(Updated, February 1, 2019) February 3 to March 3 traditionally marks the period of commemoration for the Battle of Manila in 1945. The first diary to cover this period featured on The Philippine Diary Project was the first-hand account by Lydia C. Gutierrez, who was a young girl at the time. In fact her diary covers only ten days: from the start, to the end, of her family’s ordeal.

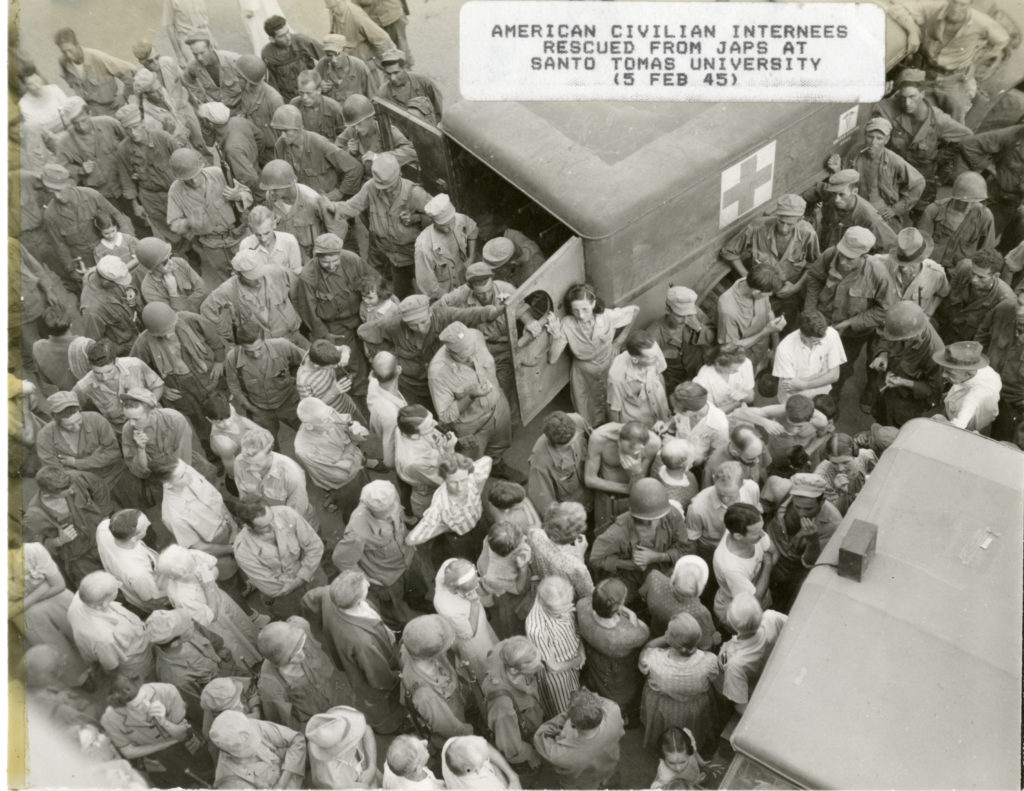

Civilians interned by the Japanese were in two locations: Natalie Crouter an American civilian, with her husband and children, had recently arrived in Old Bilibid Prison after years of being detained in Baguio; Albert A. Holland and Raymond Leyerly were civilian detainees in the University of Santo Tomas. Their diaries actually end just at the point when their imprisonment ended –while Holland would, afterwards, have a distinguished career, Leyerley died soon after being freed –of starvation.

American Prisoners of War included Ike Thomas, a staff sergeant in the Medical Department of Old Bilibid Prison, and his chief, Major Warren A. Wilson, who was overall-in-charge as the senior American medical officer in the prison. Both also end their diaries soon after their freedom was restored.

Outside Manila were the Spanish Dominican Fr. Juan Labrador, OP, who was in Pangasinan but would make his way to Manila; he would chronicle for posterity, the destruction and suffering of the city. Secretary of National Defense and Chief of Staff of the Philippine Army, General Basilio J. Valdes was with President Osmeña; his diary also peters off at the point he finally returned to Manila. In Tokyo, Leon Ma. Guerrero a junior diplomat in the staff of Ambassador Jorge B. Vargas, would get snatches of news about home.

The prelude to the Battle of Manila can be seen in the September-December, 1944 diary entries of Felipe Buencamino III, a veteran of Bataan who’d stopped writing in his diary in September, 1944, when the first American air raid of Manila since 1942 took place.

Here are the days with relevant entries in The Philippine Diary Project.

February 2, 1945

Albert A. Holland, UST (last entry in his diary):

There are reports – fairly reliable – of landings at Nasugbu Batangas 2 days ago and at Subic Bay 3 days ago – Nasugbu is to the South on the West Coast – Subic to the North on the West coast – the Subic landing aims at the capture of Olongapo, the naval repair base, the cutting of the communication of the Japanese forces resisting our advance over the mountains from the Zainbiales Coast, and our advance from Olongapo over the mountains to the East to cut the Japanese retreat into Bataan– The Musugbu landing will aim, of course, at the Cavite naval base, at cutting off a possible Japanese retreat to Teinate [Ternate] & Maic [Naic] & this evacuation to Bataan– And incidentally, after passing the Tagaytay ridge, will turn towards Manila.

Again these landings to the North & South of Manila Bay, the terrific bombings of Corregidor, Cavite Naval base, Fraile Island may be the prelude to an advance by task force into Manila Bay – the mines will have to be cleared and there are many wrecks in the harbor –

Gradually, the Japanese are being forced to decide what to do in the South – In a short time, any troops they have there will not be able to join the Northern forces –

Raymond Leyerley, UST:

Men are dying from starvation every day and day before yesterday, the Japs put two of our doctors in jail because they refused to change the death certificates from starvation to heart trouble, or some other ailment. Over 3/4 of the people in camp are starving. There are some who have a few cans of food left but even they no longer have enough to eat.

Ike Thomas, Old Bilibid:

Very heavy explosions in and around Manila all during the day. About 10:30 PM, a series of detonations lasting well over an hour, were heard to the southeast of the compound. The explosions varied in intensity from small ones to big ones, all mixed together. Artillery or destruction of installations? Reverberations from explosions were heard intermittently all during the night. Many of the personnel thinks it’s about over for us – that the Americans will take Manila within the next four days.

February 3, 1945

The same half-boring, half-scary life. Early in the afternoon Papa, Frank and Nong came home with 3 bayongful of money. (Papa had mortgaged the farm.) We knew that the Americans were near so we decided to spend the Japanese money quickly…

Baby and I spent the night in Frank and Josie’s at Georgia St. It was 9 p.m., but the skies were red and orange and bright like sunset because of the fires. We watched the fires from the porch and then went to bed. But I couldn’t sleep. I lay awake. I was very impatient and homesick. By midnight, we could hear faint machinegunning and shooting. But the sound was so far, far away. The night seemed so long.

Raymond Leyerley, UST:Entry 1:

Well, looks like the Japs are getting ready to evacuate Manila and suburbs. Lots of fires early this morning — they are destroying supplies and from the looks of things, burning up half of the country in doing it.

It was about 5:30 p.m. when we heard repeated and long bursts of heavy caliber machine gun fire along the North road. There was a deep rumble which sounded like airplanes but as there were no planes in sight, it boiled down to — tanks. Very soon the sound drew nearer and the machine gun fire hotter together with heavy tank guns 2.8″, I believe the caliber is. The boys were meeting with a little Jap resistance; but they soon overcame the weak and surprised opposition of the mighty Imperial Japanese Army and drove on to Bilibid and the Far Eastern University. There at the F.E.U., our boys had quite a fight. Some were killed and quite a number wounded. But they blasted the place all to hell, set fire to it and came on about their business.

At nine o’clock, it was very dark — the moon came about midnight; one big thirty ton tank drove into the front gate and another came through the Seminary road and just took the gate with it. The Japs were caught napping and a bunch of them ran into their quarters in the Education Building.

Natalie Crouter, Old Bilibid:

At dusk, we saw a silent line of Japanese in blue shirts creep from the gate to the front door. They went through the long hall, upstairs, and out on the roof—of all places—with machine gun and bullets, grenades and gasoline. This made us extremely nervous, to put it mildly.

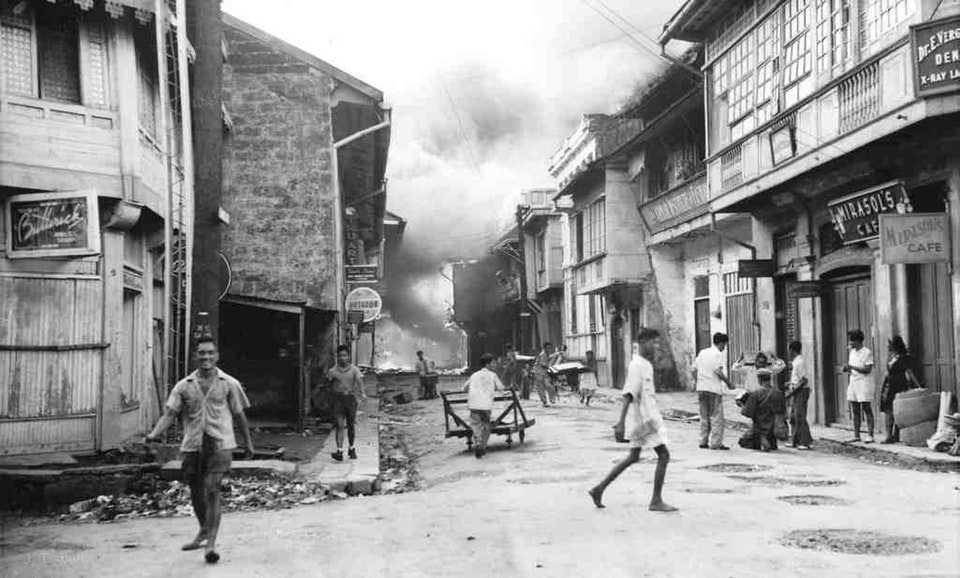

A flame thrower tore through the building next to the men’s barracks just outside the wall, and the building was a seething mass of flame immediately. It made me sick to see how quickly it happened and to wonder if any people might be inside. Fires began to rage in all directions. The sky was ablaze all night. The oil-gray pall has hung over us ever since, some of it a greasy brown color. At sunset, the sun was a copper disk in the sky, as it is during a forest-fire time at home.

