Shortage of salt — Bataan falls — Easter celebrated — More Chinese arrive — The tobacco crisis — We are transferred to Camp Holmes — Getting settled.

The warm days and cool nights at Baguio s mile-high elevation brought colds and bronchial troubles to many, which, in some cases, developed into pneumonia although, happily, there were no deaths from this disease. All of us continued to lose weight but some reached the point where the food intake was sufficient to check weight declines. We suffered temporary shortages of one thing or another — salt being one commodity that was absent from the tables for a few meals, coffee was beginning to show signs of running out and when laundry soap became scarce one of the internees made some with lye and rendered lard but it was soon discovered that the latter was more valuable to the cook’s department than as a soap ingredient and the camp soap factory closed down.

Great was our disappointment when it was definitely learned that Russia was not at war with Japan. The defense of Bataan was reported to be going splendidly, however; our troops were being landed on the island of Cebu and statements such as “The news is good,” coming in notes concealed in food packages, bolstered our morale. Then, just as our hopes had once before been dashed by the fall of Singapore, we awoke on the morning of the 10th to find this notice tacked up in front of our barracks where all could see:

Bataan Fell!

finally with

Unconditional Surrender

April 9—7 P.M.

Now let us realize

“The Orient for the Orientals”

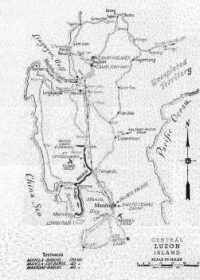

Our men had held out for four months under terrible conditions. Ill-equipped and untrained men, without outside help, had fallen back from Lingayen Gulf, across the plains of Luzon to the southernmost tip of the Bataan Peninsula. They had suffered sorely, malaria had gotten in its deadly work, food and ammunition had given out and General Jonathan Wainwright was finally forced to capitulate because it was impossible to fight on. All these

circumstances were extenuating and unavoidable but one bare fact predominated — the Philippines could not be defended. The problem now was how to win the Islands back — and when. The Japs may not be invincible but they had shown extraordinary fortitude and disregard of life. The Philippines were theirs in the meantime. Singapore’s loss had been a blow but that was British territory, and now Uncle Sam had tasted defeat. We did not learn until later that the brave stand at Bataan had made Australia’s capture by the Japs impossible, but the immediate effect of this calamitous news was to bring our spirits to the lowest ebb. It was not easy to face our Jap captors with the props knocked from under us, but in time our spirits revived and the sting of defeat

grew less as reassuring news — this time authentic — that the ultimate aims of the war that had been imposed on us by a treacherous enemy would be attained in spite of anything that might transpire. This was a war of material and air power. Well, we were second to none in industry, and the airplane was our child.

Our Easter season was a memorable one. On Good Friday we were served a hot cross bun of sorts, which did not measure up to the article served in our homes under happier circumstances because of the use of flour substitutes and the absence of some necessary ingredients, but it was a brave attempt to meet the demands of tradition. Easter Sunday was ushered in by an early morning service on the tennis courts. Climatically, Easter in the Philippines is usually a grand day. It comes in the dry season and at a time of cloudless skies. This Easter was no exception, and the altitude of Baguio gave the air a crispness that is always associated with spring at home. We may have been under the control of Jap guards whose flag flew atop a pole only a few yards away but our

spirits were good and our thoughts were turned to our homeland and those members of our families who, fortunately, were not with us. There were many women refugees present from Hongkong and Shanghai who had heard nothing from their husbands since the war began, and there were many American women whose husbands were engaged in the defense of Bataan. What a brave lot they were!

On the 11th the Chinese whose homes were in Manila but who happened to be in Baguio when the internment dragnet swept them into concentration camp, were released. No Chinese was interned at the Capital City except a few who served as hostages. Eight new Chinese internees were brought in, however, as the others were released. These, with four others, had been in hiding in the mountains near Baguio when found by a Japanese patrol. Upon offering resistance to capture, two were killed and a third wounded in the foot. The command of the patrol ordered this unfortunate shot. One soldier refused to do it but a willing hand was soon found to dispatch the Chinese. It was “too much trouble” to bring a wounded man to headquarters in Baguio! A fourth Chinaman hid in the rafters of the shack they were occupying, but as the house was afterwards burned by the Japs the fate of the poor fellow is not known.

