Dr. Mukaibo greets tis — Internment begins at Brent School — Complete disorganization — We walk to Camp John Hay — The food and water shortage — Camp committee appointed — Dysentery makes its appearance — We supply our own food — Japs begin looting in Baguio — Daily rollcalls — Commingling of sexes prohibited — Nagatomi steals ottr cash — Gray succumbs to “water cure” — Chinese internees arrive — food packages — Missionaries released and promptly reinterned — We hear of conditions on the outside.

At 2:00 A.M. (Dec. 28th) Mrs. Warren Garwick, who was acting Manager of the club in the absence of her husband on shore duty with the Navy at Manila, awoke me with, “Mr. Hind, Hayakawa wants the keys to your automobile.” He was a civilian Japanese resident of Baguio, a department store owner, and considered by many to be in the espionage service. He cooperated fully with the invaders from the moment of their arrival at the

mountain city, but was not the Jap of the same name who for months was in charge of our internment camp. From that moment of waking, the lives of all of us were to be regimented for three years, we were to be cut off from all business and social connections with the outside world, we would hear no more American radio programs, see no more newspapers or periodicals, be reduced to the eating of two very limited meals daily, would be guarded by soldiers with guns and bayonets — in short, we might as well have been locked up in jail insofar as personal liberties were concerned.

At about 2:30 we were told to dress quickly and gather on the front porch of the club. This we did, and here we met Major Muso Mukaibo of the Japanese Intelligence Corps who asked us to give details of our citizenship and then informed us that we would be taken to Brent School at once for internment. Dr. Mukaibo, a graduate of Harvard University and a Doctor of Divinity — a protege of the Methodist Episcopal Church — looked anything but a churchman. He was tall for a Japanese, wore the familiar thick-lensed glasses, a small Hitlerish mustache, was clothed in an ill-fitting uniform of sorts with a pair of leggings to set off the ensemble, and carried a vicious looking sword, patterned after those of the Samurai of legend and picture. As he stood there in the dim porch light, backed by soldiers with guns and bayonets, he looked in none too pleasant a mood. Evidently tired from his

long trek up the hills from the lowlands and anxious to get done with the business in hand, he was impatience personified. Did we have any guns on our persons or concealed about the premises? “Ifu you have and do notta giva them up immediatery or ifu do notta obey the orders of Japanese Miritary you wirra (will) be kirrud (killed)!” were his final words. Certainly this was anything but a display of the Christian spirit which he was assumed to have acquired after eight years of study in the United States. No, we had no guns and we understood his warning. The Japs were surprised to find Baguio unarmed. They refused to believe that we had no guns hidden away, and it required some time for them to come to the conclusion that we had none but peaceful intentions

and were willing to submit to internment without opposition. In the meantime my automobile had disappeared. It had the dubious honor to be assigned to Dr. Mukaibo and continued in his service and those of his successors for three years. All private cars and trucks and buses of transportation companies belonging to enemy civilians were likewise commandeered by the Japanese. For months the streets of Baguio were lined with broken-down

vehicles, and any convenient open space became the depository of looted and wrecked cars.

Dreaded internment had come! With an allowance of one small bag each and without any bedding or other conveniences we were hustled into waiting trucks driven by Japanese civilians and taken to Brent School. Upon arrival our meagre luggage was inspected for guns, kodaks, flashlights and such things as knives, scissors and razors. Many were relieved of their safety razors and spare blades! This done, we were led through the school office, along a hallway and up some stairs to rooms already partly filled with internees who had arrived earlier. On the way we saw, through an open door, a half dozen Jap soldiers stretched out on the floor, fast asleep, and near them little mounds of rice — the soldiers’ rations. The place was guarded by civilians drawn from Baguio’s Japanese population, and all inspections were made by them. The office was littered with a host of seized articles, and most of us saw for the first time one Nakamura, a civilian, who, with Mukaibo, was to regulate our daily lives for several months. It was galling enough to be ordered about by Japanese soldiers but to be told what to do by Japanese civilians with whom we had been dealing as artisans or shop keepers was extremely humiliating.