Everyone went around talking about whether it was or wasn’t the American army. It wasn’t very long before we were sure. Some of the usual nervy, hardy camp members went up on the roof to see what was going on, and when the tank went by outside our walls, it stopped and they heard a Southern voice drawl, “Okay, Harvey, let’s turn around and go back down this street again.” Another pair of tanks was heard “God damning” each other in the dark. There was no mistake about this language—it was distinctly American soldiers! The Marines and Army were here! And they had caught the Japanese “with their pants down.” There couldn’t have been good communication or the Japanese would have had time to leave.

A fire broke out just behind us to the north, and the flame piled high and bamboo crackled and popped like pistols. I was so excited all night that I almost burst. I would doze off, waken with a jump at some enormous detonation. Win and Jo and little Freddie came down to our cement floor space for the night. I was up most of the night, going from one end of the building to the other to watch new fires that leapt into the sky. Jerry, who was tied to crutches (legs swollen with beriberi) and to his bed, scolded me—“You darn fool, go to bed. You’ll be dead tomorrow if you don’t stop running around.” He was right but I didn’t care and just answered, “I don’t care if I am. This is the biggest night of my life and I’m not going to miss it.”

Ike Thomas, Old Bilibid:

A very bright-red red letter day! Everything went along as usual, performance of routine duties, exchanging of rumors; evening chow, and then—six American planes flying extremely low and slow passed over the compound. “Tenko” (the Japanese word for roll call) as usual at 6:00 PM. At 6:30 PM, the sound of artillery in the distance. Then heavy machine gun fire. Then the machine guns seemed to come closer and closer and closer. Finally all hell broke loose in the city. Light artillery (or artillery on tanks), heavy machine guns, light machine guns, rifles, pistols –everything– sounded on the north-northeast and east of us. The Americans had come into Manila just before dark. It got dark but not for long. A huge fire was started in or close to the adjoining compound. This illuminated our compound. The buildings on the north and east of us caught fire and blazed up. The electricity went out about 10:30 PM to remain off. Guns and ammunitions dumps went off steadily until the close of Saturday Feb, 3rd, 1945.

At 5 p.m. advised by phone the President had arrived in his house. Went to see him. Found out we are leaving tomorrow.

Leon Ma. Guerrero, Tokyo:

With the Americans at the gates of Manila the official Imperial Rule Assistance Association called a “Victory in the Philippines” rally at the Hibiya public hall today. It was piercingly cold even in mid-afternoon and the steep backstairs were slippery with crusted ice. Backstage distinguished visitors were shown into a shabby clingy waiting-room and served the usual tea. Japanese officers and dignitaries arrived in succession, glum and blue with cold, and with a strange and awkward air, half-defiant and half-apologetic. Nobody talked about the war but it was obvious that for the Japanese the news was bad.

February 4, 1945

After Mass we went to market again. The girls dropped by from home and told us that Emy said that there was news from the Quemas that the Americans arrived last night in Caloocan and were coming towards Rizal Ave. That’s why we heard the machinegunning. It was so hard to believe! The majority of the people heard the good news and rushed to the market. The market was almost empty. There were just hard kernels of yellow corn, a few coconuts and kangkong and talinum…

The Japs look desperate. They were very, very strict with the people. People were slapped more often without knowing why.

Natalie Crouter, Old Bilibid:

About 10 A.M. we saw Carl go out the gate to join Major Wilson in receiving orders and release from Major Ebiko and Yamato, who at last satisfied his correct soul by turning us over with all the proper formality. About noon Carl came back and we were all called into the main corridor. We crowded about the small office space, then someone said, “Gangway.” We all pressed over to one side as the clank of hobnails and sound of heavy feet came from the stairs. The eight soldiers had received their orders to come down from the roof. This was the most dramatic and exciting moment of all. It pictured our release more vividly than anything could. They had been persuaded to withdraw so that our danger would be less. They were giving in that much and were leaving Bilibid. They filed through the narrow lane we left, they and we silent, their faces looking sunk and trapped. The corporal’s fat face was sullen and defeated. One short, beady-eyed, pleasant fellow looked at us with a timid friendly grin—a good sport to the end. With machine-gun bullets and grenades in their hands, they trooped out the door, joining the still jaunty Formosans at the gate. They all went out without a backward look, and the gate stood open behind them. We were alone—and turned toward Carl who read the Release. We cheered and then Carl took the hand-sewn Baguio American flag out of the drawer and held it up high. The crowd broke up and began to move away singing “The Star-Spangled Banner” and “God Bless America.” I went out the front door and around in our door at the side where June was trying to tell Jerry, who had his face in his hands, his head bowed. I put my arm around his shoulders, and the three of us sat there with tears running down our cheeks for quite a long while, not saying anything.

Ike Thomas, Old Bilibid:

The sound of tanks running, artillery firing, and small arms explosions continued unabated until about 2AM. The fires burned until everything was burned up. Great clouds of saffron colored smoke reflected the light. Finally everything quieted down, except in the distance where heavy artillery was in action. But the Yanks with tanks with steaks and cakes had not come into Bilibid at 7:30 AM. Last night everyone KNEW it was over. This morning there was much talk of last nights activity being just a commando raid. The Japanese guards, most of the morning, appeared to be on the point of leaving. At 11:00 AM, Major Wilson, the Senior Medical Officer, was called to the Japanese office, where he was informed that the Japanese “had been assigned another duty” and were going to release the prisoners of war, also the civilian internees in the upper compound. At 11:45 AM, the Japanese left. We had three meals; all of them heavy. A light plane circled over Bilibid many times during the day. About 6:00PM, a wooden shutter on one of the walls of Bilibid had a hole knocked in it with a rifle butt. The American guard (guards were posted to maintain order and to prevent anyone from trying to get out of or into the compound until American Forces came in) went up to see what was happening. Maybe it was Filipino, maybe Japanese.

But — it was AMERICANS. They had Bilibid completely surrounded and were trying to get in and see what was inside the walls. They said that they had expected Japs and were surprised to see Americans and we were happy to see them. The detail at that particular point, passed cigarettes through the bars, and kept saying, let us in. We’ve come to get you out. After seeing Major Wilson, the officer in charge of the American force surrounding Bilibid, Major Wendt, bivouacked his men and then came into the compound and told us that they had been averaging 20 miles a day on their advance, but that they had only made 15 miles today, that we would no doubt be taken over tomorrow. Later, men from his organization, the 37th Division, Ohio Regiment, came into the compound and visited with the ex- prisoners.

Warren A. Wilson, Old Bilibid:

The Japanese left the hospital area about 1:00 P.M., about 1:30 P.M. we locked the front gate with a chain and padlock and put up a red cross flag. Guards were place at sally port, outer compound gate, chapel (guard house) and west wall. I have kept the two compounds from fraternizing because they are not under military jurisdiction, however, I called on them this afternoon and we split stores left us for the Japanese – prorated their 465 to our 810 and gave them sugar, rice, tea and cigarettes to rate of 5 per person in each compound. Met the doctors including Dr. Marshall Welles formerly L.R.C.G.H…

Requested the outer compound to take down an American flag on their building as I felt this was premature.

Fr. Juan Labrador, OP:

The advance troops of the liberators entered Manila last night after thirty-seven long months since the remaining troops of the USAFFE retreated to Bataan. We cannot tell how many districts of Manila are already liberated. News dispatches are a little confused. All we are sure of is that the first place recaptured is the University of Santo Tomas with all its residents, priests and internees. We were told that the rest of the city had been turned into a battlefield, won not amidst psalms and cheers but amidst firings and shellings “…that this city and all its people might be protected…”

Got up at 5 a.m. Attended Mass at 6 a.m. Left at 9 a.m. on a B-24 with President Osmeña for Lingayen. Our plane was escorted by four pursuit planes. Arrived at Lingayen 11:30 a.m. Left at 3 p.m. for Hacienda Luisita. Spent the night.

February 5, 1945

Natalie Crouter, Old Bilibid:

I was awakened by feminine shrieks of delight and men’s cries of “Hooray!” Little Walter came rushing in calling to his mother, “Mummie, come, come! Do you want to see a real live Marine? They are here.” I was too worn down to go out and join the crowd, so I just rested there letting the tears run down and listening to the American boys’ voices—Southern, Western, Eastern accents—with bursts of laughter from our internees—laughter free and joyous with a note in it not heard in three years. I drifted into peaceful oblivion, wakening later amid mosquitoes and perspiration to listen to the rat-a-tat-tats, booms, clatter of shrapnel, explosions of ammunition dumps, seeing scarlet glare in every direction. There is battle all around us right up to the walls; two great armies locked in death grip. Today we watched flames leap and roar over at the Far Eastern University building just two blocks away. It is the Japanese Intelligence and Military Police Headquarters. The building was peppered with bullet holes Sunday morning, and a dead soldier is slumped out half across the window sill of an open window.

Ike Thomas, Old Bilibid:

At 9:00 PM Bilibid was reported surrounded by fire on three sides and we were ordered to evacuate to the Ang Tibay shoe factory on the outskirts of Manila, where 7th Division Headquarters were located. Members of the 148th Infantry assisted in the evacuation by carrying litter patients, helping the weak to trucks, and seeing that Bilibid was cleared. The litter patients were evacuated in ambulances and jeeps. At 11:35 PM Bilibid was cleared of all personnel, staff 126; patients, 664; total Bilibid Hospital 810; civilians in the upper compound, 494; and the records that could be located in the dark.

Leon Ma. Guerrero, Tokyo:

Manila’s fail was announced last night by San Francisco but the Japanese press still has the Americans at San Fernando, 70 kilometers away.

February 6, 1945

Ike Thomas, Old Bilibid:

At 6:00 AM opened hospital headquarters at the Ang Tibay shoe factory, and awaited orders. Ward surgeons and corpsmen continued to care for the patients who had been under their care at Bilibid. Ordered to return to Bilibid because of better sanitary facilities and quarters. Upon return found Bilibid had been looted, surgical equipment wrecked, typewriters, food and personal possessions, stolen or destroyed. Cases of medicines broken open and looted but the bulk of the Red Cross medicines in Bilibid were intact. Many records were either stolen or inadvertently destroyed by the Filipinos who had been employed to clean up the wreckage. Had our first American chow this AM and it was as good as we thought it would be. Canned ham and eggs, a prepared cereal milk, “K” biscuits, butter, jam, coffee with milk and sugar, cigarettes and matches.

