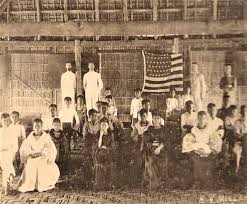

THE SCHOOL AT JANIUAY

The next morning after my arrival in Janiuay, the four native teachers — two men and two women — came up to call on me and we hed a long interview, McC–~– acting as interpreter. I told them that according to instructions given me by my superiors, my status in the Janiuay school is that of a teacher of English and nothing more. To this, the native principal demurred saying that it was his wish that I take general charge of all the school activities. (As a matter of fact, that is just about what I am doing, although without any ostentation.) After our interview, I went with the teachers to the school and “observed” a class of boys recite in Baldwin’s First Reader. (The military authorities brought a lot of English text-books into the Islands and distributed them around among the various schools, often, too detailing an enlisted man to act as teacher.) I also spent the afternoon observing the work of the different classes and that evening I gave my first lesson to the teachers. Both the teachers and the pupils seem eager to learn end they deserve great credit for what they have already accomplished. But they lack familiarity with English, and the school-room methods and devices are at least medieval.

The boys and girls are assembled in separate buildings. (This is not a bad plan, and I mention the fact here merely for the sake of information). In the boys’ building, the teacher’s table is in the center of the one large room; and there is one blackboard about three by four feet and one piece of of crayon. Although there are two teachers in the building, there is no partition between their classes. Most of the boys are seated along the side and end walls of the building upon long running benches made of three or four bamboo poles pinned together and supported upon stakes of the same material set into the earth below the floor. These benches are the same height all the way around the room and they have no backs; so. that not only do the feet of the smallest boys come away above the floor, but none of the boys have anything to lean against excepting the damp and even slimy stone walls of the building.

The floor is made of bamboo strips woven together and supported upon bamboo stringers. It gives down under foot and rises fore and aft as one walks across it, like the rise and fall in wave action. Between this floor and the ground, there is an unventilated space of about a foot, which serves as a rendezvous for divers and sundry beasts and creeping things. Several times I have seen rats as large as half-grown cats emerge from below this floor, look about for a moment, and then suddenly scutter back into their nether regions. Then, too, many of the boys chew betel-nut and expectorate through the cracks in the floor. The saliva decaying in the dank tropic heat, togethher with various other kinds of putrescent matter, gives rise to a stench which his simply appalling.

The girls’ building is not so bad. It has a floor of broad hard-wood boards with very little space between them and

the earth. Only a few seats of any kind are provided in this building; consequently, most of the girls sit upon the floor. However, this does not cause them any inconvenience, for they are accustomed to sit upon the floor at home.

The very young girls are generally clothed in single garment — s sort of camisola. The older ones wear the standard garb of the Visayan women — the chemise, the patadion, the shirt-waist or camisa, end the paño. The chemise is made of muslin, cut low in the neck, end gathered. The patadion is invariably made of a red-and-white or blue-and -white checked cotton material. Imagine a wide sack; cut off the bottom of the sack so that it is fully as open at that end as at the top. That is the manner of the patadion. The woman steps into the affalr, pulls it up until the top resches her waist line (the natural waist line), gathers it tight about her waist, and tucks a portion of the gathered part under another portion of itself in a manner that defies description. It stays for a while, and then it is gathered and tucked in again. I take it that the patadion is about the same as the sarong of the Malay Peninsula and the Dutch East Indies. No heagear and no stockings are worn. The feet are protected by chinelas, or “mules,” whick klip-klop along, or drag, according as the wearer raises her feet or no.

Among the Visayan women, it seems that well-to-doness is indicated by the number of patadions a woman wears at one time, especially when attending mass or some social function. Sunday morning, I watched an elderly woman ford the river on her way home from church. She caught up the skirts of eight patadions to keep them from getting wet. The ninth one she left down to conceal her limbs. Then she reached the far side of the river, she released the ninth one (which by that time was thoroughly wet) without disengaging any of the eight dry ones above it, wrung it out, threw it across her arm, and.went on her way.

The camisa is a flimsy peekaboo affair, the principal feature of which is its very wide sleeves. It has no belt and considerable attempt is made to fit it snugly about the waist. The paño is a large square piece of cloth of the same material as the camisa, commonly of home-woven sinamay (banana fiber) or, but less frequently, of it piña (pine-apple fiber), It is folded diagonally, and then folded back once or twice parallel to the first diagonal line. This is worn about the neck with the points fastened together with a brooch, or an ordinary pin.