Entering the room assigned to the men, we found twenty fellow-internees, sitting on boxes, lying on the floor or on tables. The room measured about sixteen by twenty feet and was formerly occupied by one of the schoolmasters. It was a cold morning and several were trying to sleep with the scant and inadequate covering of curtains torn from the windows. Others came in after we had found a place to sit and we all awaited the coming of daylight. We discovered that nothing had been provided for our breakfast, but, through the efforts of Alex Kaluzhny of the Pines Hotel, and Paul Trimble of a local coldstores establishment, we were each served a slice of bread, some spiced ham and a small cup of coffee prepared on an electric hot plate belonging to the school. The Japs did not provide meals for several days!

That first Sunday long will be remembered. There seemed to be no plans made other than to intern us. Dour looking guards surrounded the building, which was crowded with refugees, some of whom had come in the previous afternoon. There was no organization but plenty of volunteers were available who set about to get the school kitchen to function, drawing upon school supplies and those donated by brothers-in-misery who had been able to bring food with them. We could look down upon a small open yard in which dozens of automobiles were parked and where new arrivals had their baggage examined. Some of the women and children were walking in the limited space marked off by the patrolling guards, but no sooner did the men slip out to join their families than all hands were ordered to quarters. This was the first intimation we had that “commingling” of the sexes was against the Japanese code, as it applied to internees.

Some tried to sleep that first day, others took their turns at the wash basins on the upper floor, and still others tried their hand at shaving. With all the confusion, uncertainty and conjecture, a buoyant spirit prevailed. The whole affair was pretty much of a lark, for after a week or so we would all be allowed to go home, we thought, and although there could be no golf today, surely the devotees of the sport could have a game over at the club that day week. But we were again becoming hungry — many of us couldn’t recall when the demand for food had been so keen and a second meal much like that at breakfast was served in the afternoon. Bewildered and unhappy children off their food and rest schedules, made their wants known by having a good cry, adding to the bedlam, and through it all the guards paraded the grounds and civilian Japanese, ex-carpenters from the mines, storekeepers and others, gave orders, with not a little show of pleasure. Had they themselves not been interned for seventeen days until released by their invading nationals? Baguio Japanese were interned at Camp John Hay on December 10th and were released by their troops in the evening of the 27th.

From all accounts the native troops who had their internment in hand had not treated them too well. Here was the opportunity for retaliation and they took full advantage of it. With the thought that perhaps the morrow would bring better things we retired that Sunday night on tables, floors and benches, cold, hungry and tired but full of hope and good cheer — the heritage of the white man who, in time of stress and discomfort accepts such a situation with the best of grace.

At noon on Monday we were given orders to congregate in the tennis courts of the school for an announcement, and were ordered to “be quick about it.” No time was lost and we were soon gathered about Mukaibo who had the habit of appearing from apparently nowhere. We were to move from the school to another place. He did not say where. Trucks would carry our heavy baggage, the aged and the infirm. The rest of us would walk. Be ready in fifteen minutes. That was all — no explanations, no details; nothing. Just get ready to walk. He again cautioned us to obey orders closing his remarks with — “You Americans are a merciful people; we Japanese have no mercy.” It seems that it had been announced in Baguio that this march was to take place and it was expected that many curious Filipinos would line the route and witness the workings of the New Order as they applied to interned Americans. Be it said to the everlasting credit of the Filipino that he did not accept the invitation to participate in this Roman holiday. None lined the roads, and the two or three who

crossed our path went quietly about their business.

We were organized into groups and, carrying as much baggage as we could, finally started on a journey which was the conjecture of many to end at the Pines Hotel, the Country Club or Camp John Hay. As we left the school grounds and passed the residence of a wealthy Spaniard we noted the servants at the entrance crying unashamedly over the sight of us representatives of the United States being guarded and driven like cattle along

those very streets that we had built.

When Japanese nationals were interned by us, they were taken to Camp John Hay in trucks. Why were not we Americans given reciprocal treatment? Certainly being herded like cattle was an undignified spectacle, yet our spirits were high. “We’d be damned if we’d show the white feather.” The women and children we, of course, felt sorry for. It was warm at this hour, all of us were weak from hunger, those bags were heavy, the blankets and other bedding were bulky and difficult to keep under control, yet these three hundred men, women and children trudged along uncomplainingly, stopped for breathing spells at the top of each rise in the road to allow the laggards to catch up with the main groups and to shift bundles to easier carrying positions. The children thought it was a lark, but many of the women were near collapse at the end of the two-mile trek. We were taken past the

scene of the Japanese bombings of the laborers’ quarters near the Baguio power house a few days before and into the grounds of Camp John Hay, through groves of pine trees, past the Administration buildings and in the direction of the newly erected residence of the U. S. High Commissioner.