Warren A. Wilson, Old Bilibid:

Fr. Juan Labrador, OP:

Gen. Basilio J. Valdes:

At 6 a.m. left General Head Quarters with Major General R.J. Marshall, Major General Stivers, Colonel Egbert for Manila. Arrived 10 a.m. Fighting still going on. Found five dead Japanese in front of Tata’s house. Many dead Japanese in the street. Went to R. Hidalgo Street. Prayed at Rita’s tomb. Saw my family.

February 7, 1945

Ike Thomas, Old Bilibid:

Reorganization of hospital as it was before the evacuation. Water pressure extremely low, finally no water. Rations and water requisitioned from Santo Tomas. Philippine Civilian Affairs unit #2, took over mess and continued cleaning up of Bilibid, employed Filipinos to carry water from 4 wells which the Japanese had had the Americans dig in case of such an occurrence. General MacArthur made a tour through Bilibid, visiting every ward and the civilian area.

Warren A. Wilson, Old Bilibid:

Things couldn’t have ‘gone worse if I had. tried this A.M.; clothes dirty, unshaved for 2 days, the hospital littered with debris & in come Gen. MacArthur & Staff. He was very nice- visited all the wards & the internees, shook hands with dozens, talked to a few of his old soldiers etc. – many cried. There was a battery of news cameramen who took pictures of us everywhere as the Gen. & I led the parade.

Hired Filipinos who cleaned up the area, PCAU Units # 1 & 21 were set up to feed us tomorrow. The K rations last thru noon, then B ration which we will cook on our old wood stoves tonight.

Gen. Basilio J. Valdes:

Wednesday. Back in General Head Quarters to report on conditions in Manila.

Leon Ma. Guerrero, Tokyo:

The Japanese press has now been allowed to reveal that the United States army entered Manila on the 3rd and that fighting is now going on within the capital.

The news of street-fighting in Manila plunged us all into deep anxiety. “The Filipinos will never forgive for this,” I told one of our interpreters. “The Americans declared Manila an open city in 1942 and withdrew without fighting. Why couldn’t you do the same?”

He was decent enough not to argue about ”blood-letting tactics”; he grew thoughtful and said nothing. Later he came up to me with a Japanese newspaper. Japanese marines, he said apologetically, were doing all the fighting; the army had withdrawn according to plan but the navy had refused to cooperate.

February 8, 1945

Few people walked out in the streets because of the shelling. The shrapnels fell like scattered stones on rooftops. By midnight shells came nearer. Frank and Josie got up and brought Bobby down. Baby and I followed. It was damp and cold at the landing of the stairs. But we spent the rest of the night there. Frank brought a small suitcase and foodstuffs in case we’d have to run. Then I went up to get more blankets but when I reached the top of the stairs I couldn’t move because I was afraid. But I ran into the room, pulled the blankets and ran down the stairs. The cement steps where we lay were so cold and my bones ached. Frank put an oil lamp and played with cards to keep awake. I slept very little.

Warren A. Wilson, Old Bilibid:

The PCAU Units – Capt. Green & Maj. MacKinsey – fed us from their gasoline ranges this A.M. There is much griping about “seconds” from the pts. They can’t realize that they can’t eat a full messkit of stateside food as they would with rice.

There was much artillery fire on our part the last two nites with same return of it; hence, there has been little sleep & everyone is jumpy. Several psycho cases were hanging on the bars this A.M. like a bunch of monkeys. They started a hunger strike, said the Americans were starving them. I called Col. Allen, surgeon 14th Corps who promised to evacuate them to Tarlac Tomorrow.

Fr. Juan Labrador, OP:

Gen. Basilio J. Valdes:

Returned to Manila with food supplies for the family. Saw the destruction by three direct hits on Tata’s house by six inch Japanese shells. Five hits on the garden. One neighbor killed, several were wounded.

Leon Ma. Guerrero, Tokyo:

A ranking officer from the war office had dinner with him last night. With the help of numerous military maps he took the trouble of bringing along, he explained Yamashita’s strategy in the Philippines. His version was substantially that given in every newspaper in Tokyo: a strategy of “blood-letting” or attrition from mountain positions dominating Manila, Clark Field, and the gate to the Cagayan valley in northern Luzon. Cagayan will be Yamashita’s Bataan.

In the diet the fall of Manila led the lower house to pass a nagging resolution calling on the Koiso government to get going.

February 9, 1945

We awoke hearing the rumbling of tanks. We thought they were American tanks but we were mistaken. We spent the whole morning downstairs. We only went up in the afternoon but were alert and ready to run down, whenever a shell burst. The time passed so slowly. How dreary! We ate early and decided to sleep on the cement steps and the landing.

Around 10 p.m. we heard a big commotion. There were two big fires, one in Irasan and one on Leveriza St. All the people were running back and forth carrying their possessions, and piling them up on the sidewalks. The streets were noisy and crowded with people talking and running with their belongings. Frank brought Josie and Bobby home and told Baby and I to watch the house. We were so afraid. We started folding blankets and packing. Frank came back with the others from home with a pushcart. They made several trips. Frank and I brought down the refrigerator with Baby putting a sack underneath so we could slide it down the two flights of stairs, into the yard and on the sidewalk. But the fire was getting nearer so we left it and saved the other things. From home we watched the houses burn one by one…

Ike Thomas, Old Bilibid:

Reorganization well under way. Rosters about completed. Records show that on Feb. 6, 88 patients were transferred to Santo Tomas which is better equipped to handle seriously ill patients: 3 patients AWOL. 8 mental patients transferred this date to Tarlac. 11 additional patients to Santo Tomas because of family there or desire to remain in the Philippines.

Leon Ma. Guerrero, Tokyo:

The Japanese are blaming the Americans for the destruction of Manila. A Domei dispatch carried by the Mainichi today quotes the spokesman of the Japanese forces in the Philippines as follows: “With a view to saving the traditional cultural establishments of Manila from the havoc of fire and to prevent innocent inhabitants from suffering untold distresses, the Japanese forces in this city (Manila) had beforehand removed or destroyed the important military facilities and taken away the munitions elsewhere. Leaving only a small force necessary for the maintenance of order, we had withdrawn our main strength from Manila. This step was endorsed by the Philippine government which also moved from Manila to attend to administrative duties so that the present city of Manila should be considered a mere cultural city without military or political significance. “Acting from political motives,” continues the spokesman, “the enemy American forces set an excessive strategic value on Manila…. Without regards to the means employed, the Americans behaved in such a manner as to force street-fighting in Manila. The bandit units nurtured by the Americans beforehand, as well as ill-principled men, have taken advantage of this opportunity to precipitate the city into a condition of tragic and horrible misery. For this act of robbing a free nation of its welfare and happiness, the invading American forces should be held responsible.”

Meantime San Francisco accuses the Japanese of burning and blowing up the downtown business center, entrenching themselves in pillboxes in all big buildings, massacring political prisoners in Fort Santiago, holding the entire population of the old walled city in hostage, and wreaking the most savage and unspeakable vengeance on the Filipinos within their reach. The burned and mutilated corpses of the victims of mass executions have been found in the portions of Manila taken by the Americans. It is the story of an army gone mad in the last agony of desperation, looting, burning, raping, killing, torturing every living thing within its reach, obsesses by the ferocious determination that nothing shall survive it.

For us it does not even matter, not any more, who is telling the truth. We are conscious only of a vague, impalpable, but oppressive and inescapable horror, like a poisonous fog — horror, tortured anxiety, fear, a dark anger at the whole of life, a nameless bottomless pity that pulls and wrenches us toward those we love, those we know, and those we do not know, in our burning and dying city beyond the horizon. We have not yet the heart to listen to the evidence, to fix responsibilities, to apportion the blame, to concern, to hate. We can only think in terms of a faceless ruin, death with a hidden visage and an impartial hand, blindly reaching out and striking down and squeezing and tearing — whom? One of us has a wife and six children in Manila: another has a father and mother, brother and sister; each and everyone of us has left someone behind. What has happened to them?

February 10, 1945

When it got bright we started fixing our house. We were preparing the whole day to run away. For my knapsack I got a nepa bag and put one change of clothing, my veil, rosary, and some clean strips of cloth in case anyone got wounded. Mama gave each of us rice, red beans and some money. We also were given a tag with our name and address (613 Remedios Malate, Manila) written in India ink. We pinned it with our blessed Miraculous medals. We were never to remove it.

We packed our pushcarts with food, clothes and cooking utensils and left one empty for the children to ride. The shelling was getting worse and worse, so that we could not even go outdoors to get water from the well.

Ike Thomas, Old Bilibid:

2 additional patients transferred to Santo Tomas, 1 Medical Department Sgt. Placed on DS at Santo Tomas (wife there). 108 patients not able to make 170 mile ride, transferred to Quezon Institute. Remainder of patients and Staff transferred to 12th Replacement Battalion, APO.Transported by 14th Transport Company. Left Manila at 2:30 PM, arrived 24th Field Hospital, Camp Del Pilar at 5:30 PM and were fed and rested. Left one patient, Pvt. Heather (British Army) there due to inability to continue trip. Arrived 12th Replacement Battalion 1:30 AM. The Bilibid hospital unit ceased to function as a unit upon leaving Bilibid. This report closed out as of midnight Feb 10…

Leon Ma. Guerrero, Tokyo:

The Japanese were buoyant this morning. All the vernaculars have headlined a delphic boast from Yamashita: “The enemy is in my stomach.” It is, I suppose, the equivalent of the American “It’s in the bag”. The immediate unanimous but private reaction of the Filipinos here was: “He’ll have indigestion.”

February 11, 1945

We had breakfast and started doing our housework but once in a while we would jump down the trapdoor to the dugout because of the shelling. Biring and her husband decided to butcher their pig and we all helped. Mama and Biring fried all the pork chops, made adobo, and salted the rest. We were in the shelter most of the time. Then a bunch of Japanese soldiers stopped in front of our house planting dynamite. We shivered! We noticed a fire nearby getting bigger and bigger. It was the Masonic Temple in Vermont and Taft burning and the wind was blowing the fire towards us. Burning particles were flying again, Papa and Frank thought it would be safer under the Gonzales’ house which was concrete, so they broke down the stone wal. We all ran under the Gonzales’ house. Then the Japanese passed on Wright st. with rifles ready to shoot. We lay flat but since there was no dugout we went back home.