The pinch of high commodity prices began to be felt during the month. A popular brand of American pipe tobacco which in normal times sold for a peso (50 cents, U. S.) a pound was selling for 8.00 pesos. American cigarettes were 2.00 pesos a package. Even native cigarettes were four times normal prices; evaporated milk formerly at 18 centavos per can, rose to 65 and 70 centavos; flour sold for 9.50 pesos the sack ($19.00, U. S. per

barrel); and locally produced sugar rose to three times normal prices. It was later explained that surplus sugar stocks were converted to alcohol motor fuel for Japanese military use, hence the price rise. Pipe smokers, unable or unwilling to pay market prices for imported tobaccos, tried their hand at curing their own by buying leaf tobacco for 65 centavos a “hand” of 100 leaves and experimenting with every conceivable method of curing and preparation for the pipe bowl. All experimenters washed the leaves, for, unwashed, the nicotine content was too high, but how long to wash it and whether or not to add anything to the wash water were disputed points. Some recommended sugar, others maintained that salt water was preferable. When the leaves were dried and the stems removed, for the latter are as bitter as gall when burned in a pipe, they were cut into the familiar form known to all smokers. Here the experimenting continued. Licorice essence was added or sugar syrup, in the absence of molasses, and then the final produa was set aside to “age.”

While at four o’clock dinner on the 20th there was great excitement when it was announced that we were to be moved to Camp Holmes, Trinidad Valley, on the 23rd. Trinidad was the vegetable center of Baguio, being farmed mainly by Japanese. In this valley was located the Trinidad Farm School where 650 Filipino students were given an academic and agricultural training under American supervision. Less than a mile away was Camp Holmes, headquarters of the local detachment of the Philippine Constabulary or Insular Police and used as a training center for the Philippine army.

The next morning a crew of fifty of our men, including fifteen Chinese who were to prepare quarters for their own nationals, were transported by truck to Holmes armed with all manner of tools, including the complete equipment associated with a modern janitor service. Included were some of the kitchen crew who were to enquire into the needs of this important department and to lay the groundwork for our reception and feeding when the general

exodus from Camp John Hay took place.

After a six o’clock breakfast on the morning of the 23rd, married men were permitted to go to the women’s barracks to assist in the final packing. What a mad-house it was! Hammering of nails, moving baggage out of the building, howling children or children so excited over the prospect of moving that they were entirely immanagable, and unattached women yelling for someone to come to their aid in rolling up mattresses and blankets or in closing bags which were packed to the bursting point. Everyone was in a holiday mood and the transfer took place under circumstances reminding one of an excursion. For better or for worse, it was a break in routine and we were off to the other side of the mountain “to see what we could see.” Some of us, the writer

among them, had not been outside the fenced enclosure since coming to Camp Hay. Our movements had been limited to a 250-foot concrete walk in front of the two barracks and the area of one of the two tennis courts.

There were three barracks at Camp Holmes, all facing west. The North building, an old one-story affair built in 1927, was assigned to the men. The center and south buildings were new, having been erected shortly before the war. These were two-storied buildings, equipped with self-contained kitchens and mess-halls. The middle building was assigned to the women and its duplicate to the Chinese. A spacious parade ground lay in front of the buildings, at the opposite end of which were the work-shop and the guardhouse. To the left and south was a series of hills less than a thousand feet high heavily wooded with pine trees —the common trees in Baguio. At the right of the compound the land gave way sharply to a level piece of ground on which were tennis courts and two officers’ residences, the larger becoming our hospital and the other a nursery for camp-born children. Round and about stretched attractive roadways with rock gardens and flower beds and vine bedecked trellises to add to the beauty of the spot.

The view to the northwest was down the San Juan valley to the sea where is located the town of San Juan in La Union Province. (It was here that the Japanese gave first evidence of their murderous cruelty as they marched south, Manila-wards, along the coast from Vigan for the entire populace, except those who escaped, was killed — in many cases women and children being bayonetted. ) On clear days the China Sea was visible. Then to the northeast lay some of the most beautiful scenery in the Baguio area — tier on tier of mountains rising into the Mountain Province country where General Tomoyuki Yamashita was finally cornered three years later. At one’s feet were small cultivated areas with the farmers’ huts nearby and in the middle distance terraced rice fields. We were quick to agree that our new location was preferable to the old. We had ten times the area to wander around in, we had a superb view and we had better living accommodations.

After a late supper of stew and boiled rice we were off to bed. The Japs insisted that lights remain switched on all night but this did not affect our ability to drop off to sound sleep at once for our stamina was not what it used to be. After a breakfast at eleven the next morning, the task of getting settled was undertaken. This required a couple of days hard work, saws and hammers being busy with shelving and other conveniences. Everybody wanted his job done first and barracks floors were strewn with everything from handbags to umbrellas and bawling children were under foot. We had been at Camp John Hay 116 days. How long would we be at Holmes?