It is said that if one puts one foot ahead of the other one will ultimately arrive at one’s destination. Most of us did just that under the guidance of armed Jap guards. We finally stopped at the barracks — four buildings, all practically alike — facing a parade ground on the opposite side of which was a group of officers’ residences. One corner of the second building was badly smashed by the bombing of the morning of the 8th and one of the residences across the way was completely gutted. There were several small bomb craters on the parade ground. The trucks with those passengers who could not make the trip afoot followed us and after they had been unloaded of passengers and baggage we were assembled in No. 1 Barracks where Mukaibo gave us another talk, the last that we were to have the dubious pleasure of hearing. He told us that the women and children would occupy the north half of the building and the men the south, that there must be no commingling, etc.

In the meantime, Jap civilian carpenters were erecting a wooden railing dividing the quarters in two. There was a feeble trickle of water in the taps, which was mighty welcome after the hike from Brent School. However, no provision had been made to feed us and a supper of sorts, — crackers, canned meat and coffee — was provided by volunteers. All hands “turned to” to get ready for the night. Some lucky ones had brought mattresses with them but the majority of us slept on the bare floor. There were no lights, for not until the next day was the electric current switched on.

We were occupying the same building in which the Japanese were interned, and it was plain that we were not to be any better treated than they had been. For three days, it is said, they were practically without food or water, due to the carelessness or indifference of the native constabulary who had the internment job in hand, much to the irritation of the Japs who lost no time in impressing upon us that sauce for the goose is sauce for the gander.

Tuesday and Wednesday were awful days. Our water supply gave out completely. The water system was interconnected with that of the High Commissioner s home, where the Japanese commandant for the Baguio area had taken residence, and not only were there innumerable valves to be manipulated but certain reservoirs had to be filled before others could receive water, and we were tied in with the second lot of cisterns. The commandant demanded that his residence be supplied with water before we were served. Also, the pumping plant would not function. We leave to the imagination of the reader how nearly four hundred souls fared without an adequate water supply. Drinking water was brought in from elsewhere on the reservation by our own men, and each person was allowed a cupful twice daily. New internees were arriving hourly, adding to the discomfort and confusion. On one point we had no complaint — the camp kitchen was adequately supplied with utensils, good stoves, an abundance of crockery and silverware, left behind when the garrison of Philippine Scouts took to the mountains before the Japs arrived. Some of us had brought in small quantities of food supplies which were pooled and stored in a community storeroom. The meals on these days were little better than makeshifts and certainly wholly inadequate for the maintenance of health or strength. The nights were made hideous by the foot-dragging of Jap soldiers tramping through the barracks. Anyone who has been in Japan remembers the dragging, clop-clop of wooden shoes or “geta” on the sidewalks. Shoe these people in leather boots and leggings and the habits of a thousand generations manifest themselves. The Jap soldier is the world’s best foot-dragger — there can be no better!

On the last day of the month — and of an eventful year — the water shortage continued but a semblance of order was slowly manifesting itself. A committee was appointed, chiefly from those men who had displayed public spirit and a willingness to serve. Elmer Herold was appointed liaison officer to cooperate with the Japanese authorities. Mrs. Herold and a group of aides took the women’s problems in hand, a dispensary was set up at the south end of the barracks and a cook’s crew was organized with Messrs. Kaluzhny and Trimble in command. Rice was supplied by the Japanese but we had to furnish the rest of our food. It was during the first trying week that much weight was lost by nearly everyone. There was plenty of canned milk for the children, and from the first day the little tots were well provided for.

No one saw the Old Year out. We were too tired, too hungry and too dispirited. Such things “couldn’t happen to us” but they had. We had ceased to be individuals in the broader sense — we were a lot of helpless sheep snatched from our individual way of life, thrown together, friend and stranger alike, into a pool of inaction and frustration and undergoing a process of regimentation under the Japs who were now our enemies. We knew now, what it was to be interned, and with heavy hearts we passed from the old year into the new.

— January, 1942 —

There were no egg-nogs nor mint juleps served on New Year’s Day, and none of the usual happy gatherings and ‘open houses” so familiar to residents in the Orient. Instead, we had water and plenty of it for this precious fluid was back in the pipes, thanks to the efforts of one of our number who undertook to repair the pumps, and shower baths, the washing of clothes and copious drinking of water were the order of the day. It was on this day

that three cases of dysentery appeared. This disease was a scourge throughout our internment, although injections against dysentery, typhoid and cholera were given to practically everybody at regular intervals.