Suddenly bunches of people came running towards our house. Some were wounded, some were carrying possessions, many were hysterical. They said the Japanese threw hand grenades at them in their shelters. They got separated from their families. We gave them water to drink and they ran out again. The fire was coming nearer and the smoke made our eyes water. It was time to go. We pushed our pushcarts and made trips back and forth. Among last night’s burned ruins we found many little roofs with refugees under them. Frank found an empty corner of a house in Florida st. The walls in one corner still stood and we pulled a piece of zinc from among the ruins and placed it across the walls. We put our bundles of clothes on the hot debris and sat on them. We could not save all our things as the Japs came to patrol. We could hear the crackling and we could feel the heat of the houses burning: Five of us had to go to another place under a small table. Our legs were popping out. We could hear the kids arguing and later two more came with us. At dawn we started for home cause our house didn’t burn after all.

February 12, 1945

…The houses all burned immediately whenever a shell hit. Our house, the Hemingway’s, Bagasan’s, Amador’s, were all burning now. It was getting hotter and hotter. Then the smoke came under the house as the Gonzales’ house caught fire too. We crawled to the next house on the left. There was a shallow hole and it was soft and sandy soil so we started digging with our hands just so we could lay flat on our stomachs. We found a mattress which we used to cover our bodies. We stuck out our heads and watched the people passing on Wright st. They were dragging their wounded. Then we saw some of the Amadors walking. We found a bottle with brown sugar and gave the children some. The heat became intense. We had to go. When we came out into the street it was very quiet –not a living body, all were dead. We could not turn right to go to Remedios and Florida as the heat from Amadors’ and Montes’ house made the road like an oven. We turned left. We stumbled and walked nervously holding on to each other, afraid of stepping on parts of dead bodies. We reached Vermont and the Vasquez house but they didn’t let us in because it was a Red Cross headquarters and none of us were wounded. We reached Tennessee st. and turned left. At Georgia st. we saw four Japs and they saw us! We ran fast into a building. We hid a while but were afraid there might be Japs in the building. Then Nong peeped and they were gone. Thank God! We turned left on Georgia and came to Vermont and turned right till we reached the corner of Florida st. at last! Two blocks away was our shelter among the ruins but it was too hot to pass. But if we stood there, the Japs might see us. So Nong thought we’d better dash through the hot street. Irasan was burning. We saw many dead bodies. Most of them we knew. We came near the place where we had our shelter. It was very, very quiet, not a soul. There were dead bodies all over the place. When we came to our place what a mess it was! We came nearer and called Frank, nobody answered. Then we called Chars and Ini and Chito but nobody answered. We approached reluctantly. We saw Ini and Frank but we saw blood. We didn’t know who was wounded. It was Chito! We did not expect it to be him. When they saw us they were so surprised! Most of us cried and cried. They said they saw our house being hit directly and then bursting in flames and they were sure we were all dead. They told us that Chito was sitting and a shrapnel went through his leg, took out a piece of his hand and hit the other leg. When Chito heard that his friend Ding-ding died, he cried and cried.

The shells never stopped one after the other and when they burst the smoke and ashes came under the tables and we were all fainting one by one. There was a man with one arm gone and he was delirious and quarreling with another man under a roof nearby. The judge was drinking and he was desperate and crying. He said his wife and all his other children died. He told us to take his daughter if he dies. Chars ran out to look for medicine and came back with a sleeping tablet from Mrs. Kalaw but the Japs almost saw her on her way back. A man just pulled her back as she was beginning to cross the street. Then the Japs came to the street and we had to stop the children from crying and had to remain very quiet. Again all the shells fell in our vicinity and debris, stones and shrapnels were falling all over. The people were screaming and crying around us. We clung to our medals and prayed and prayed. One shell fell right near us and we choked and coughed and most of us were fainting and we could see figures getting out of our shelter.

Maximo went to get water, it tasted like gunpowder and smelled like the dead. We put a few drops of listerine in it and drank one sip each. The shelling never stopped the whole night.

Leon Ma. Guerrero, Tokyo:

A feeling of depression has overtaken the Japanese. Everyone expected Yamashita to do something big in honor of yesterday’s festival. Kigen-setsu, empire foundation day. But nothing happened.

February 13, 1945

…Near noon planes came and dropped bombs near the rotonda. We just prayed and prayed “Miraculous medal save us,” over and over again. There were shells again and no more lulls. Just shells and bombs and shrapnels. We were just waiting to die, we thought it was the end of the world! People ran past our place. One man was carrying a turkey and one was dragging a goat. There was an old man with a dying baby in his arms and Nong ran out to baptize the baby. We found a bottle of brandy and we all sipped so we’d stop fainting. Then we saw clothes of the Japanese hanging in poles and we did not know what that meant and we were so afraid. Then the rice was cooked, we ate. The Amadors opened red pimentos and asparagus and even fruit cocktail.

Then there was a lull and we saw people walking with their hands up. They told us that the Americans were on Taft ave. and the guerrillas told them to go there. They told us to go too because this was going to be the battleground. We watched them but couldn’t decide whether to follow or not. Then Niño our neighbor, came to tell us that Taft until Paco was liberated already. Now we really had to go. Joseling told us to leave him as he cried from pain when he was moved. But Niño and Tony carried him into a pushcart. We put a board over the other pushcart loaded with things and put Chito on top. In the other one we put the children. We also brought the mattress on top of the table. There were many guerrillas directing the people… They told us to hurry up. We recognized many of them from Irasan and also the man selling bananas in the market. There were big holes in the streets and electric posts and wires and we had a hard time pushing the pushcarts.

When we reached the corner of Taft and Remedios we thought we saw some Japanese with dark green uniforms and helmets and guns. But they were big and as we approached they weren’t Japanese. They were Americans! Americans! We were so happy! Some people ran to them telling them what happened. The other Americans were in foxholes with their machine guns ready. A Spanish lady ran and kissed the hand of one of the American soldiers. The people thanked them over and over again. Some people gave them bottles of wine. Then we came to a big crater and we could not let the pushcart through. So we just carried the things.

Then we went to the first aid station among the ruins. George and Joseling had been treated and lay on the cement. Then I lined up carrying Cila and holding Pichy. We were way behind the curved line and watched the people being treated. It was very frightening. There was a man with stones and clothes stuck to his back wounds and the doctor had a hard time taking out his stuck shirt and he was in so much pain. The doctor amputated fingers and removed little shrapnels but not the ones way inside that needed an operation. The doctor ran out of medicines and we had to go away without Pichy and Cila being treated. The Philippine Red Cross nurse made soup for the wounded lying among the ruins. We put Pichy in a pushcart and she was crying very much thinking about her parents who died. An American soldier cheered her up a bit. There were several American soldiers and they also carried their wounded and dead. We found the rest of the family in a ruined house where Madre Maria Sausa brought them and gave them corned beef. The American soldiers told us to walk on and we’ll be picked up by trucks.

We walked on and waved at the trucks that passed by but they only picked up those who were wounded. We met a friend who said Chito, Papa, Chars, Nong and Toots were headed for Malacañang. Everyone told us to go to Malacañang cause there were bread and apples there. Then we sat in front of a Pandacan schoolhouse waiting for a truck to take us to Malacañang but it was getting dark so we joined the crowds going to the schoolhouse. It was full of refugees, so we slept under the schoolhouse. We put the mattress on the ground for the children. I slept on top of our bundles of clothes so they wouldn’t be stolen. We opened the can of corned beef but we didn’t care to eat. We were so very tired and sleepy.

February 15, 1945

Fr. Juan Labrador, OP:

A provost official –one of the many new friends with whom we had been fraternizing– offered me a trip to Manila in his jeep. I accepted willingly, in order to have a personal knowledge of what is happening in the Capital.

We left at 7:00 in the evening and we were at Balintawak by midnight. It was a very fast trip by the standards of these times. All the bridges had been blown up by the Japanese and had been replaced by pontoon bridges constructed by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers. The way these soldiers are working is admirable.

We did not attempt to enter the city. Shelling was very intense. We spent the night in the jeep, parked in the middle of thick grasses. I did not sleep a wink as I watched the shrubs and grasses move, not by the wind but by some snipers. I heard the thundering booms of the guns and the whistling flight of shells as they rent the air over our heads, while in the city, vast columns of smoke were rising and big fires were raging.

At the break of day I entered the main gate of the University for the first time in three years. I found the Seminary filled with refugees. Most of them came from this northern sector of Manila where several blocks of houses had been burned by fire caused by Japanese, or started by Filipinos who had been paid or forced to burn them. The Education building has been converted to a hospital for civilian casualties who came from the south in uncontrollable influx.

The internees are still living in the main building in other smaller ones. They were huddled in rooms and corridors, but free, happy, well fed and properly clothed. Many of them are gradually recovering from their skeletal countenance and their cadaveric paleness due to starvation under the Japanese regime.

February 18, 1945

Fr. Juan Labrador, OP:

The evenings are a nightmare. They bring a rosary of shocks produced by powerful guns which, from New Manila and Grace Park, strike at Ermita and Intramuros, shaking the air, the earth, the doors and the nerves. Projectiles fly over our heads, whistling their funereal song of destruction. We cannot look at them: we can only follow their trajectory with our ears. Mortars from the Far Eastern University and the Osmeña Park batter the eardrums with metallic poundings. Machine guns, crackling like coffee grinders –Tac, Tac, Tac, Tac, Tac! rattle in, from behind, at the sides, in search of Japanese snipers. The fires from the Japanese side which reach our vicinity add to the confusion. A mortar hit the tower of the main building where the Americans had set up an observation post, and from which General MacArthur observed enemy lines this morning. Others fell on the Education building and on the intern’s garden. However, there were no casualties.

But more shattering than the dissonant harmony of war engines is the news about the tragedies suffered by survivors who escaped from the southern part of the city. The accounts are so terrifying and so macabre that my spirit was filled with infinite bitterness, and I wept with tears of pain and indignation. From the sadness and sympathy arose an impotent anger against the infernal forces which vented its desperation and hate among the civilian populace. So many families of acquaintances and friends exterminated. So many mutilated. So many who escaped the Japanese hell lost everything but their lives. The hospitals –the few old ones which still remain, and a number of improvised ones– are filled with the wounded, whose hands or feet or body are perforated with bullets or shrapnels. Many are searching desperately for their lost loved ones. Manila is a picture of sadness impossible to describe.