The boys’ attire consists of a pair of cotton trousers and a shirt, the tails of which are worn outside the pantaloons. A few of the boys have undershirts. The shirts are usually made of the coarse stiff sinamay fiber; and when a boy has sat through a session of school, the tails of this garment are so wrinkled and twisted that he presents a truly comical appearance.

The school room methods inherited by the Filipino teachers from the Spaniards are not much to speak of. In the recitation, absolutely no attention is paid to whether or not the child understands his lesson. He is judged upon the basis of whether or not he is able to repeat the exact words of the text-book. I have seen forty children standing in a circle around a teacher, each one in turn being required to repeat what he had conned over in the book. While one was “reciting,” the others paid not the slightest attention to him or to the teacher (nor were they required or even expected to do so) but spent the time talking and laughing or amusing themselves in any manner they pleased. But woe unto the youngster who fails on two or three successive efforts to repeat his lesson letter-perfect. The teacher has very definite notions of what constitutes a “lack of understanding” and is not averse to applying the remedy suggested in the letter half of Proverbs 10:13.

The study period is nothing short of extremely amusing. The pupils study (?) aloud, conning the text-book in a never-varying monotone producing an effect much like in the case of the pupils of Ichabod Crane. The hum of a Filipino school would enable one to perceive its existence and approximate whereabouts while yet a long way off. When this droning becomes so strong (it gathers strength as it goes along as a machine gathers momentum until it reaches its customary working speed) that the teacher can no longer make his voice heard above the din, he strikes the table sharply with a pliant rattan cane two or three times and says “s-s-s-t” as loud as he can, like a belt slipping under too much power. At this the pupils. quiet down for a little while; but they are soon going it again as strong as before, whereupon the performance of restoring order is repeated. As so on, all day long. while this conning process is going on, the pupils hold their books only a few inches away from their eyes and in an upright position and at such a level that their faces are quite hidden.

It seems that in Spanish times in the Philippines, the public school was little more than a vestibule to the church. There wore no free schools above the primary grades, and the instruction given in these grades was confined within very narrow limits. It consisted chiefly in learning by rote, first in the native dialect and later in Spanish, the elements of the Christian doctrine, the catechism, and a number of other very elementary matters more or less closely related to those just mentioned. Later on, some such text-book as “El Monitor,” or “Manual de la Infancia” was given the child. The content of these books wss almost invariably far beyond the pupils’ comprehension. I have found a number of these books here, and although I know only a few words of Spanish, still with a fair knowledge of Latin I have been able to make out something of the subject-matter. There are a few pages on the essentials of the Bible; a few more on moral philosophy; and perhaps a short treatise on urbanity. The remainder of the book, which contains some two hundred pages in all, is about equally divided among arithmetic, grammar, geography, orthography, geometry, and even astronomy! Naturally only a very small portion of such a book could ever be mastered by a child in all primary school; and naturally, too, only a very small percentage of the Filipinos ever came to know more than a very little about the Spanish tongue. Possibly that was not one of the aims of the educational system of that time. One can readily believe that it was not, especially in the free primary schools. I am told that as a general rule, only those Filipinos came to know Spanish who attended the seminaries and other higher institutions of learning in Manila and a few other places. These were all revenue-producing schools!

Mention may be made here of another custom that is almost amusing. Whenever the native principal, or myself, or any other person of more than average authority enters the school room, every boy stands up, strokes his hair back pompadour fashion with the palm of his hand and shouts the “time of day” at a pitch pretty close to the top of his voice.

In Spenish times, the schools were equipped with furniture of a rather medieval style. A few of the desks called pupitres are still here. They are long enough to accommodate four children and the backless seat is ingeniously attached to the desk in front instead of to the one behind. The affair has a slant top, the top really consisting of a series of hinged lids, so that by raising the lid the pupil may deposit his books in a boxed~in portion below. The seat boards are narrow — from six to eight inches in width — and the pupil in leaning back may support his body against the pupitre behind him, if perchance there be one near enough. I can not think of anything that could possibly be designed upon more unhygienic principles than this piece of furniture. Presumably, and fortunately, the great majority of these desks were carried away and used for lumber or firewood during the recent insurrection.

I can see now that the first and most obvious difficulty which will have to be met is that of the extremely unsanitary condition of the interior of the school buildings. As already indicated, where a building has a floor the result is worse than if there were no floor at all. Then, too the lighting is wholly insufficient and during the rainy season the interior surface of the walls is continually wet and slimy and even grown over with lichens in large patches.

Another great difficulty is that of how to create a competent force of native assistants. As already pointed out, the methods used by the Filipino teachers here are almost absolutely worthless, if not worse than worthless; and none of them have any knowledge of English. Verily, it is going to take time and lots of it. The outlook is not at all hopeful. Dog-fight!