During the first week food was very scarce, its daily caloric value being about 600 per capita although in the Baguio climate at this season of the year about 2500 calories are required to maintain one’s health and strength. Vegetables made their appearance on the 3rd, and thence forward we were able to allay hunger at least once daily, at the second and final meal of the day in the late afternoon. The Japs furnished rice and sugar but we were obliged to purchase with our own funds, all other food — meat, vegetables, fruit, etc., augmented by the stocks on hand of coffee, fats, condiments, tea, milk and a limited quantity of canned goods. To this end the adults were called upon to subscribe a fixed amount weekly. During the first three weeks a total of 3.50 pesos was collected

per capita which was increased to 1.50 pesos a week thereafter. A light station wagon had been supplied us (looted from one of the mines, of course) and with two or three cooks aboard it made daily trips to market for meat and vegetables.

Reports of looting by the Japs, and in some cases by the natives, began to be heard as the final groups of internees arrived. Homes were stripped of their contents. Stamp collections, rare books and other property, personally prized and irreplaceable, were carried off. What was of no value to the looter was destroyed. Such tragedies, however, were not without their humourous side. The home of a prominent Manilan was to be put through the paces of organized looting and one of our number was sent for to open the residence and unlock cupboards, trunks, etc., for which he held the keys. The Japs discovered some pianola records. “Aha, here was something. What are these round holes and slots in these rolls of paper? A private code?” When assured they were of no value to the Intelligence branch of the army the looters took great delight in unrolling the reels across the spacious drawing room floor.

On the 3rd all safety deposit box keys were called for by the authorities. The only boxes in Baguio were in the Peoples Bank branch, and W. M. Moore, the manager, and a fellow-internee, was ordered to go to the offices and facilitate the looting. It is difficult to estimate the value of the plunder garnered in this operation but it must have run into hundreds of thousands of pesos, to say nothing of the loss of stock certificates, insurance policies, wills and the dozen and one papers that have no worth to a looter but are only replaceable, if at all, with great difficulty.

After a week in the barracks along with the women and children, and suffering all manner of inconveniences in common with them, we men were ordered to move next door to Barracks No. 2. This relieved the congestion and ended the embarrassment of having to dress, undress and perform one’s toilette more or less under the feet of the opposite sex. It was at this time that we had our first line-up on the tennis courts for identification and classification, and the morning roll-call before breakfast was a regular chore for several months.

For some unaccountable reason, the Japanese, from the first day of our internment, forbade commingling of the sexes even during daylight hours. That we should be separated at night is understandable but why wives and husbands might not sit down for a chat in public has always been an unanswered question. There were two tennis courts on the grounds a few yards from the east end of Barracks No. 1. One of these was assigned to the

women, the other to the men. Parallel lines were painted on the floor of the courts about eight feet apart between which traffic was taboo. It was amusing to watch couples trying to converse about family affairs across this neutral zone. On Sunday evenings, from six to seven o’clock we could join our families and parade around both courts — Herold s whistle indicating the beginning and the end of the ”commingling period.” If there was any serious infraction of rules during the week, this Sunday privilege was often denied us. All this was not in the nature of a hardship, but it was one of those things that made internment all the more difficult to undergo. It had nothing but a nuisance value and restrictions on smoking, which were later imposed upon us, only served to embitter us. We were not military prisoners, we were civilians and ought to have come under a somewhat different category in the matter of treatment.

The 10th of January will not soon be forgotten. Late in the morning it was announced that all our money would be taken from us by the Japanese. We resignedly assumed that it would be done by the army. Much to our surprise H. A. Nagatomi, a Jap contractor of many years’ residence in Baguio, and a Rotarian, arrived with some fellow civilians to do systematic looting of our purses. The barracks was bisected by a passage, about fifteen feet wide, which led from the front steps and porch to an enclosed verandah in the rear which, in turn, connected with the mess hall and kitchen in another building. Without much ado it was decided to take the money from the men in the north half, first, and all occupants of the south half of the building were ordered to the tennis courts to await their turn. We, the first victims, were told to stand by our allotted sleeping space. A table and a couple of chairs were placed in the passageway. Nagatomi and a clerk seated themselves at the table and it was announced that we would each be allowed to retain 100 pesos but that all sums above this amount were to be turned in, for which a receipt would be issued and at a later date the money would be returned. It never was.