The Japanese plan of attack against the defenseless Manilans is as diabolic as it is organized. Its defense strategy consists in positioning themselves behind the civilian residents, and as the conquerors advance within a dangerous distance, they flee or burn the buildings and retreat a few blocks backwards. They machinegun the residents who attempt to put out the fire or run for their lives. The only way to save themselves is to jump into a ditch and stay there. Anyone who raises his head is fired at. They stay for four to eight days without eating or drinking, tortured by a rabid thirst. I was told of cases where persons, dying of thirst, drank human blood mixed with mud.

In many cases, the soldiers would approach the ditches and kill the occupants with bayonets. That was how they killed the De La Salle Brothers –Irish and Germans–, the Padres Paules of San Marcelino among whom were Fr. Visitator Tejada and Fr. José Fernández, and Irish Fathers of Malate, together with the evacuees in their buildings. The same fate fell on fifty others, almost all of whom were Spanish, who took shelter in the Spanish consulate. Aside from being attacked with bayonets, they were also attacked with hand grenades. Only a little girl escaped alive.

Another way of liquidating the people is by herding them into a house and setting fire to it, at the same time hurling hand grenades inside. Anyone who attempts to escape is shot.

There were frequent cases where soldiers threw hand grenades into the ditches or air raid shelters, and those who attempted to escape were hunted like animals. In order to economize on bullets, the assassins usually would tie entire families to post or pillars and kill them with bayonets. It was not rare that a hundred or more persons were lined up and machinegunned.

In the shelter at the German Club, some four hundred persons of different nationalities were attacked and massacred by drunken soldiers. Only about half a dozen escaped. The young Enrique Miranda, son of Telesforo Miranda Sampedro, told me that his mother and five brothers were taken by the Japanese. He did not know what happened to them. We learned later that their bodies were found mangled –those of his two brothers, in the street. Enrique said that he was made to kneel down and they hit him on his neck. He lost consciousness. He came to his senses when a soldier was prickling him with the point of his bayonet to find out if he was already dead. He tried to bear the pain and feigned death. The soldier covered him with earth. He was able to bore a hole through which he breathed. Later, he squeezed himself out and, bleeding all over, he hid among the stones until he was found by the Americans.

In Singalong, the Japanese marines gathered the men to send them on forced labor. The men were made to line up and were herded on groups of ten into houses where their heads were cut off. As those who were in the streets could not hear anything, they entered the houses confidently, believing they were only to register their names. A son of Mr. Ynchausti, among others, escaped, but was badly wounded.

It was providential that in almost all cases, someone among the victims was able to escape and was able to relate the fate of his companions.

The Japanese installed machineguns on the towers of the Paco and Singalong churches, not to counterattack the approaching Americans but to mow down the residents –men, women and children– who might attempt to flee. The Remedios Hospital and the San Andres agricultural school, where thousands of escapees had taken shelter, were shelled with mortars and even Japanese anti- aircraft guns. Many, however, were also killed by American bombs…

February 20, 1945

Fr. Juan Labrador, OP:

Let us shift our view for a while from this scenario of horrors, and take a look at the Manila of the liberators, as it was narrated to me.

The American High Command has not failed to notice the vandalistic scheme of the Japanese in the attempt to save themselves with the City and with the residents of the Capital, of converting the city into a heap of rubble and killing all the inhabitants, starting with the internees in Santo Tomas.

This was confirmed by some well-meaning Japanese. The program of destruction, murder and suicide, which is being launched in the southern zone is also being planned for the northern section. Written orders to this effect had been found and brought by the guerillas to the headquarters of General MacArthur.

The Japanese did not expect the American advance forces at the approach to Manila until about the 6th or 7th of February, so that on the 3rd, it was supposed that the front line was about fifty kilometers from Balintawak. On the eve of this day, at about 8:00 o’clock, the priests and internees of Santo Tomas heard tanks penetrating through España street. They posted themselves in front of the gate of the University campus. Lights went on and illuminated the buildings. Jubilant shouts and outbursts of joy were heard from the detainees who barely perceived that their liberation was forthcoming. In a few moments, volleys sounded from within and without the campus. The tanks and machine-guns replied. A number of soldiers and guerillas who served as guides fell, among them Manuel Colayco and the young Kierulf who died later. Absolute silence. Total darkness. Then the lead tank barged in through the fence into the campus, followed by seven others and by twenty trucks loaded with troops, the first with lights on, the others without lights. They reached the front of the Main building. Another shout and welcome from the prisoners. A new discharge of fire from the Japanese defenders, and then another sepulchral silence. The monstrous caterpillars kept advancing along the sides of the building until they were positioned one at each alley. Some internees started fraternizing with the liberators and received their first cigarettes, biscuits and canned goods. Other tanks positioned themselves towards the gymnasium and the Education building.

So passed the night.

At daybreak, the capture of the Gymnasium. There were Japanese soldiers there guarding the prisoners. But they fled into the darkness. The Americans scoured the place fearing that the Japanese had hidden themselves in a nearby grassy area. But they could not be found.

Later, the conquest of the Education building. There were some seventy Japanese soldiers dispersed behind the detainees. The Americans appealed to the Japanese to surrender. No response. They were promised to be let free out of the campus. Negative. They were promised to be transported with their arms up to the Japanese lines. The Japanese conceded, and in two trucks they were transported up to the Rotonda.

That was how the campus which had imprisoned some four thousand internees, and, incidentally, occupants of the seminary, was recaptured. But they were so far the only liberated buildings together with those near Malacañang. The rest of the city, during the night of the 3rd and the whole day of the 4th, were still not re-occupied, except in the sense that the liberators were almost in the middle of the capital. But there was only a handful of American troops who had entered the enemy territory. It was a blow which was as bold as it was daring.

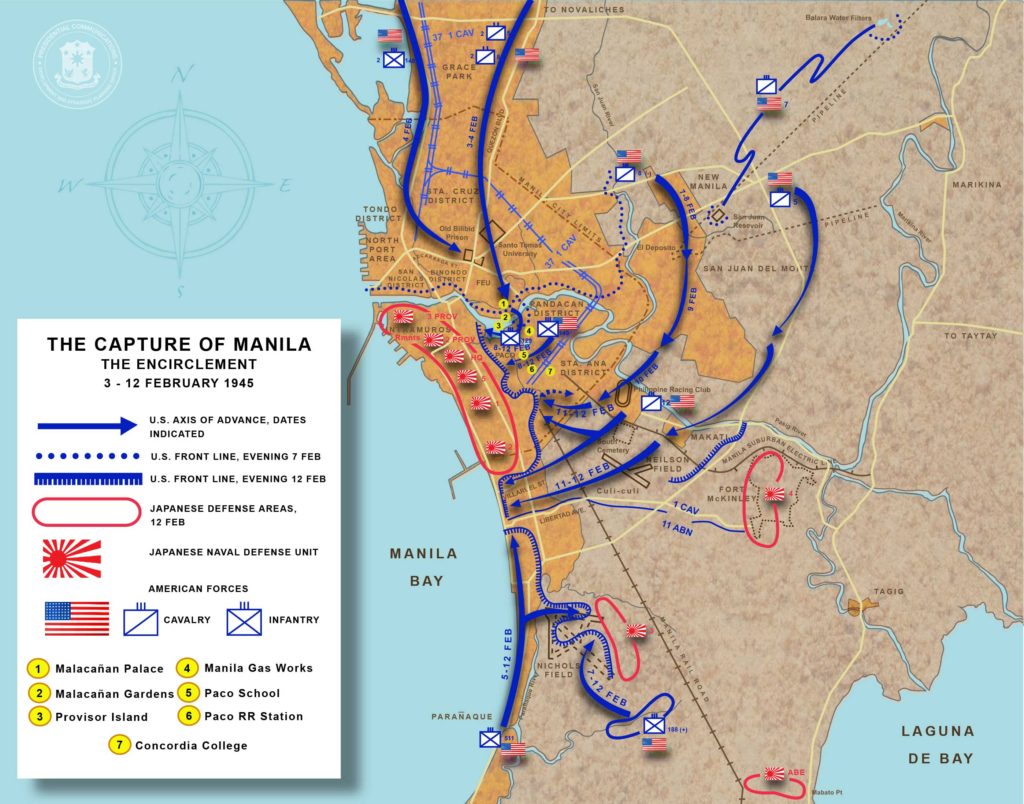

The First Cavalry, dismounted but motorized, had left Cabanatuan two days before. As it was left behind forty kilometers from the main body of the advance forces, it opened up a road through Novaliches and Balintawak, Rizal Avenue and Quezon Boulevard, spitting machinegun shells against Japanese troops and trucks they encountered along the way, and penetrating almost into the heart of the city. They were about a thousand men surrounded by Japanese forces bent on defending the city. Their audacity rattle the enemy. If the Japanese had a foreknowledge of the small number of the infiltrating forces, and had they organized a rapid and decisive attack on the Americans, the liberating forces would have been annihilated. They had thirty-six hours to do it and they faltered. Thus were saved the First Cavalry, the American prisoners and the north of Manila.

In the morning of the 5th, when the Japanese initiated a disorganized attack from España street, from Far Eastern University and from Bilibid, the 37th Division had already penetrated the City from the north and from the east, joining the liberators of Santo Tomas, and jointly re-occupying Quezon City and the sector of Manila north of Azcarraga. Malacañan and Bilibid, where some one thousand two hundred seventy war and civil prisoners were detained including those who came from Baguio, were also liberated.

The Japanese began their program of destruction. They placed cans of gasoline and mines in big buildings of the Escolta, and surrounding streets, and destroyed fire engines and equipments. They blew up and burned buildings, and the uncontrollable fires razed the whole of the commercial district from Azcarraga to the Pasig.

