New camp committee elected — Nakamura takes charge — We report our cash holdings to the ]aps — Rice becomes our main diet — Singapore falls — Japs raise their flag over Camp — Camp schools open but soon close.

While assembled at Brent School, a general conmiittee was named to represent the groups there which, during the first month at Camp John Hay, did yeoman service in organizing camp life. A special election was held this month for the naming of a new committee and with more or less regularity during the entire period of our internment elections were held and changes made in committee personnel. Direct contaa of individuals with the

Japanese was not permitted. This was a funaion of the committee chairman or of the committee itself but their path was not rosy as will be seen later in this chronicle.

Many rulings of the committee were made under pressure of Nakamura, our first civilian Japanese Camp Commandant, who, through the period of his captaincy, made life as unpleasant for us as possible. This Jap was a carpenter and from all reports a good one, but he had worked so long under American miners that when the opportunity came to assume authority over them and other enemy nationals he did so with a will to the accompaniment of much foul language. By this he expected to overcome his inferiority complex, for, after all, he was nothing more than a Japanese peasant. It was he who was opposed to the commingling of the sexes, the holding of religious services, entertainment in any form, smoking, except under rigid rules, and who seemed never to realize that we were civilian and not military prisoners. Not only was smoking limited to defined areas but ashes and burnt matches must not be dropped willy-nilly. Instead, every smoker was obliged to carry an empty can to serve as an ash receptacle.

The committee was asked on the 4th to report the amount of money held by us and this was recorded to the colleaive total of 5500 pesos ($2750) which was turned over to the joint custody of the committee and Nakamura. A looted safe was repaired and the money deposited therein. Each morning, before the food truck left for market, the daily allowance was meted out to our buyer — Nakamura, himself. We thus continued to buy our own food with our own money through the agency of a Jap, yet we were supposed to be interned at the expense of the enemy.

On the 4th several of us bottonholed the chef and suggested that in addition to a breakfast of boiled rice that cereal be served at the late afternoon meal for no starches were being supplied such as bread or white potatoes. He agreed to give it a trial, which proved so popular that a “side dish of rice” appeared on the daily menu thenceforth. Little did we realize that before the end of our internment we would be eating almost nothing but rice!

We had expected the occupation of Manila in early January, because it had been declared an open city and therefore without defenses, and when the Japs disregarded the declaration and bombed the city we were resigned to its ultimate fate as our forces prepared to take a stand on the Bataan peninsula and the fortified island of Corregidor. We were unprepared, however, to read hurriedly scrawled signs attached to nearby trees at both barracks on the morning of the 16th announcing the fall of Singapore at 7:50 P. M. on the 15th. We had heard adverse news before, and good news, too, but that Singapore could be taken was undreamed of. This news shocked us fully as much as did the pre-internment news of the sinking of the *’Repulse” and the ‘Prince of Wales” off the Malay Peninsula by Japanese planes.

Our release was further in the future than ever, and from this momentous date one noted a changed attitude in camp. We could get no details of the Malay Peninsula debacle, and the anxiety as to what had actually happened was apparent in the drop in our morale. At about this time, too, we had many visitors; naval officers in natty white drill uniforms, Japanese civilians from Manila and the Baguio Japanese School children turned out en masse one day to see the white man behind bars. Their little faces showed no emotion as they were led the length of the barracks fence and told to take a good look at us. What a humiliating experience that was!

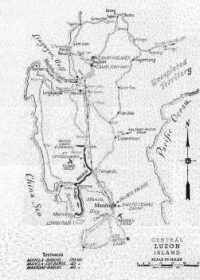

On the day of the Singapore announcement a flagpole was raised on the parade ground. Our men chopped the tree and trimmed the branches and our fellow prisoners — the Chinese — dug the posthole for it and set the pole in place. There was much rejoicing among the guards when their flag (we jestingly called it the “Fried Egg”) was hoisted; two days later there was a parade in Baguio in honor of the victory. Then came reports that MacArthur had appealed for help at Bataan and had announced that without relief he could hold out but little longer. However, rumours of our imminent release persisted; 60,000 troops had landed at Subic Bay, on the west coast of Luzon, and north of Manila it was said, and between the 18th and 22nd of the month we would be free. Yes, the 22nd would be Washington’s Birthday — an auspicious date, wasn’t it? But it was just another idle dream.

A school to permit Brent pupils to continue their studies was organized and had had a few sessions when friend Nakamura became suspicious — of what, no one knew — and all the textbooks were hustled off to Intelligence for examination. They never were returned. A request to conduct the school was denied, and in March it was decreed that there must be no study of Bible history, geography or American history as it applies to democratic

government. Months later, at Camp Holmes, the Japanese permitted a grade and high school to function.

The Manila Chapter of the American Red Cross sent a messenger to camp with four thousand pesos for the purchase of foodstuffs and drugs a supply of which was available in Baguio. The Japanese refused to allow us to accept the money on the grounds that they were quite able to attend to our wants, yet at the time, we were feeding ourselves by assessments among the internees, were almost out of money and were buying drugs on our own account for use at our hospital. We had been interned more than a year before the Japs had a change of heart and accepted remittances, through the Swiss consulate, from the International Red Cross Society headquarters at Geneva which funds originated in the United States. It was not because the money came from an enemy country that the Japs refused it but because to do so would be a reflection upon their ability to care for us. Refusing assistance at a time when we were not receiving necessary food and medicines from our “protective custodians” was inconsistent and a reflection upon the mental processes and inhumanity of the Japanese.