One by one we were questioned, and our baggage thoroughly gone over. In many cases the mattresses were given a thumping, in the hope that hidden funds might be located. Stock certificates, life insurance papers, cheques, etc., were taken up and each of us was obliged to go to the table when cash was counted. All but a

hundred pesos was placed in an envelope upon which the victim was told to write his name.

The examination completed, we were herded onto the tennis courts and the “south-siders” were called in. Many who had gone through inspection were able to take purses and valuable papers from those who were on their way to the fleecing. When the men had been attended to, the women’s quarters were visited by the Nipponese bandits. Wives, with husbands in camp, were obliged to give up all their money. Unattached ladies were allowed to retain 100 pesos. There have been many estimates of the total amount of which we were robbed, a conservative guess being 5200 pesos. There is no doubt that Japanese civilians held us up but it is inconceivable that the military did not have full knowledge of the robbing, else why were armed guards posted within the building?

It was reported that missionaries were not interned at Santo Tomas in Manila — the largest camp in the Islands where nearly 4000 people were under “protective custody.” The greatest number in our camp at any time was about 500. This led us to believe that the first to be released would be members of the cloth. During the third week of the month, five missionaries were taken each morning to Intelligence headquarters for questioning upon the return of the station wagon with food from the market. One day three of the five men failed to return in the afternoon — R. F. Gray, R. C. Flory, and H. G. Loddigs. Flory and Loddigs were kept in jail for several days and later returned. Gray died on March 15 th, we learned several months later, from the effects of the “water cure” — a means of forcing the truth out of a person praaiced for hundreds of years upon prisoners by conquering armies and brought to the attention of the present age during the Spanish-American war. Until we were advised of Gray s death the Japs told us that, though imprisoned, he was being considerately treated. In administering the water cure the victim is seated in an ordinary chair, his lower limbs are strapped to the chair-legs and his body and arms pinioned to the chair-back. The chair is then tipped back to rest on the floor just as an overturned chair usually lies, the trunk and lower limbs of the poor man being now parallel with, and his thighs at right angles to, the floor. The principal in this setting is then given water to drink — more water and then more water. Nausea ensues. Then the nerves causing stomach convulsions become deadened and a distention of the abdomen results, bringing with it untold agony, aggravated by having an inquisitor jump on his belly. It is then that the

victim “talks” — whether he tells the truth is of little consequence so long as he gives information to his questioners. It was rupture of the intestines that caused Gray s death at the Notre Dame Hospital, where he was taken, unconscious and dying. There have been many conjectures as to why Gray was subjected to such cruel

treatment; none, in our opinion, meriting the water cure. Perhaps he was indiscreet; perhaps he was a pacifist; perhaps he had been too friendly with the Chinese (he was connected with a Chinese language school in Baguio) — certainly he was not a spy in the accepted sense. He had been interned and was entitled to the protection of the Japanese.

On the afternoon of the 8th the first contingent of 462 Chinese internees arrived and were assigned to Barracks No. 3. As Baguio’s pre-war Chinese population was well over 2000, it is assumed that many took to the hills or rushed to Manila before the Japs took control. Upon arrival, all bundles and other baggage were examined on the parade ground for contraband, during which a shower of rain fell, dampening everything and resulting in an

unpleasant night for all hands but this did not concern the Japs. A few days after they were interned, prominent members of the little community were taken in groups of two or three to Intelligence headquarters, along with the daily contingent of missionaries, and grilled on several subjects, chief among which was the location of hidden or buried treasure, for it was known that prior to occupation by the Japs the Chinese took all possible safeguards to protect their personal property.

Leung Nang, Baguio’s most prominent Chinaman (a fellow Rotarian of Nagatomi’s) , was among the first to undergo questioning. I saw him leave camp one morning. He looked very miserable and apprehensive, and when he returned it was plain that he had been through hell. His face was swollen and he walked like a man who had been under the lash and seriously hurt. It was not until early March that he told us about the treatment he had

undergone. He had been given the “water cure,” had had 15,700 pesos taken from him and his grocery store was robbed of all stocks and fixtures. Leung is a mild-mannered fellow, well educated in the use of English, and the head of a large family, to which he was singularly devoted. After his terrible experience, I saw him many times in the barracks across the way from us and he always greeted me with a nod and a smile. One would never have known that all he possessed had been taken from him nor that he had been terribly manhandled.