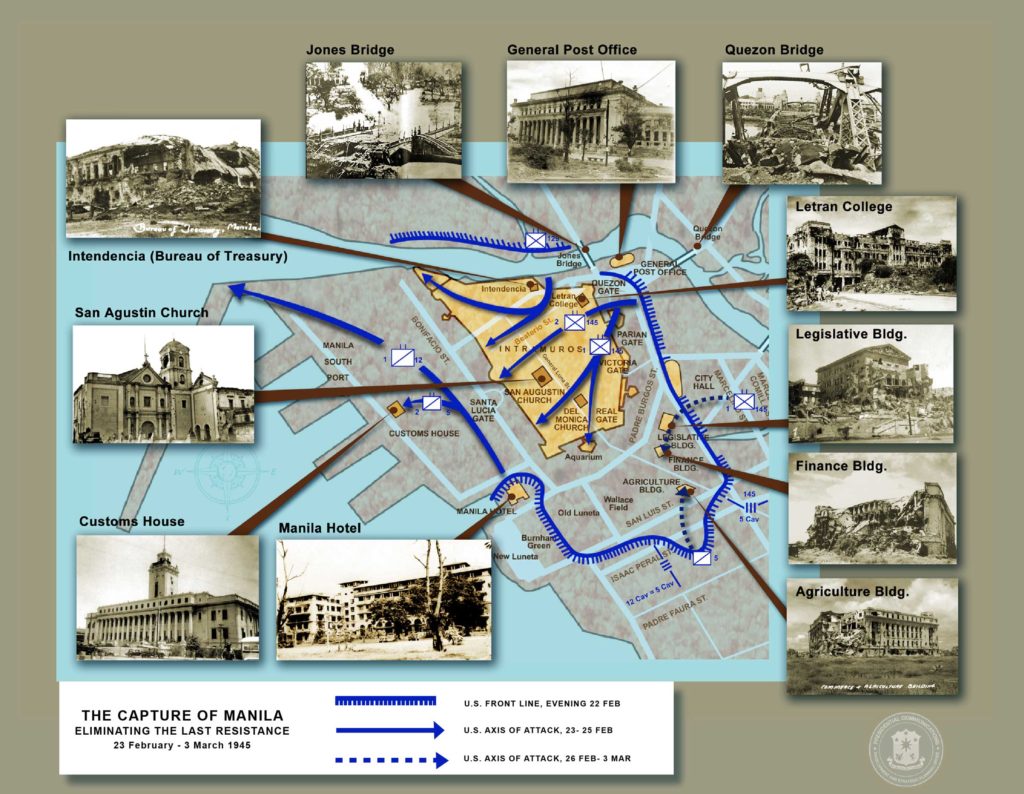

On the 6th, the Americans positioned themselves along the Pasig River. The whole northern region was thus liberated, although small groups of Japanese continued burning clusters of houses and forcing the Filipinos under their control to do the same. On the 7th, the battle of the Philippine General Hospital shelled the north of the city, especially the University of Santo Tomas which suffered fifty to sixty hits, mostly on the construction of P. Ruaño, the principal target of the Japanese guns. There was a lamentable number of casualties, some forty dead and three hundred wounded among the recently liberated. In the Education building, five were wounded. In the Seminary, there were only two slight casualties, a priest and a househelp. The attack lasted forty-eight hours.

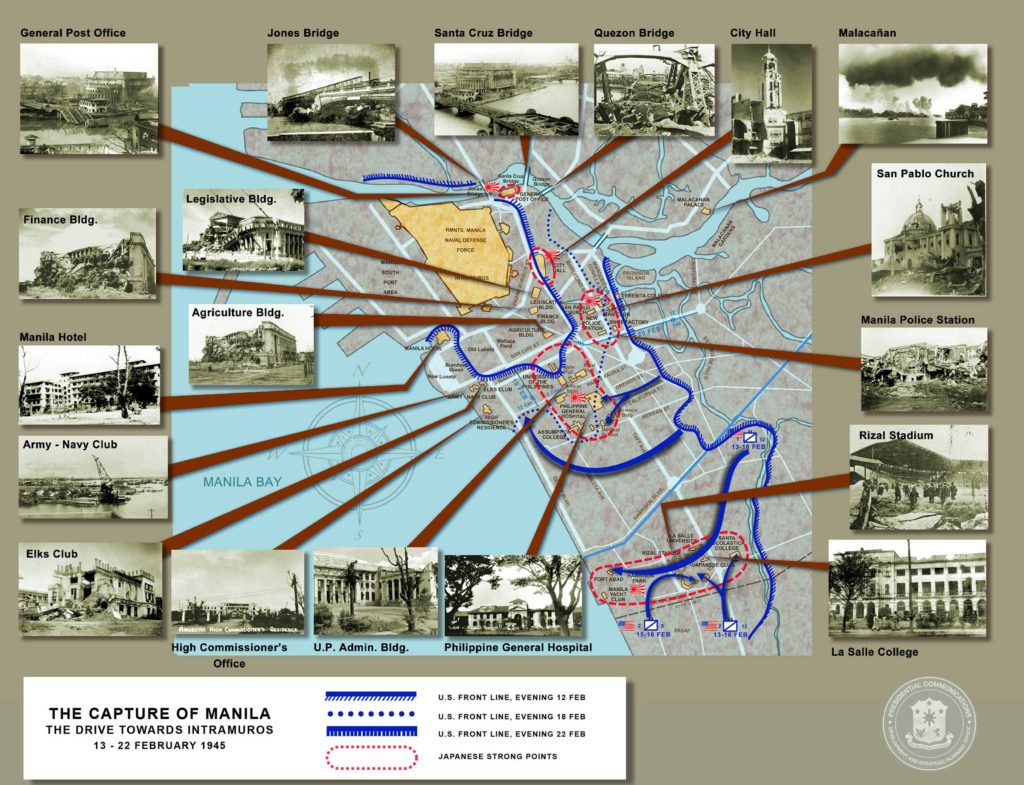

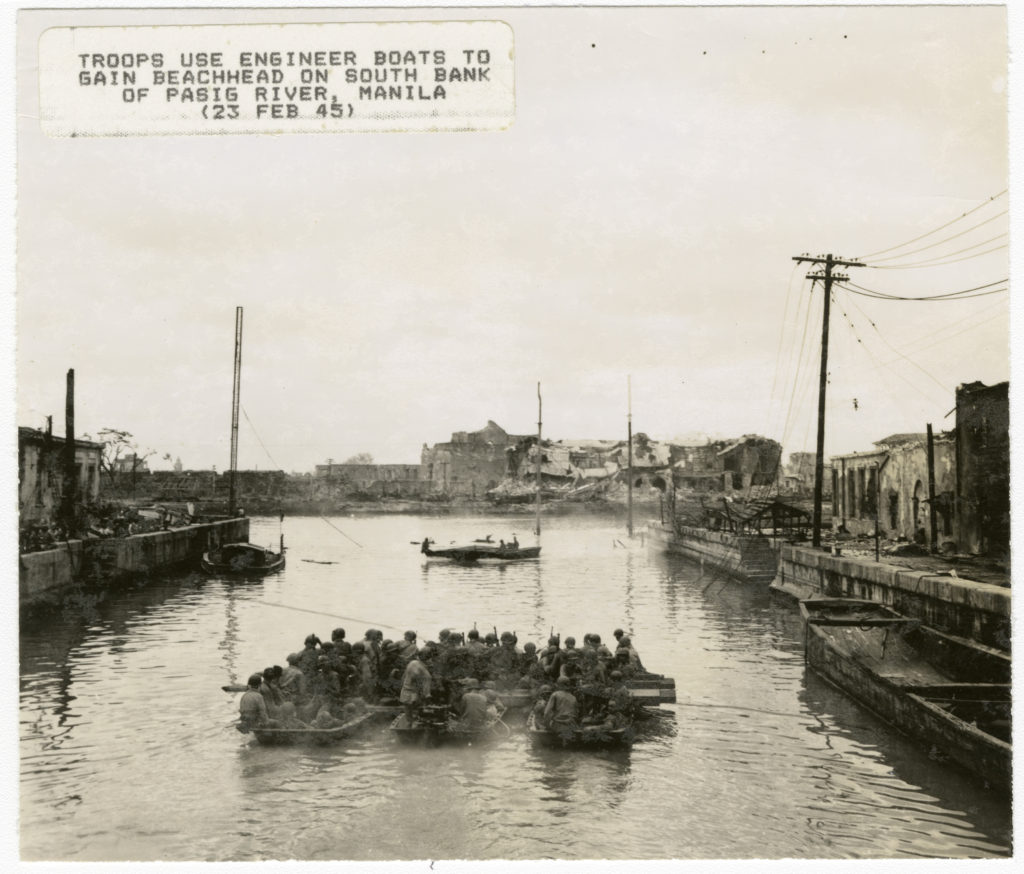

The Japanese blew up the four bridges across the Pasig. On the 7th, further beyond Malacañan, five battalions of the 37th Division crossed the river in tanks and amphibian trucks and, after fierce fighting, they opened up a path through the cleared areas of Paco and the Gas factory. The Japanese defenders started converting each house and building into a fortress, burning them and killing their occupants when they had to abandon their posts.

In the meantime, the 11th Airborne Division, after a successful landing in Tagaytay, advanced until they joined the first wave at the southern approaches to the capital through Baclaran and Nichols Field. They mopped up these areas, destroying one hundred Japanese fighter planes and capturing seventy-five pieces of artillery and one hundred and twelve machineguns. They then proceeded towards Pasay. The cavalry made a second crossing of the Pasig through Sta. Ana. After a bitter house-to-house fighting, they drove back the Japanese from the hippodrome and from Makati. They then joined the 37th Division near the Paco Railroad station, and the 11th Airborne at the north of the Polo Club.

With these reunited forces, the Japanese defenses in Manila have been isolated and pushed back in Singalong, Malate, Ermita, Paco, Intramuros and the Port Area. American advance is slow. They are not employing the air force and they use the artillery with moderation for the sake of the civilians. The soulless defenders entrench themselves behind houses and concrete buildings, devoting their time more to arson and murder rather than in fighting the liberators. The Americans, in a rapid execution of strategy, were able to save some seven thousand refugees at the General Hospital before the vandals could effect their diabolic plans.

February 21, 1945

Fr. Juan Labrador, OP:

Weeks have passed since the start of a thorough attack on the south of the Pasig. The battle was bloody and although there were heaps of Japanese fatalities, there were very few prisoners. American casualties were heavy. The front line ran along behind San Luis Street, behind the Casino Español, City Hall up to Quezon Bridge. American artillery is demolishing the palace of the High Commissioner, the Army and Navy Club, the Bayview Hotel and the government buildings east of the Wallace Field. City Hall and the Post Office building also received their share of shells.

