved that the supposition was correct for Manaoag soon was occupied by the Japs, in common with all the towns in the archipelago. The General felt that it would be wise to go to Manila or to Baguio. He would not make a choice for us nor would he order us to leave. I could see, however, that he felt much relieved when I told him that we would proceed to Baguio.

There are scenes that all of us can recall out of our past that can never be forgotten. The parting from General Brougher was one. We both knew the thoughts of the other. How happy we would have been did we know that the immediate future held hopes of success to this gallant soldier. We had to content ourselves with hollow pleasantries. It was a sober situation that I faced as I turned my car homewards. There was to be no war — yet war had come; no invasion was expected — yet here it was; the Philippines could be defended — but could they? Nearly twenty-five years’ service in sugar in the Philippines was represented in my holdings at Manaoag — what were they worth and what would they be worth a month or a year from today?

Brougher fought to the end of the campaign finally surrendering at Bataan, was with the Death March, was later transferred to Formosa, then to Manchukuo and was released from prison in August, 1945.

Bags were hastily packed at home and many articles, technical books and such things, including General Brougher’s trunks, Oriental rugs, etc., which he had sent to us some days before for safekeeping, that would be necessary for a long stay in Baguio were set aside to follow by the sugar truck on its next trip to the mountain city. It was my intention to return on Wednesday (24th). As we were about to leave, the truck arrived. I sent for

the chauffeur to instruct him to make ready for an immediate return to Baguio. He was so frightened by what he had seen that day that I told him he could defer his departure until the next morning. He said that when he passed his home, which was on the main road, his family had fled, he knew not where, that Camp Three bridge on the Kennon Road was to be blown up that afternoon, that the Japs would soon be in Manaoag, etc. The truck

did not make the special trip. Demoralization, always contagious under circumstances such as these, completely gripped everyone including the truck driver.

To the accompaniment of heavy gunfire and bomb explosions at San Fabian (where, incidentally, General MacArthur was to land more than three years later) we left at about 2:00 P. M. in an automobile loaded to the gunwales with bags, bedding, food, odds and ends, including a radio, and four passengers — Mrs. Hind, my son John and his wife. As we came to the toll bridge just out of town the gatekeeper asked, “Are you going on a vacation?” It was just the sort of question a long-time resident of the Philippines might expect from an inquisitive but ingenuous native. What a “vacation” it proved to be! Four years would elapse before we could be home again, for my scheduled return on the Wednesday never was made. General Brougher and his men evacuated the town the next day.

As we passed along the Bued river canyon Filipinos were seen drilling holes in the banks at the cuts for future dynamiting to destruction and there were thirty or forty boxes of dynamite at Camp Three bridge supposedly for the blowing up of the structure as the truck chauffeur had reported. Dozens of truckloads of refugees were met, several buses loaded with Filipino volunteers in nondescript uniforms, all armed, going we knew not where and

many truckloads of dynamite which had been shipped out of the Baguio mining district.

The day before Christmas was one of excitement, rumour and prognostication. A few stores in Baguio were open. All plate-glass windows had been boarded up or were being protected against bomb concussion. All sales of goods were for cash, and the one drug store open for business was swamped with customers. The gold mines were destroying stored explosives and liquid fuel supplies, for the Japs were in control of the lowland approaches

to Baguio. It was reported that 100 transports were in the Gulf and another 40 were off the East Luzon coast south of Manila. Yet there was no word of the enemy approaching Baguio.

“Where are the Japs now? Are they on the Kennon or the Naguilian Road? Is Manila being attacked?” There was no communication with Manila except by radio, but that the “situation was well in hand” was the essence of all the broadcasts. However, a note of skepticism could be detected — doubt as to whether the Islands could be defended, not perhaps in so many words but by inference. MacArthur s daily communiques left much to be

desired, for they were not convincing. Hundreds of civilians had been given guns and ammunition, for what purpose it was not divulged, and the nights in our section of the residential area were made unpleasant by the Filipino guards firing their guns at imaginary targets! “Target practice, sir,” was the only answer one could get from them when queried as to the whys and wherefores of this miniature warfare but no information was volunteered as to what the targets were.

In view of the circumstances, the most important being the absence of police protection, for policemen and city officials had fled to the hills, we considered spending our nights at the Baguio Country Club. This was a refuge for many club members and guests and supplemented the haven offered by the facilities at the Brent School (a boarding school which, at the time, was idle because of the Christmas vacation) to many townspeople who

decided that group assembly was necessary for prompt and concerted action and for the execution of the will of the expected Japanese as to the disposition of non-belligerent whites. There was no doubt, now, that the enemy would soon be in the city.

Christmas Eve was a memorable one. It was the last spent under the family roof. Usually a cheerful and gay evening given to thoughts of good will, a Christmas tree, the exchange of gifts, complete freedom from worldly cares and dedicated to the thoughts of loved ones overseas, this initial celebration of the holiday season is pleasurably anticipated by all in the Philippines who hail from abroad. After a simple dinner, held early because of the blackout, which was in effect from Pearl Harbor day, we gathered around the radio to hear a Yuletide program. For obvious reasons there was none being broadcast in the Philippines. Terror and tragedy had struck our peaceful country. A station in Australia was dialed and from it we heard the familiar music and carols and the sentiments of Christmas. Yet Australia had been two years in the war! However, that country had not then been attacked by the enemy.

On Christmas Day we decided, in view of the uncertain local situation, to spend our nights at the club but to continue to have our meals at home. Accordingly, we moved over that afternoon. We slept, in common with 30 or 40 others, on mattresses placed on the floor of the newly completed sports pavilion. We had the most necessary clothes with us but little else. There were several air raid alarms while we were there and at each we would hurry

to the shelter that had been constructed under the floor of the sports building, immediately above which sandbags had been placed. It was amusing to have to rush to the semi-cavelike shelter and be uncomfortably crowded, like a lot of frightened sheep, until the “All clear” was sounded. At night a guard was formed of club employees to patrol the grounds under the watchful eyes of the male guests, who took turns at supervising the detail.

Our last meal at the club was dinner on Saturday, the 27th. Saturday night dinners followed by dances have always been a feature of the club’s activities. Of course, on this evening there was no festivity of this kind, not only because we were in no mood for it but the orchestra had fled, and club employees had been assigned to guard duty. We retired at about 10:00 o’clock. Everyone was nervous. Word had been received that the Japanese

were on their way up the Naguilian Road although there were no details as to the number of soldiers in the party, nor was there any intimation of what would become of us. Of course, there were rumours afloat that inasmuch as no resistance had been offered we would be unmolested, that business would go on as usual. We knew that the mines could not operate, because of the lack of oil and explosives, but “business as usual” allayed some apprehension. There was also talk of keeping us within certain residential zones.

All this proved to be idle gossip, for events in the early morning hours proved that Mr. Jap had very definite and preconceived plans for our disposition.