No subject was of greater interest during this and subsequent months than was that of incoming “packages.” It meant food for those of us lucky enough to have thoughtful friends on the outside who, for one reason or another, had not been interned and for those who had native families, for unless the Filipino wives of those in camp expressed a desire to join their husbands they were permitted to remain at home. In the beginning, messengers brought the food packages in. Later, they were not allowed to deliver them but were ordered by the guards to return home. It was pathetic to see a native arrive with a hamper only to be told that not only could he not talk to his master but he must take the food back with him. Such an order on the part of the Japs is understandable. Information as to the progress of the war must be withheld from us at all costs. Later, packages came in by the food truck- — but when notes were found secreted in the packages, the order of “No More Packages” followed. This would stand for a few days and the regulations would then be relaxed only to be enforced again when another violation occurred.

There was great excitement in camp on the 30th. It was announced that all missionaries and their families would be released. There was a hum of preparation and packing in both men’s and women’s barracks, farewells were said and at five in the afternoon the happy group, 160 strong, was piled into waiting trucks along with bags, mattresses, blankets and odds and ends of every sort. Their being released raised the hopes of the rest of us

that soon we too would be turned loose, and with cries of “We’ll see you soon,” we turned to the chore of arranging our sleeping spaces, for such an exodus of people, more than a third of our number, eased the congestion appreciably. Much to our surprise 157 of the missionaries returned the next afternoon. A sad and

chastened lot they were; they no longer bore the happy faces with which they had said farewells not twenty-four hours before. Then came the unpleasant job of bringing in the baggage, rearranging bed space and going through all the motions that would have been necessary had an equal number of new internees arrived. They

were famished, for many of them had had no food since leaving. They had been trundled off to one of the local hotels and one by one told to go to their homes, apartments or wherever they had their abode. Then it was decided by some one in authority that only those would be released who had bona fide residence and duties in Baguio. Most of the missionaries were refugees from China and had no mission work in Baguio although many of them were connected with the Chinese Language School operated by several denominations, jointly, for the teaching of that language. The existence of this school was anathema to the Japanese and many connected with it were subjected to severe questioning and indignities. This was the last mass evacuation, albeit a false one. Thereafter releases were seldom made, and then only a few at a time. Intelligence headquarters became better organized and much red tape had to be gone through before protective freedom became a reality for the fortunate ones.

During this month much was done to ameliorate an unhappy existence. The men played bridge, poker and cribbage, a camp newspaper was started, tennis and volley ball games got under way and organized games for the children became a part of their daily life. Singapore and Bataan had not fallen and they were not expected to fall. Our release was only a matter of days or weeks. We never dreamed that it would be years before freedom would come.

It was impossible, we thought, for the Philippines to be completely occupied by the enemy. We heard all manner of stories of relief and reinforcements being on the way, units of our fleet were in Philippine waters, troops had landed here, there and elsewhere, and from day to day we were told by the supposedly informed among us that “things were going well,” the guerrillas were within a few miles of Baguio, etc. In January we expected to win the local war because we were foolish enough to believe that only time enough to move ships across the Pacific was needed to stop the Japanese advance, and when fewer and fewer automobiles were seen on John Hay roads, and Japanese planes no longer flew overhead, we took the first fact to be an indication of a shortage of gasoline, and the second evidence of fighting plane reinforcements from the States. We lived in the clouds during this month of internment.

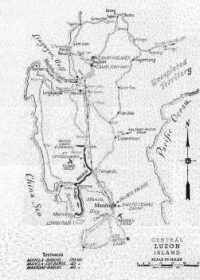

The first disturbing report of conditions in the lowlands was brought by Helge Janson, Acting Swedish Consul, who came to camp to take Mrs. Janson and their two children to Manila, for, under diplomatic immunity, Consuls’ families may not be interned. This was on the 11th. It required nine hours to make the trip which is normally negotiated in four. He was under guard and was no doubt instructed not to talk but what little he did say was

dampening to our spirits. The Luzon plain, he reported, was desolate and the roads lined with dead soldiers and animals. Further, matters were not going too well with us. This was the first intimation that we had that the Japs were gaining the upper hand, and it began to dawn upon us that our release was a matter not of days nor of weeks but probably of many months.