The shelling of Intramuros has begun. The Japanese are using the walls as mortar positions and defense walls. They launched a mortar attack on the tower of the UST main building, and another on the Education building.

American firing during the day is incessant, and by night, formidable. They are pulverizing the buildings between Taft Avenue and Burgos Street, and those of the Luneta. The clouds of smoke rise like a black torrent surging from the horizon and enveloping the sky. We are worried about the fate of the residents of Intramuros, trapped within its walls. We can only foresee unspeakable anguish and torture and a bloody agony in the hands of their tormentors.

The number of persons imprisoned is calculated to be around seven thousand, among whom were some forty missionaries, mostly Spanish, and some Filipino and Spanish Sisters.

February 24, 1945

Fr. Juan Labrador, OP:

The final and thorough attack on Intramuros was effected yesterday. After the artillery assault, the most thunderous and terrifying we had ever heard over this locality, armored cars and amphibian tanks crossed the river along that area and landed via Santa Clara in the Cathedral plaza, advancing up to the center of the Walled City. At the same time, other units hopping through the rubble of the walls at the south of the Victoria Gate, despite heavy casualties, penetrated along the once narrow streets now in ruins, until they joined the amphibian forces.

Towards the afternoon yesterday, the first liberated residents of Intramuros arrived. I talked to some of them. They were completely rattled and shaken not because of wounds or weakness but more because of the horrible scenes that they witnessed and the savagery which they had been subjected to.

The most coherent account was made by Fr. Belarmino de Celis of the Convent of St. Augustine which I shall narrate here as a typical example.

On February 8, all male residents of Intramuros from fourteen years up were taken to Fort Santiago. The women and children were herded into San Agustin Church and the Cathedral. Then the Japanese made a thorough search of all houses, placing dynamite in strong buildings to blow them up or burn them later. In prison, the Spaniards were separated from the Filipinos who numbered about two thousand. After a week without food and water, they were sprayed with gasoline with the use of a hose. Many thought that it was water and therefore opened their mouth to quench their thirst. They were then burned alive. A number of them, driven mad by the fire and by thirst, were able to break the bars of the cells and jumped into the river. But they were machine-gunned by the sentries, and only two, a Filipino and a Spanish youth, were able to escape. The young Spanish, Luis Gallent, with a fractured dorsal spine, swam to the opposite bank and was picked up by the Americans.

The Spanish group (among whom were forty missionary priests) was detained in another room, where they were so crowded that there was no room to fall down on the floor. The food sent them by the women from San Agustin was appropriated by the Japanese. On the 10th, they were returned to the San Agustin Church. Both in prison and in this church, five Filipino spies who confessed their guilt, were mixed with them.

On the 18th, they were moved out to a warehouse in front of Sta. Clara, after the women were assured that the men were being transferred to a safer place, and only for a day or two. The evening of the following day, they were made to line up in the street, guarded by an additional contingent from Fort Santiago, and led to some wide concrete shelters constructed in the yard of the old headquarters in front of the Cathedral.

With their repeated and courteous protests that measures be taken to protect them from the intense shelling, they were made to enter the shelters. In one shelter, eighty were herded, in another, thirty-seven. As the caves did not have the capacity for so many, they made the most of the situation as, after all, the shelling would last only for a couple of hours. When they were all packed up and praying the rosary and receiving the absolution, the Japanese started hurling hand grenades through the port holes of the shelter. Everyone was wounded, each in varying degrees. Some were able to force the door open and attempted to escape. They were met with bullets and laughter. A good number were killed. When the shouting and moanings decreased, the entrance was sealed with earth and gasoline drums so hermetically that those who were still alive died of suffocation.

In another smaller shelter, the soldiers threw grenades through the entrance, and only those near it received the impact. Seven survivors were able to make an opening and got out of the sepulchre alive.

In the other shelter, Fr. Belarmino, with his face and side pierced by shrapnel, noted that he was not seriously wounded, but he was suffocating in that cave and tried to bore a hole at the entrance. But one of the graveyard caretakers detected the hole and sealed it. After a long while, the interred prisoner opened it anew. He had to crawl over the corpse of his dead companions. He could still hear the moanings of some who were in agony. The shells which continued falling all around caused earth and stone to fall and cover the agonizing and the dead. The corpses decomposed and were covered with flies.

Fr. Belarmino was buried alive for seventy mortal hours, dying of thirst and suffocation. On the night of the 22nd, he decided to die of bullets rather than of asphyxiation. He succeeded in removing sufficient quantity of stones and thus create a wide opening. The Father and Mr. Rocamora, the only survivors, pulled themselves, as they could not walk, they crossed the plaza of the Cathedral which was littered with broken glass and barbed wire which opened up new wounds. But they were able to reach the Bureau of Justice building. After a short rest, the priest left his companion who could not crawl any farther and he reached the convent of Santa Clara where he asked for food and water from the Sisters. The Sisters could not give him food or drink as they themselves did not have any. He advised them to leave the convent. They were surprised how he was able to reach that far without having been killed by the sentries and they begged him to go before the sentry returned and killed him. He returned to the Bureau of Justice, searched all corners and found a toilet with the tank full of water. He quenched his thirst and filled a can for his companion. They recovered their strength somehow in spite of the loss of blood, and passed the rest of the night quietly.

Yesterday morning, the siege subsided over that part of Intramuros after a very intense barrage, preparatory to the crossing of the river. There was calm for a couple of hours. Suddenly, they heard voices: “Come on, come out.” From the accent, they knew that they were Americans and they saw the heavens open. The Father, supporting himself on the wall, came out to meet them. But his companion could not move. Three sisters of Santa Clara came. Their convent was a heap of rubble where ten other Sisters were buried. The priest showed the soldiers where his companion was and they took him in a stretcher while he, supported by two soldiers, was taken to another building where he was given food and water. He told them about the two shelters full of people, but they could not cross the Plaza as the Japanese were firing at the Cathedral. He was transferred to the other side of the river and later was brought to the hospital at the UST campus where he narrated to me all these.

In another ward, I visited Fr. Cosgrave, an Irish Redemptorist. He had both shoulders pierced by a bayonet. His account was another typical one among hundreds which could be told.

Fr. Cosgrave, together with sixteen lay brothers, their chaplain and four families were living in an unoccupied portion of the De La Salle College. The four families — of Vásquez Prada, Judge Carlos, Dr. Cojuangco and his politician brother, were composed of thirty women and children, twelve houseboys, aside from the men, a total of seventy persons.

On the 7th of February, the Japanese took the Director, Brother Xavier and Dr. Carlos. They never returned. On the 12th, while the refugees were under the stairs because of a violent shelling, a Japanese officer with twenty soldiers came. Upon orders from the officer, the soldiers poked their bayonets at all men, women and children. Some of the Brothers — twelve of them were Germans — were able to get away and run upstairs. They were chased by the soldiers and were stabbed at the entrance of the chapel, others inside. Those who resisted were shot by the officer.

When the soldiers were through with the orgy, they dragged the bodies and piled them under the stairs, the dead over those who were still alive. Not all died upon being stabbed. Among them were children of two years and less.

At about ten o’clock in the evening, the chaplain, notwithstanding his wounded shoulders, was able to free himself from the heap of corpses and crawl upstairs to the chapel. He administered the extreme unction on the agonizing, himself resigned to his fate, and likewise asking pardon for their torturers. He found other corpses in the chapel. Hiding behind the altar were ten others.

On the following day, the Japanese started blowing up different parts of the College. They tried to burn the chapel, but as it was made of concrete, only the furnitures caught fire. For a while, they feared that the smoke would suffocate them. On the 15th, after four days of natural fasting and slow bleeding, the ten survivors — among them a son of former Speaker Aquino — were saved by the liberating troops.

February 25, 1945

Fr. Juan Labrador, OP:

The civilians who escaped the murderous claws of the Japanese were able to save themselves either fortuitously or through the intervention of some good-hearted Japanese — we have to do justice to some of them who saved others at the risk of their own lives — and always by a providential act of the divine mercy which knows how to counteract the most notorious plans. Both the annihilation of the civilian population and the mass suicide of the Japanese army and people had been premeditatedly planned by order of the Imperial government which wanted to drown national defeat and humiliation in blood.

February 27, 1945

Fr. Juan Labrador, OP:

The last night I spent in Manila was the first that was exempt from the thunder and lightnings of war. I returned to my rural residence, From 7:30 in the morning to 7:39 in the evening — the return trip was not as enjoyable and as fast as when I left. Inhaling dust, I watched the interminable caravan of vehicles going towards Manila. Each time, we stood amazed by the numerous war equipment produced by the Americans and landed here by the army.

Some 25 kilometers north of Manila, I saw by the bridge of Meycauayan a dozen of Japanese prisoners, withered and starved. They had just been captured while awaiting a chance to attack the Americans who would pass by the bridge. Such attacks were frequent — on bridges, in encampments, always at night and suicidal, with hand grenades or bayonets. The damage they caused was insignificant in comparison with what they suffered. But, either on their own will or upon orders, they had to die, killing in the process. It was easy for them to die, but they found it difficult to kill. For what could they do with their antiquated arms against automatic rifles which could discharge thirty rounds or more? They were searching for immortality and they found it. They wanted death and glory — not death or glory — and the G.I.’s gave it to them wholeheartedly. It was an insatiable thirst, this suicidal and destructive fanaticism. It was so irritating, inexplicable, exciting and the cases involving it so typical, crude and frequent that we always tended to deal on this sempiternal topic without exhaustion. And the more we delved into it, the more we found it inexplicable and unpardonable.

In Calasiao, I saw a vast expanse of land surrounded by wired fence. I was told that it was a concentration camp for those captured in the northern sector. The prisoners could be seen walking, working or resting. The police had to be on watch, not to prevent their escape but to protect them from being attacked. They knew that if they escaped, they would not only be unable to find anyone to give them refuge, but they would certainly be cut to pieces either by the guerillas or by their countrymen.

The American Army took few prisoners. The Filipino Army turned in only dead ones. Sometimes the MP’s had to defend the prisoners from the infuriated populace.

March 6, 1945

Fr. Juan Labrador, OP:

I returned to Manila, this time for good. These officers were so accommodating that they were willing to go two hundred kilometers just to please us. But, in order not to absent themselves from their posts during their tour of duty, they travelled during the unholy hours of the night. Never had I experienced such cold weather in the Philippines. It reminded me of Siberia. Our host, a phenomenon that he was a captain at 24 and weighed 280 pounds, had to put on his leather jacket. With my frail body and with my tropical garb, I was shivering all over.

The mountains to the east of Bamban were still shaking under the thunderous pounding of our friends in the 43rd Division. Without giving enough time for rest and the disposal of casualties suffered in Rosario and the road to Baguio, the High Command transferred part of the Division to Zambales and part to Camp Murphy in New Manila for a mopping up operation of Clark Field and Antipolo.

That night, when I heard their cannon rumbling, I whispered a prayer for our liberators, our best friends who up to this time were still with me, the bravest and the most generous.

March 8, 1945

Leon Ma. Guerrero, Tokyo:

On the 8th of every month, which is set aside all over Japan to commemorate the imperial rescript declaring war, Vargas pays his respects at the Yasukuni shrine, where the spirits of Japan’s war-dead are enshrined. Today, after the customary ceremony, he was taken to a new six-foot drum.

“Will His Excellency be so kind as to beat this drum?”

His Excellency did.

“No, No,” the chief priest exhorted. “Harder, beat it harder, hard enough so it can be heard in the Philippines.”

Apparently the drum has not been beaten hard enough. The Asahi complains today that “our crack forces on Luzon and Yiojima are fighting valiantly, causing the enemy much bloodshed, but to our regret the hegemony of the sea and the air is in enemy hands.” And the paper continues: “While our forces have little means of further supplies the enemy is in a position to obtain supplies in rapid succession. Accordingly, in spite of the valiant fighting of our forces, the war situation on both battlefields cannot but be judged unfavorable to us.” The paper then goes on to warn that a landing on the mainland is to be expected.

For its part the government has decided to reopen the diet for a single day on the 11th March “with the intention of explaining present conditions and of clarifying the conviction of the government to cope with the situation.” Another session of the diet will be called on the 15th or 16th “to present various bills.”

As the shadow of invasion and defeat falls deeper on Japan a cold wind of suspicion and hatred for all foreigners rises. The German embassy has found it advisable to warn all its nationals off bombed areas “to avoid disagreeable incidents”. Nor are the East Asians wholly sheltered from this popular reaction. The press speaks openly of the “Bei-Hi-Gun”, the American-Filipino forces now fighting on Luzon. The Philippine Society, in planning its new quarters, has notified the embassy that shelter will be provided for Filipinos “in case of rioting”. But most chilling symptom of all has been the current box-office-hit in Tokyo, a thriller called “Rose of the Sea”. The star portrays a Filipina of mixed Chinese parentage who operates as an American spy in Japan, transmitting military information through a radio set hidden in a Christian church. She reforms in the end, of course, arid realizes “her true Asian destiny” but the implications are ominous. The film could not have been produced without official approval; indeed it is said that it was produced under the auspices of the military police. If it was, then the plot provides a good clue as to the No. 1 police suspects in Japan: Filipinos, Chinese, and Christians. It is a far cry from the 1944 box-office sensation, “Shoot Down That Flag” which portrayed the Filipinos in Bataan and Corregidor as oppressed by race-conscious Americans.

One of our students sneaked into a downtown theater to see “Rose of the Sea” the other day. When the lights went on, his neighbor, a Japanese, turned on him suspiciously and asked sharply: “Are you a Filipino?”

He looked so threatening that the poor boy stammered:

“No, Burmese.”

Aftermath

Fr. Juan Labrador, OP, would summarize events in three entries in his diary.

On March 17, 1945 he wrote a detailed description of the ruins of Manila:

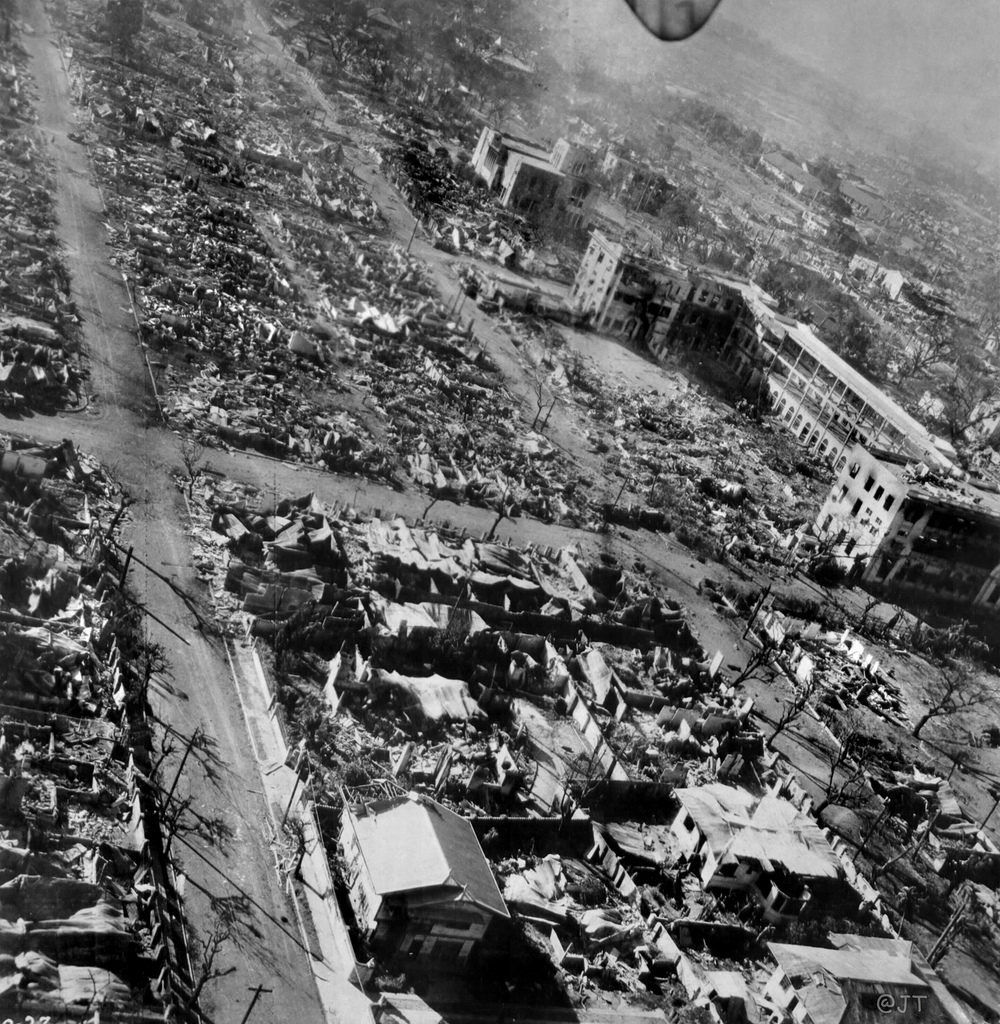

I made a double round of the devastated city. As I viewed the kilometers of ruins and rubble, innumerable mansions, palaces and hotels burned, blown up or razed, holding back my breath every time the stench of corpses became unbearable, my mind was filled with deeply engraved squadron of gloomy silhouettes, sketches of apocalyptic visions, and the chanting of Jeremiac lamentations. It is impossible to transcribe all these on cold mute and blind paper. Neither Poe with his raven, nor Dumas with his dungeons nor Blasco Ibañez with his horsemen, could capture in words this immense picture of desolation. For one who had not seen this, it is impossible to believe or imagine it. And even if believed and imagined, it could not be reproduced. Everyone, soldier or civilian, who has visited this place, repeated the same refrain: “I never could imagine anything like this. It is horrible.”

Let us trace this sorrowful route which I trekked, pointing out to the imagined tourist these fields of solitude and sadness, as if we were viewing a newly excavated Pompeii or some famous Roman ruins.

To the west of the University, along España and P. Noval, three blocks of houses were burning. Scorched doors revealed the frustrated attempt of the arsonists and their plan of total destruction. The Centro Escolar at Azcarraga and its surroundings had been razed.

I passed by Sampaloc where the two churches, convents and hundreds of houses showed marks of the devastating beasts. I crossed a pontoon bridge across the Pasig near the Rotonda. The whole of Pandacan, which before was covered with gas and oil factories, with warehouses and depots, is now a heap of burned steel and wood. I crossed more bridges across esteros. At the left, I could see what used to be the Paco railroad station, the shoe factories of Hike and Esco. The whole place up to La Concordia and to the south, as far as the eyes could see, are all debris. I proceeded through Herran. At one side, Looban, were the properties of Perez Samanillo. At the other side were the factories and offices of the Tabacalera: burned and busted walls. I cruised along Marques de Comillas and San Marcelino: the church and the seminary of St. Vincent, the St. Theresa’s College, the English Club, houses and more houses, walls and roofs as if eaten up by leprosy. We turned along Concepción. The YMCA was levelled. The Sternberg hospital was demolished. City Hall was battered at its rear portion. As we turned into Taft Avenue, we saw the Legislative and Agriculture buildings reduced to rubble. In front were the Philippine Normal School, the Jai Alai, the Casino Español, the Red Cross, the Philippine Columbian Club with their roofs blown off and their windows exuding tears of smoke and carbon. To the right were the University of the Philippines, the Ateneo, the Assumption, St. Paul, the Bureau of Science, all desecrated. In Baclaran, along Harrison, the eyes revolted and the heart broke at the sight of that sorry mess. Changing sceneries, we proceeded to the Boulevard to watch the protruding — not floating — Japanese fleet which was hinged rather than anchored to the Bay. The merchant and war vessels of the invincible Japanese forces, numbering some one hundred, peeped out of the water, some on their aft, others on their fore and others showing only their mast — all in ridiculous postures hardly worthy of sons of the Mikado. They would be there down on their knees for all eternity, as silent but eloquent witnesses, confronted with the desolation of today and the splendour of tomorrow: the desolation caused by the entrails vomited out from their swollen wombs. It was the navy which entrenched themselves behind the buildings and people of Manila, blowing up and burning both as the liberators hunted them and caught up with them. Among the dead and half-buried boats, the liberating vessels scour the bay, by now cleared of enemies, both visible and invisible.